Designing AVL systems for a broadcast campus that streams audio and video to multiple other campuses can be a tricky balancing act. The integrator must make sure to create the best possible worship experience for the broadcast campus itself, while also prioritizing how the content streamed to the other campuses will look onscreen. Both of these concerns have to be front of mind in order to ensure that all the client’s needs are met.

A recent AVL installation completed by CSD Group at the Summit Church’s brand-new Capital Hills Campus in Raleigh NC offers a fine example of how to balance these two major priorities. The CSD team was tasked with designing systems for Summit’s freshly built broadcast campus that could be used to capture and stream compelling worship content for eight additional locations. (The Summit Church avoids using the term “satellite campuses.”) At the same time, worshippers in the room had to have an engaging experience, as well.

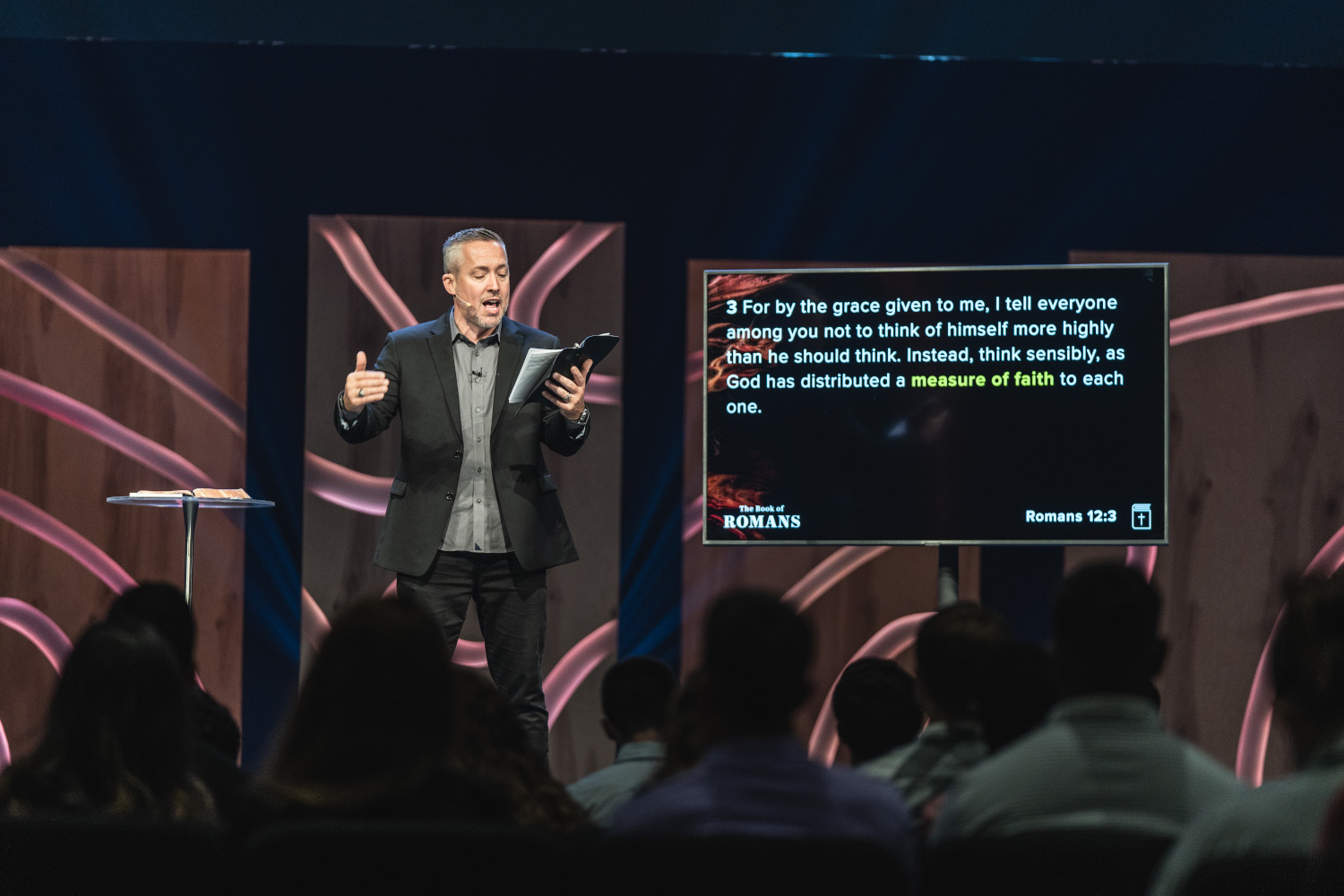

The Capital Hills broadcast campus seats 1,600 in a fan-shaped arrangement with a slight rise to the rear wall. The room is oriented toward the main stage, which features three LED walls: one in the center that serves as a backdrop for the speakers and musicians, and two on either side for image-magnification (IMAG) purposes. The building was a new construction designed by architectural firm LS3P.

According to the Summit Church’s Production Pastor, Justin Manny, the opportunity to build the new Capital Hills broadcast campus from square one gave the church the opportunity to build on what it had done in the past on the broadcast end of things, while also removing some of the complexities that arose from patchwork fixes over time. The church also wanted to take its in-venue experience to a new level—specifically in the audio department.

“We were excited to build a broadcast system from the ground up, intentionally,” Manny shared. “Our previous broadcast location was built up over time, and things were added to the system at various points. This led to challenges, like camera-sensor difference, and a general complexity that comes with adding a thing here and another thing there. With Capital Hills, we were able to take a look at our workflow and design a system that functions how we need from the ground up.” Manny highlighted some specific areas where the church wanted to take the next step forward with its in-venue production, as well as some areas where it wanted to keep things tried and true. “We are not a production-heavy church,” he shared. “Our goal is to create depth, saturation and texture with lighting. The main place where I felt we could push the envelope a little was in sound. We wanted full and high-quality sound that has even coverage and [offers] a consistent experience from the front to the back. Our expectation for the systems was that they allow the Gospel to reach people, not take And, obviously, balancing excellence and artistry with practical needs has been our focus from the beginning and all the way through the process.”

