Philo Taylor Farnsworth (1906-1971) was born in Indian Creek, Beaver County UT, on a farm that had been settled by his paternal grandfather in 1856. Named after his grandfather, Philo was the oldest of several siblings born to Lewis and Serena Farnsworth. In the spring of 1919, the 12-year-old boy was holding the reins to one of the three wagons that topped a ridge outside of Rigby ID, where they had come to sharecrop on Philo’s uncle’s farm. He immediately noted that there were wires strung between the various buildings and he excitedly exclaimed, “This place has electricity!” Although he was experiencing electricity first-hand for the first time in his life, he would later prove that he could master the mysteries of this new force.

Quick Study

A few weeks after the Farnsworths had arrived in Rigby, the electrical generator failed. While the adults stood about wondering what to do, Philo took the machine apart, cleaned all the bearings and internal parts, gave it a light coat of oil, reassembled the balky generator and started it up again. The Farnsworth Farm’s electricity had been restored. With encouragement from his father, Philo set about building electrical motors from spare parts; he used these to power his mother’s washing machine and some of the other farm appliances.

“I realized I was tutoring perhaps the smartest student I would meet in my lifetime.”

In his spare time, Farnsworth retired to his loft in the attic of the house and read voraciously whatever books and journals about electricity his father could afford. With the turning of every page, the young Farnsworth was fascinated with the inventions that seemingly probed the depths of nature’s mysteries and how her secrets could be used to ease the burden of mankind. He confided in his father that he would become an inventor.

High School Days

In the fall of 1921, Farnsworth enrolled as a freshman in Rigby High School. He found his classes dull and boring, and cajoled his way into a senior chemistry class. Fortunately, he met a sympathetic mentor in the form of Justin Tolman, who taught the course. Tolman was to later say, “I realized I was tutoring perhaps the smartest student I would meet in my lifetime.” Tolman took the time to spend with his prodigy after school and loaned him books about advanced mathematics, chemistry and physics from his own library.

As history tells it, one cold night in January 1922, Farnsworth had finished his chores and was nestled in his attic hideaway with his books and magazines when he was captivated by an article entitled, “Pictures That Could Fly Through the Air,” which he read several times. The writer described an electronic magic carpet that, by marrying radio and motion pictures, would bring sight and sound into the home simultaneously. At age 14, the young man was convinced he had stumbled onto a problem that he and perhaps he alone would ultimately solve.

While some of the most brilliant minds of science, backed by some of the biggest corporations in the world, searched for a means to turn light into electricity, a young farm boy harrowed the endless furrows of a potato field behind a horse-drawn conveyance and daydreamed about how what we know now as “television” could become a reality. Legend has it that Farnsworth noted the long straight rows of the harrowed field and conceived of how such lines could be scanned line-by-line with a magnetically deflected electronic beam and be displayed by trapping light in an empty jar. This idea, which forms the basis of TV to this day, was crystallized in the mind of this 14-year old guiding a horse through a potato field.

Legend has it that Farnsworth noted the long straight rows of the harrowed field and conceived of how such lines could be scanned line-by-line with a magnetically deflected electronic beam and be displayed by trapping light in an empty jar.

Late one afternoon in March 1922, Tolman entered his classroom and was startled to find his young prodigy standing before a blackboard on which was chalked a number of electrical diagrams and corresponding equations. “What has this to do with chemistry?”, Tolman remarked.

“I’ve got this idea,” Farnsworth calmly replied. “I’ve got to tell you about it because you’re the only person I know who can understand it.” The boy took a deep breath. “This is my idea for electronic television.”

