Ask any New Yorker about the city’s near-mythical Second Ave. subway and you’ll get an idea of how government and public works projects can stretch out over entire lifetimes. That newly opened extension of New York NY’s underground railroad was authorized in 1929, first broke ground in 1972, stalled and was restarted 35 years later, and finally saw its first trains in 2017. The fact is, government projects are the same as, yet different from, other AV systems verticals. The most apparent differences are in scale and timeline, as the Second Ave. subway amply illustrates. However, the procurement and bidding processes can be especially arcane, and the Byzantine levels of security sometimes required to insulate entire agencies from one another reflect what one observer of the process called “the native paranoia of government.”

An AVIXA overview of the government vertical from 2015 (when the organization was still known as InfoComm International) lists many of the enduring characteristics of the sector. For instance, whereas corporate and education verticals pursue cutting-edge technology, the government sector, it informs us, historically displays a preference for proven, although less advanced, technology. “When dealing with taxpayer money, fiscal responsibility is a top priority, and, so, government customers typically invest in AV technology that has been tried and tested,” it says. Similarly, although return on investment (ROI) is a front-line criterion in most AV verticals, AVIXA finds that, because government is not intended to produce profits, ROI is virtually never the most important factor to justify spending on AV technology in the government sector. Instead, it emphasizes stability, reliability and security.

Government might be a slower-moving vertical, but it’s also a substantial one. AVIXA’s latest Industry Outlook and Trends Analysis (IOTA) revealed that commercial AV revenues from the government and military vertical are predicted to grow globally to $7.1 billion in 2022, from $5.2 billion in 2017, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.6 percent. That growth will be fueled by several trends, including advances in simulation and visualization, command and control, and digital signage solutions.

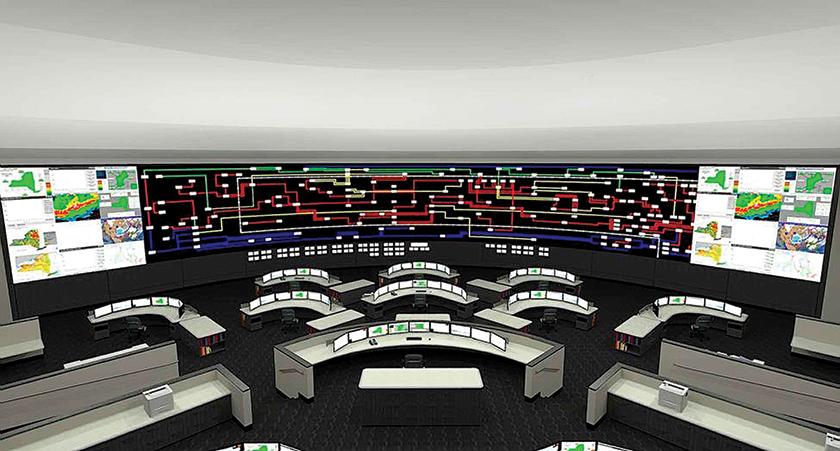

“Simulation and visualization solutions are largely driven by a need to bring operators more quickly and efficiently up to speed on increasingly complex equipment and technology,” Sean Wargo, AVIXA’s Senior Director, Market Intelligence, stated. “Command and control goes without saying, but also reflects ongoing modernization efforts of the various centers to allow for better observation, coordination and communication. Displays, lighting and AV-related IT infrastructure are all part of this.”

Security Concerns Drive AV

Recent events are accelerating the sector’s growth and, perhaps, its uptake of technology. Some AV systems integrators who have experience in the government and public works sector have seen an expansion in the market in the last year or so, driven by the need to update infrastructure. Tracie Bryant-Cravens, VP of Sales for Enterprise Accounts at AVI-SPL, said that law enforcement and security, in venues that include police command-and-control centers and network operations centers (NOCs) used by emergency services, have been benefiting, in particular, from increased federal and state grant funding.

Bryant-Cravens referenced the Texas Department of Public Safety’s NOC, which AVI-SPL built 22 years ago, and for which the company just submitted its proposal for a technology update. It was prompted, she said, by recent events, such as Hurricane Harvey, which flooded much of Houston TX last year. Florida’s state-level emergency-services response to Hurricane Irma last year is also compelling officials to look at the state’s response infrastructure. What turned out to be the most expensive US Atlantic hurricane season ever, racking up $202.6 billion in damages, will likely stimulate wider spending on emergency operations centers nationally and, thus, create demand for AV systems and services. All of that helps underscore Bryant-Cravens’ point when she said that last year was the best year ever for the company’s Control Room Group. “It was our number-two department in 2017 in terms of revenue,” she noted.