Balancing Act

That balancing act had the potential to create some challenges, but the CSD team was equal to the task. The project was led by CSD Principal Consultant David McCauley, who gave Sound & Communications an extensive breakdown of the installation. He began by describing the overarching aims of the system design, much of which involved balancing the church’s in-venue needs with its broadcast needs.

“They wanted a good concert-level audio system; that was the first call,” McCauley explained. “And then a good system for IMAG support…image-magnification support. But then, [the church wanted] a good place to do messaging onstage, as well. So, those were two different aspects [to consider]. We talked about LED screens. Lighting was a different thing because, during worship and music parts, they wanted the lighting to be more concert-like, more immersive [and] more saturated, color-wise. But then, it’s also a broadcast church, so they also needed it to be broadcast-level lighting and coverage for when a speaker came out onstage [so that] it was lit completely and evenly for broadcast. In the lighting world, that’s two different types of setups. And then they had a nice separate control space for video production, [as well as] a separate control space for audio mix-down.”

McCauley completed his summary by stating the project’s main goal, which was apparent from its earliest stages: “One of the big things going into this was that they were really trying to make sure that the room made a nice, engaging experience for the people who were in the space but also had everything that it needed to be able to drive to the other campuses.”

Services at the Capital Hills campus are typical of broadcast churches in the multi-site-church milieu. “Generally, we start the service with worship/scripture. We run through a relatively diverse catalog of songs that fit the diverse population of our church. Lighting and video elements help to create an environment conducive to worship,” Manny described. “Most services then include a time of prayer led by the campus staff. The sermon is broadcast from Capital Hills to the other eight campuses on the weekend—generally a 45-minute message, give or take. Most weekends we respond in worship following the sermon and end the service with offering and announcements.” In addition to the teaching segment being streamed to the other campuses, some services at Capital Hills are also recorded and made available for online streaming.