“Television?” Tolman asked. “What’s that?”1

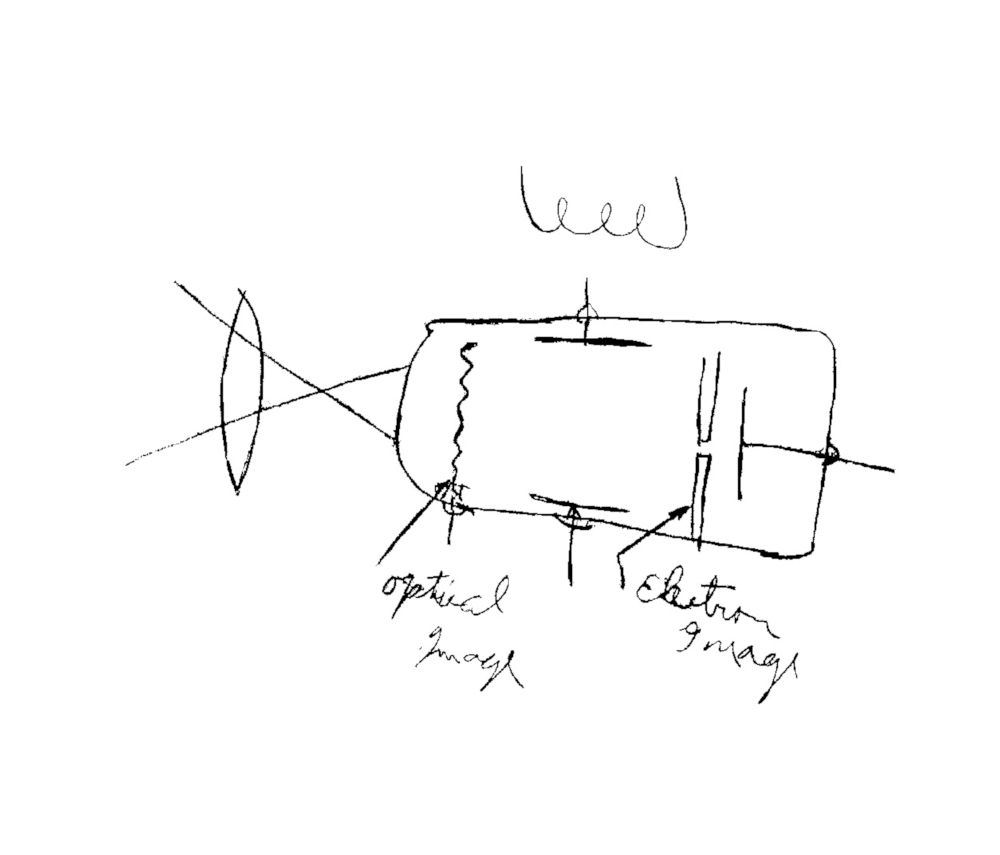

Farnsworth sketched out on paper a diagram for his concept of an electronic camera and left it in Tolman’s hands. The teacher had a premonition and saved the sketch, along with some of his young student’s notebooks. As it turned out, the information became vital evidence in later squabbles over patent rights.

More Hard Times

Hard times in 1923 forced the Farnsworth family to leave Rigby and relocate near Provo UT.

By employing the same tenacity that had served him in high school, the by-now “Phil” Farnsworth cajoled himself into Brigham Young University. This brought to him the resources of a major university, where he explored the elements of CRTs (cathode-ray tubes) and other vacuum tubes. However, the lack of financial resources stymied his efforts to construct a model of what he could clearly envision in his mind.

At the time, the Farnsworth family’s neighbor in Provo was the Gardeners, who had a pretty daughter named Elma—everyone called her Pem—who was a year younger than Phil. He was smitten, and in due time she became his wife.

The lack of financial resources stymied Farnsworth’s efforts to construct a model of what he could clearly envision in his mind.

Just before Christmas of 1923, Lewis Farnsworth contracted pneumonia. Phil was called to his father’s bedside and charged with the responsibility of taking care of the family. Naturally, that ended his studies at BYU and caused him look for work wherever he could find it. The prospects for the development of his television ideas seemed to grow ever dimmer.

Around this time, Phil, along with Pem’s older brother Cliff Gardner, subscribed to a correspondence course in radio maintenance, and in spring of 1926 they headed for Salt Lake City to set up a radio installation and repair business. Unfortunately, the business soon faltered. To make some quick money, Farnsworth thought seriously about authoring an article for one of the popular magazines concerning his ideas about television. He thought he might be able to make $100 in such a fashion. But Cliff talked him out of the idea, whereupon Farnsworth registered with the University of Utah placement service in hopes it could help him find work.

Things Start Looking Up

As fate would have it, two professional fundraisers for the Community Chest were driving from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City in a 1922 Chandler Roadster when it threw a main bearing in St. George UT. This forced the owner of the vehicle, George Everson, and his companion, Leslie Gorrell, to complete their trip by rail.