A focus on security is also making AV integrators more, well, integral to the entire governmental apparatus. “We’re being brought in much earlier than ever before on government projects—sometimes, even before the architect is hired,” she stated. “That was almost never the case before.” It’s also restructuring how monies are allocated for AV. Whereas, once, AV systems worked from a separate budget on these types of projects—a budget that, often, was an afterthought and, sometimes, was plundered by other services before AV integration was completed—AV is increasingly part of larger budget domains, such as those for the general contractor or the architect. That serves to protect those funds, she observed. “They’re now including AV into the project budget itself, not as an add on,” she added.

That, in turn, is creating closer collaboration with those architects and contractors, which oftentimes results in better use of all the funds. “We’re not just being brought in at the end, when we’d have to rip out some of the walls they’d just finished putting up,” she concluded.

Networked AV

Government AV projects are often compared to corporate ones; they just take a few years longer. Three to five years, more precisely, which mirrors the approximate terms of the extended contracts under which many AV integrators work in this highly regulated sector. More even than corporate CFOs, government fiscal watchdogs want predictability, which extended-term contracts offer. They’re also good for the integrator, whose firm benefits from a predictable revenue stream that’s often made more comfortable by the continued decrease in costs of AV technology.

What frequently makes government work more difficult than corporate work, however, is the level of bureaucracy involved. “We’ll have to balance the needs of between four and six different people versus one or two on a corporate or other type of project,” Wayne Lusthoff II, Account Executive at iSpace Environments, stated. The Minneapolis MN-area integrator has been deeply involved in Minnesota state facilities, especially courthouses, for the last half-decade. “It’s a bigger hierarchy you have to deal with,” he added.

Lusthoff believes the most significant change in the sector in recent years is the enthusiastic uptake in collaborative media in courtrooms. Attorneys are increasingly amenable to the idea of virtual corpus delecti when it comes to witnesses and evidence, and judges are able to handle much heavier caseloads when suspects can be arraigned through video portals that connect jails and courtrooms. Incidentally, it also considerably reduces transport and security costs.

Much of this has migrated to a network, with those same platforms being used over IP. Most of that video is at 1080p, and Lusthoff doesn’t expect it to jump to 4K or ultra HD anytime soon. “Neither the content nor the need are there at this point,” he opined. However, cases with critical engineering or medical testimony might change that in the future. Audio, which is increasingly being routed over IP, as well, is seeing a wide range of microphone types—ranging from ceiling-mounted arrays, to wired goosenecks and table mics, to handheld wireless (many of which are being replaced with models that avoid the 600MHz range, which was repurposed last year in the wake of a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) auction). Meanwhile, according to Lusthoff, he’s seeing the increased use of personal wireless mobile devices, especially tablets.

All this is making courtrooms and other meeting spaces in government facilities resemble corporate media environments. “It’s becoming harder to tell the two apart in many cases, because the technology in both is so similar now,” he commented. “It’s not at the point yet where people are using their smartphones in this environment like they are in business, but that’s where it’s heading.”

Design consultancy Convergent Technologies Design Group (CTDG), in the Baltimore MD area, is close to the federal government’s hub, and the firm recently did AV updates for the US Geological Survey’s offices. Bill Holaday, Principal, said personal mobile devices are making some inroads into government AV systems designs, which, he added, could be an inflection point in this traditionally staid vertical. However, there is also some pushback against that. “It’s the security issue,” he noted. “They can’t let someone who is making a presentation onto their [internal] network. That AV will have to come in through a separate network,” which, he said, creates a kind of technological “moat” around a facility’s AV culture. That keeps it from achieving true parity with other sectors.

On the other hand, there is often more at stake, when it comes to security, on a government level. Holaday cited how judges have to balance their desire to have more advanced AV systems in their courtrooms with the potential for those systems to interfere with judicial processes. “If an attorney or a witness were to inadvertently bring the wrong image or information in, because the AV system was so accessible, it could create a mistrial,” he explained. (One way to avoid that type of problem—and provide an AV-centric solution—is to design in a previewing system at the judge’s bench.)