Audio System

Since music and spoken word are the essential elements of the in-venue worship experience, audio was the main priority for that side of the project. After much consideration, CSD specified a d&b Soundscape-based system.

At first, CSD considered a line-array system. “One of the mandates of the church was they didn’t want to feel like how sometimes when you go into a facility, the PA’s massive and you feel like you’re going to get punched in the face by this big speaker array that’s hanging in front of you,” McCauley shared. “We looked at arrays, and we looked at a couple different ways of doing them and keeping them up pretty high, because the ceiling was a little bit lower than we may have liked, if we were going to do arrays. We were really searching for a good method to make this happen, but also get the SPL they wanted and the feel they wanted.” He added, “We had looked at exploded-cluster stuff as well. Sightline-wise, that would have been great. But most of the time, an exploded cluster is mono, and if you do any kind of shading in between, that’s usually not good. So, we kept on going back to the arrays, like a nice stereo array with out-fills.”

However, McCauley already had some hands-on experience with the Soundscape system, and his appreciation for its positional-audio capabilities led him to suggest it as an option. “At the time, I had been working with d&b a little bit on their new Soundscape stuff. And I’m an old theater guy, so I’m used to more surround and locational-audio-type setups,” McCauley said. “So, we did some demos with the church, and I let them experience the arrays that we were thinking about. And they loved them. And then we did a setup with the Soundscape to show them what that does, because I’m a big proponent of positional audio. And once they experienced that, they were like, ‘Oh, that’s what we want.’” He continued, “So, that led us into, ‘OK. Well, how much is that going to cost?’ And when we did the math, because we’re using point-source speakers, delays and surrounds, we were actually able to come in pretty cost-effectively. I mean, it was a little bit more than the other system, but it was very comparable, much to our surprise and giddiness.”

The system uses a total of 44 d&b speakers: 12 24S-D, two 12S-D, two 12S, two 10SD, 24 8S and two 5S. “The mains are 24Ses. And then we have a delay ring of 24Ses. So, there’s five 24Ses up front and seven delay-ring 24Ses covering the back half of the room,” McCauley described. “Then, for surround speakers, the ones on either side of the stage are 12Ses. And then the next ones out are 10Ses. The rest of the surrounds around the room are 8Ses. And those two 5Ses are outer front fills that needed to be a little bit smaller.” He added, “Design and deployment are so key to this type system working well. If you don’t know how high to put the speaker, how to space them correctly and how to drive them correctly, the result can be not great. I think we got the placement right so that it doesn’t blow people out too bad when they’re close to the speakers, but the sound still reaches into the room deep enough that everybody gets to experience the immersion.”

A mix of d&b J-SUBs and B6es handles the low end. “We have four B6es on the floor in a specially designed [part of the stage]. And then we have three J-SUBs in the air, dead center,” McCauley said. “With wide rooms, you want to make sure that you don’t collapse the pattern of your bass. And I’m not a big fan of separating bass, especially flown, because then you get a whole lot of interaction, comb filtering and stuff.” He added, “This is not a crushing bass component. They wanted it to be musical, but they want to be able to feel it. And that’s pretty much what they have. I wouldn’t call it bass-heavy. I would just call it appropriate.”

Audio Processing

The entire audio system is driven by a d&b DS100 processing platform for Soundscape. A Yamaha RIVAGE PM7 is used for the in-house mix, and a Yamaha CL5 is used for the broadcast mix. The mains and subwoofers are powered by five d&b 30D amps, and eight d&b 10D amps power the surrounds. “Everything is driven on Dante,” McCauley said. “There are four d&b DS10 audio network bridges that break out the Dante to AES, so every amp is fed AES, and the signal never comes out of digital. Basically, the signal flow would be Dante out of the console to the DS100 processor, then from the DS100 back into Dante out to the DS10s, and then from the DS10s to the amplifiers running AES. The interesting thing is, every speaker has its own amplifier channel, so [all of them are] direct-driven separately. There wasn’t anything parallel in this system.”