Everson and Gorrell’s customary approach to setting up a fund drive was to enlist local college students to staff the effort. Farnsworth was one of their first applicants. He quickly convinced them that his services would prove invaluable as a Survey Manager and was hired for the position. During the course of their acquaintance, Farnsworth mentioned to Everson his ideas for a new invention. “What’s your idea?” asked Gorrell. Farnsworth replied, “It’s a television system.” To which Everson, who had never heard the term, asked curiously, “Tell who?” As the conversation dragged on into the wee hours of the morning, Everson asked what amount of money Farnsworth would need to produce a working model. The youthful inventor allowed that maybe $5000 would be required; his guesstimate was considerably short of what it would eventually cost.

“What’s your idea?” asked Gorrell. Farnsworth replied, “It’s a television system.” To which Everson asked curiously, “Tell who?”

Nevertheless, Everson pledged to provide $6000 of his own money with no strings attached—well, at least not many. An association was struck, with Farnsworth holding 50% and the other 50% split evenly between Everson and Gorrell. The one condition was that Farnsworth would have to relocate to Los Angeles. Phil and Pem, the young engaged couple, could not reconcile with the idea of being separated, and the wedding date was set. It was off to Provo in Everson’s Chandler, which had been repaired and delivered to Salt Lake City, for the marriage ceremony before a Mormon Bishop. Shortly thereafter, the young couple boarded a Pullman train and headed for Los Angeles. Their honeymoon consisted of a stroll down the beach in Santa Monica one afternoon. Then they busied themselves with the housekeeping of their one-bedroom apartment in Hollywood, which included setting up an electronics lab in the dining room.

Started From Scratch

The young Farnsworth faced a difficult task. Before he could build his invention, it was necessary to design and build many of the tools and fixtures that would allow him to proceed. It was not like he could run out to the nearest electronic parts store; rather, everything had to be built from scratch. In the process, he acquired a whole new education in such things as electrochemistry, radio electronics and the ancient art of glass blowing. (Glass blowers that he contacted told him the tube he wanted would be impossible to make. But, in typical Farnsworth fashion, he ignored their advice and proceeded to do on his own what had to be done to complete his project.)

“If you have what you think you have, you’ve got the world by the tail.”

Everson quickly realized that the initial estimate of $5000 was way off the mark and concluded that more capital would have to be raised. Before sticking his neck out further and damaging his reputation in the financial community, he called on the advice of a local patent attorney. After hearing Everson’s description of the project, the attorney was reported to have said, “If you have what you think you have, you’ve got the world by the tail. If not, then the sooner you find out, the better.”2

A Dr. Mott Smith of Cal Tech was called in to judge the technical soundness of the idea. After several hours of discussions, Dr. Smith acknowledged that the idea was technically sound and, although some difficulties would certainly arise, the project was definitely feasible. That was good enough for Everson, and he set out diligently to raise additional capital. So, while Phil, Pem and Les Gorrell scrounged for parts, Everson scrounged for money.

Crocker Bank Connection

In his quest for capital, Everson attempted to approach, Jess McCargar, a longstanding acquaintance at the Crocker Bank in San Francisco. He was disappointed to learn that McCargar was on an extended vacation; however, another banker with a reputation of being ultra-conservative—and a hard-nose, to boot—took the time to hear Everson out. This initial contact resulted in Farnsworth being summoned to San Francisco to make his presentation.

After a thorough grilling by the bank officials and their own technical experts, Farnsworth was given a backing of $25,000 and the use of a bank-owned loft at 202 Green Street. It was here that television would be born. Roy Bishop, who had headed up the bank’s contingency, was said to have remarked on the unusual event, “Young man, you are the first person who has ever gotten anything out of this boardroom without putting up something in return.”

Farnsworth was given a backing of $25,000 and the use of a bank-owned loft at 202 Green Street. It was here that television would be born.

The Farnsworths loaded their meager belongings and Phil’s lab items into Everson’s Chandler and relocated to the Bay Area. Cliff Gardner was contacted and left his job in a box-cutting factory in Oregon to join the fledging enterprise as chief glass blower. Never mind that his sole qualifications were a high-school diploma, a boldness comparable to his brother in-law and absolutely no previous knowledge of the subject.