The Changing Matrix

Although collaborative AV tools are becoming more common in government environments, they are doing so in one of AV’s most security-conscious spaces. “We’ve done projects that, literally, have 52 levels of data networks,” Steve Emspak, a Partner at consultancy Shen Milsom & Wilke, said. “At the same time, they have a hundred consoles in an operations center to be able to share in real time, with full redundancy. It’s a challenge.” But that challenge, he added, is increasingly doable, thanks to more innovative technology and products, with decreasing costs. “You can actually reconcile the ‘cheap, fast, good’ equation, because the competitiveness between manufacturers is creating great technology at affordable prices,” he observed, even as a highly consolidated AV integration service sector is able to add purchasing power, as well as more predictable labor costs. That produces another kind of challenge, he said—one in which not all integrators might be familiar with the entire range of product solutions in a fast-changing market. For that reason, Emspak noted, when his company specifies certain complex systems, it also prefers to choose the integrators, as well, to ensure that the consultant’s and agency’s visions are fully and properly integrated, particularly as government data moves onto multi-layered secure networks.

A Different Business

Government projects have historically tended to be walled gardens, available to vendors whose firms complete a circuit of often-arcane bidding and other processes across a relatively lengthy timeline, and they’ve tended to favor system reliability and security over state-of-the-art technology. However, that’s changing, as personal mobile devices and accessible software begin to transform the sector. Bruce Kaufmann, President and CEO of design/build firm Human Circuit, which once saw as much as two-thirds of its business come mostly from the federal government to its base in Washington DC, cited that dynamic, as well as a changed vendor culture around government projects, as the reason the future might not resemble the past.

“An article? Maybe you should be writing a book instead!” he quipped. Kaufmann cited the proliferation of types of procurement vehicles used by the federal government and a shift toward big contractors, such as Northrop Grumman and Boeing, which often subcontract work like AV integration themselves as part of larger bids, rather than contracting directly with the AV integrator. He also referenced the increased commoditization of AV technology and services. “The government game has become a big-player game with some niches now,” he observed, noting that government projects now account for closer to one-third of Human Circuit’s work. “That’s making less work available to smaller companies.”

Holaday agreed that government bid processes can still take considerably longer than most other types of projects; that characteristic becomes a vulnerability when it comes to AV technology, which is changing at a faster pace than ever before. To counter that, he said, CTDG will often delay providing the AV package bid component of an overall project design, while also building in terms that compel manufacturers to replace elements that become obsolete or discontinued in that time, at no additional cost. “The rapid rate of change in AV equipment is much more noticeable in government than in other AV verticals, and that can be a struggle,” he admitted. “Those are some of the ways we can keep their technology closer to the edge.”

The Future

Periodically, larger events will reshape the government narrative. The 9/11 attacks were an extreme example, but 2017’s litany of natural disasters—from hurricanes in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, to massive brushfires across California—are already having their effects. Holaday said he’s noticed that the architects and general contractors whose firms lead the agenda for government facilities contracts are moving their focus away from the broader landscape and toward those affected regions. “Normally, they might be looking at an airport in Tennessee or a healthcare facility in Pennsylvania,” he said, “but, instead, they’re focusing on public-safety projects in Florida or Houston. We haven’t seen the uptick in actual projects yet, like new emergency operations centers, but we expect it will come soon.”

Data breaches in general, and the hacks surrounding the 2016 presidential election in particular, are putting new emphasis on cyber security, Bryant-Cravens observed. That will accelerate AV/IT convergence. The good news for the AV side of that, she said, is a growing need for more advanced display and communications platforms, as well as more interaction with security resources. She cited AVI-SPL’s collaboration with InfraGard, a non-profit information-sharing and analysis partnership program between the FBI and the private sector that’s intended, according to its website, to “expedite the timely exchange of information and promote mutual learning opportunities relevant to the protection of critical infrastructure.” She explained, “We’re taking their footage and other content and putting it across multiple screens, to show them how AV can help manage it. It can get pretty ‘Minority Report’-like. And we’re already seeing some penetration of 4K and ultra HD video in fusion centers,” which are joint information-sharing facilities created under the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of Justice in the Department of Justice.

The consensus is that government AV will remain its own universe, where installations remain in place far longer than they would in other verticals, leaving it perennially a kind of time machine: In some places, CRT televisions are still mounted on large brackets and projectors shine onto bare walls. But, any of those spaces can be shot forward in time through periodic updates. And even as staid a vertical as government cannot resist the leavening effect that IT convergence and mobile-device integration are beginning to have.

Kaufmann said the sector is beginning to evolve its own CIO cohort, asserting greater control within agencies and departments, in the form of managers who can coherently guide AV and IT onto networks. It’s part of a larger process in which, he said, “AV is becoming a subset of IT. We are seeing the arrival of the government CIO, and that’s part of putting government and corporate IT in the driver’s seat for technology decisions. Government has always lagged the corporate marker, but it’s closing the gap.”