According to McCauley, this is the first Soundscape 360 system installed in a church. The Soundscape system can be configured in either a 180 setup, meaning a crowd-facing speaker setup oriented around a proscenium stage, or a 360 setup, which includes surround speakers throughout the room in addition to the stage setup.

“The 180 part of it is basically locational to the stage,” McCauley described. “So, let’s say you have five speakers across the stage. Every microphone on that stage has a corresponding placement, [which is represented by] a little circle on a computer screen. You can position on your screen approximately where the microphone is on the actual stage. And then the speakers are time delayed to that particular microphone, for volume and position. It is timed so that you think that you’re actually hearing the sound from the stage, not from the PA. It’s really awesome because, positionally, everything makes sense to your brain.”

He continued, “In a 360 system with the surrounds, you can emulate different rooms. So, you can make the room sound like a cathedral, or you can make it sound like a pretty tight nightclub, or whatever you want to do. In Soundscape, the cool thing is [that] I can have somebody playing a violin and have it edged down like they’re in a cathedral. But then somebody could start speaking onstage, and [you can have him sound like he’s] not in the cathedral, even though the violin, at the same time, sounds like it’s in a cathedral.” Within the DS100 processor, Enscene software is used for the positional aspect of the design, whereas Enspace software is used for the room emulation.

Microphones used onstage include Shure ULXD transmitters equipped with KSM9 capsules. The band uses Shure PSM1000 personal in-ear monitoring systems.

Video System

On the video side of things, the choice of LED screens and their placement on the back wall of the stage were major considerations. There are three videowalls: two on either side of the stage that are used for IMAG, and a central screen that serves as a backdrop for the stage and that is used to display graphics. The screens are made up of Vanguard P4 Rhodium LED panels with four-millimeter pixel pitch. Each side screen measures 21’x7.1′ and is composed of 100 panels. The center screen measures 21’x11.8′ and is composed of 120 panels. “LED was the only real option for a seamless look and to be able to be bright enough to compete with the broadcast lighting,” McCauley said.

According to McCauley, making sure that LEDs look good on camera is a tricky proposition. So, CSD decided that the best approach for the broadcast side of the equation was to ensure that the LED screens would not be visible in the tight shots that are captured during the teaching portion of service and streamed to the other campuses.

“At one point, we did talk about going with something that would be on camera, and we would have [gone] for a lot tighter of a pitch—probably 2.5-mil or something like that. But we just decided to keep everything off camera for the tight shots,” McCauley said.

Regarding the difficulties entailed in using LED as a backdrop for filming, McCauley explained, “The problem with LED at the moment is, man, it’s the Wild West. I mean, everybody’s coming out with them. And if it’s just people looking at it, that’s one thing. That could be good or bad, depending on what brand you buy. But, as soon as that LED gets onscreen or on camera in any way, shape or form, you better do your homework is all I can say.” He emphasized that, when it comes to avoiding the moiré effect, so much depends on the camera, the lens and the distance from the talent to the wall itself, as well as ensuring that the wall has the proper electronics and pixel spacing. “There are so many things that people get into trouble with,” he lamented.

McCauley continued, “I work with some major players on this stuff, and [they tell me] this: ‘You’ve got to train your camera operators because if they hard focus the wrong way or if they slip on focus, you’re going to get moiré almost no matter what.’ And that’s with really, really, really nice cameras. It’s just one of those things that I don’t think people really understand. There’s so much bad information out there. And, of course, everybody’s trying to sell their product and everybody says, ‘Oh, I’m the best. I don’t have moiré.’ I hear that all the time.”

Instead of showing the back-wall LED screen in the streaming camera shot, during teaching segments a technician will roll out a 70-inch Samsung display on a wheeled cart, and that display is used to show on-camera visual aids for the streamed message.

The video production team uses a Ross Carbonite Black Plus 2 M/E live production switcher to produce two different video feeds: one for in-house IMAG, and one for streaming. Content is fed to the LED screens using NovaStar processing. The camera operators have four Sony HXC FB80HN studio cameras at their disposal, and three Marshall CV502 mini cameras are placed around the stage to capture shots of the musicians. Two Blackmagic HyperDeck Studio Pro 2s and six Blackmagic HyperDeck Studio 2s are used for recording purposes.