Birth Of The Information Age

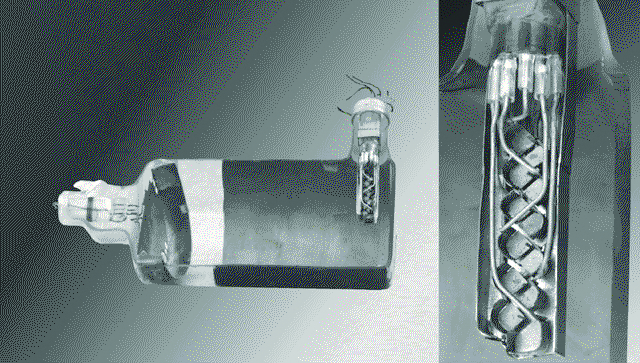

By January 7, 1927, Farnsworth had finalized his plans and drawings, and filed for his first patent. To the extent that these documents described a workable invention, this became the official date that television was invented. However, the patent could not be officially granted until a working model was delivered—and that was still a long way off. After several months of practice, Cliff Gardner became semi-proficient in his new career as a glass blower and began turning out the world’s first electronic camera tubes. Farnsworth dubbed the device an “Image Dissector” because it would transmit an image by dissecting it into individual elements and convert the elements, one line at a time, into a pulsating electrical current.

As seen in the accompanying photo, the device included an integrated photo multiplier, used as an electron multiplier in this case. The photo-cathode is at the left, the positively charged anode on the right. The optical image actually passed through the positively charged anode mesh and past the multiplier assembly to get to the photo-cathode.

After conversion on the photo-cathode to an electrical image, it was then attracted back to the anode. The deflection magnets moved (scanned) the entire image, intact, across the aperture of the multiplier. As the magnetic field was varied horizontally and vertically, the raster of lines resulted from the image, passing the multiplier aperture.

For the receiver element, a standard Erlenmeyer flask, familiar to high-school chemistry students, whose flat bottom was coated with cesium, became the first “picture tube,” dubbed the “Image Oscillite” by Farnsworth.

By January 7, 1927, Farnsworth had finalized his plans and drawings, and filed for his first patent. This became the official date that television was invented.

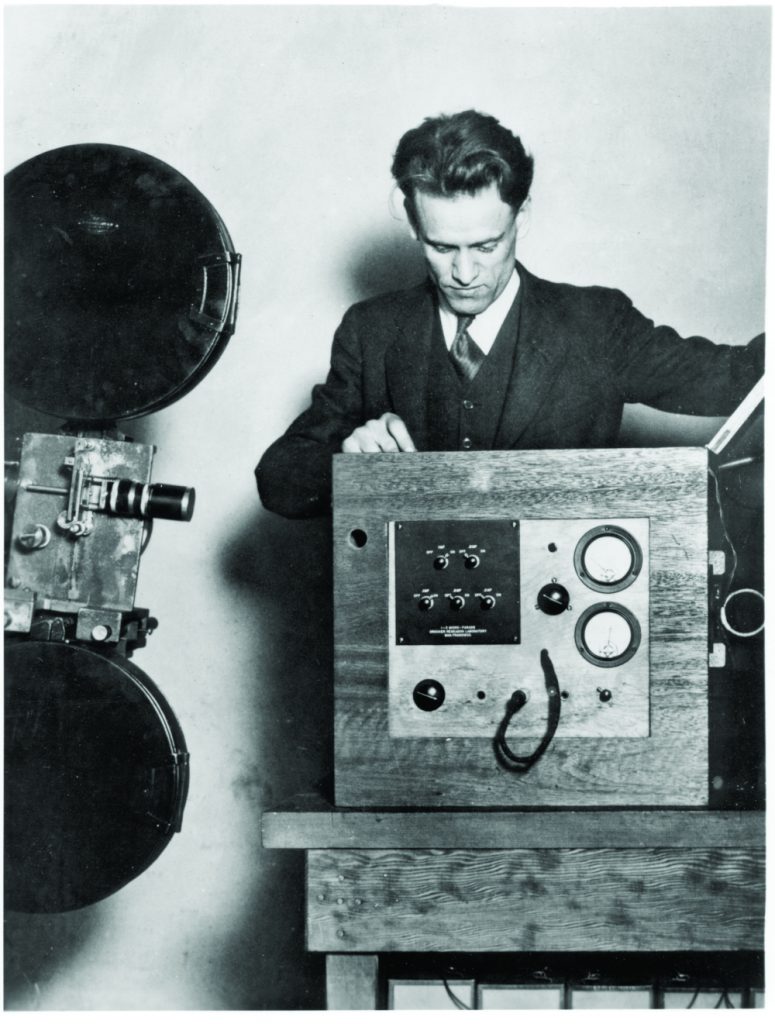

After several months of testing, redesigning and refining the system, Phil felt confident enough that, on September 7, 1927, he invited Pem and George Everson to view his first “transmission.” The test consisted of a thick black line painted on a sheet of glass. He reasoned that, if he could tell by looking at the receiver whether the line was horizontal or vertical, he could be certain that he was looking at a transmitted image. Cliff dropped the glass slide between a carbon arc lamp and the Image Dissector, and in another room the small audience observed the line on the receiver tube. Cliff rotated the slide and the image appeared as a vertical line. The information age was born. Farnsworth noted in his lab journal, “The received line picture was evident this time.” Everson was more enthusiastic and wired Les Gorrell in Los Angeles, “The damned thing works.”3