Lighting System

Another major concern for this installation was ensuring that the lighting was conducive to the in-house worship experience, while also meeting broadcast-video needs. This proved to be one of the more involved balancing acts on the project. “The interesting thing about this particular space is that it needed dual-purpose lighting, to a certain extent,” McCauley shared. “It needed to have that that very saturated, concert-y kind of look with just a touch of face light—just enough to make sure you knew what they look like—but the rest of it was solid color. They don’t do a whole lot of moving lights, but they wanted the ability to do just a touch of it.”

Highly saturated, full-color lighting was crucial to the feel the Summit Church wanted to cultivate during the musical part of service. “They wanted really deep saturation of color,” McCauley said. “For the contemporary worship side, it is very important to be able to be immersive and have that saturation. So, it was very important that the house lights be full color. What that does is basically extend the stage lights out over into the audience, so the audience feels like they’re more in the moment, like they’re a part of it, versus, ‘Oh, well, the band is saturated. We’re not.’ When the lighting extends over, they’re like, ‘Oh, wow, we’re in this with them!’ So, it’s a cool effect.” He continued, “But then the lighting had to go from that to a broadcast look, where every position could be fully lit with at least five lights hitting it and then an up-fill, or you could just do it with a center key light and all saturated color with an up-fill kicker.”

McCauley elaborated on the importance of uplighting to achieve the desired broadcast feel. “One thing that we were able to do architecturally is build in a lighting trough on the front edge of the stage. So, we were able to build in uplights, but they’re kind of hidden from the audience. That allows you to have your face light a little closer and a little higher without making people look dead, or like raccoons,” he joked. “And it gives a nice, more even wash, because it fills in the gaps between the crossovers of [the other lights], and it helps it to look more clean as somebody walks across the stage.” Making sure the uplighting provides just the right touch is its own balancing act. “Uplight used wrong is very annoying and very distracting,” McCauley warned. “If you have your uplights too strong, what you get is shadows going the opposite direction that nature intended. So, you move your hand and there’s a shadow cast up on your face. That freaks people out. The up-fill is important to a certain extent, but the key is always that your face light is dominant. Your up-light just fills in enough that your shadows are still going down.”

The lighting system includes 46 Chauvet Professional fixtures and 35 Elation LED bars. It is controlled via a GrandMA dot2 lighting console and two Chauvet Professional Net-XII Ethernet-to-DMX nodes that are used to trigger DMX presets.

The AVL system is largely run by volunteers. “I highly value volunteers, giving them the ability to serve the church in that way,” Manny said. “Not everyone is good at hanging with kids, and not everyone wants to smile at every person that comes in. I feel like production in the church is a great way for many people to use their skill sets and serve the body of Christ. So, we have three staff: one who runs sound, one who directs broadcast and one who leads the volunteers team. Other than that, it’s all volunteers. They run lights, cameras, switcher and lyrics. Some people come from production backgrounds, some are brand new.” CSD worked with its manufacturer partners to train the Summit team on the new systems.

All told, the project was a success, and it has resulted in an ongoing working relationship between CSD and the Summit Church. “We are really excited as we move into future projects to continue to work with CSD,” Manny concluded.

CSD Group Personnel

• David McCauley, Principal – Consultant/Designer

• Marty Jones, Project Manager and System Designer

• James Butler, Engineer

• Cory Hall, Sales Engineer

• Jeff Hedback, Acoustician

• Josh Buendorf, Lead Installer

• Daryl Wicker, Installer

• Scott Boroff, Installer

• Dylan Tatman, Installer

• Cody Vaught, Prebuild

• Jacob Schmell, Purchasing

• Cooper Hood, Purchasing

• Adam Henderson, Scheduling and Logistics

• Jake Drown, Integration Manager

• David Johnson, CSD Marketing and Photos

• Kim Hood, Accounting

• Cady Johnson, Accounting

• Doug Hood, Owner of CSD

The electrical contractor on the project was Triangle Electrical Service.