Capitalism Enters

For the remainder of 1927 and on into the spring of 1928, further refinements came out of the lab on Green Street. The staff expanded, and expenses escalated. Up to this time, the bankers had nothing other than Everson’s accounts to gauge the project’s progress. They began demanding that a demonstration be held that would allow the investors to see for themselves what was going on behind closed doors at 202 Green Street. Farnsworth pleaded for more time to perfect his work; but the investors were adamant.

Bishop observed that it would take a pile of money higher than Telegraph Hill to continue the venture, and that consideration should be given to selling the invention to “one of the big electrical companies.” Farnsworth had other ideas.

In May of 1928, the Crocker Group assembled for the demonstration. Farnsworth whispered to Everson, “Here’s something a banker will understand,” as he flashed an image of a dollar sign on the screen. A screening of various geometrical shapes and the kinetic patterns of cigarette smoke followed. The demo was a success, and Roy Bishop congratulated the youthful inventor warmly.

However, Bishop proposed an idea that Farnsworth found very disturbing. He [Bishop] observed that it would take a pile of money higher than Telegraph Hill to continue the venture, and that consideration should be given to selling the invention to “one of the big electrical companies.” It was certainly not an unlikely position from an investment banker’s standpoint. By selling, they could immediately recoup their investment and undoubtedly make a hefty profit.

Other Ideas

Farnsworth had other ideas. By his reasoning, as they perfected the invention of television, additional patents would inevitably follow until their portfolio of patents would mean that anyone attempting to enter the television market would be forced to pay royalties to their enterprise. He was also of the opinion that the toll from patent licenses would vastly outstrip what could be realized from an immediate sale. Besides, it would guard against his having to compromise the independence that he so jealously guarded.

The motion toward an immediate sale was thwarted—at least temporarily.

In 1929, a fire at the lab and the unceremonious suspension of funding forced Farnsworth to reluctantly lay off some of his prized employees. When the financial smoke cleared, George Everson and Jess McCargar, the banker who had been Everson’s initial contact at the Crocker Bank and who was no longer with Crocker, had succeeded in buying out the Crocker Group. The enterprise was reincorporated as Television Laboratories, Inc., with McCargar as president and CEO. Everson was named treasurer and Farnsworth, who still held substantial shares in the venture, was appointed director of research.

The Specter Of RCA

The spreading news of Farnsworth’s invention quickly came to the attention of David Sarnoff, vice president and general manager of the vast Radio Corporation of America. From his lofty offices atop Rockefeller Center in New York City, Sarnoff was determined to find out what was going on in that loft in San Francisco. His intentions were not in the least benevolent.

Faced with the prospects of expiring patents on radio that RCA had scooped up by buying out or legally strangling any number of free-enterprise concerns, Sarnoff was groping for a way to supplement RCA’s stranglehold on the radio and broadcast market. Visionary that he was, Sarnoff saw the upcoming future in television. He decided that the sire of television should be none other than RCA. As RCA’s manager of patent portfolios in the 1920s, he had quashed any number of lesser foes and ensured that to manufacture or sell a radio in the United States meant paying royalties to RCA. He envisioned a similar scenario shaping up with regard to Farnsworth and his upstart television venture.

If you think RCA invented television, you’d be wrong. Farnsworth battled RCA for the patent rights to TV and eventually won.

In 1930, Sarnoff became aware of the work of Vladimir K. Zworykin, who had some background in television. In fact, while working for Westinghouse as a researcher, he had filed for a patent for an electronic television system in 1923. However, the patent was never granted; Westinghouse saw little promise in the work, and the project was aborted. Sarnoff approached Zworykin with a promise to allow him to continue his research in television at RCA’s well-equipped labs in Camden NJ.

An ‘Industrial Espionage’ First

Before Zworykin reported to Camden to assume his new position, Sarnoff instructed him to travel to San Francisco to see if this upstart had invented anything that would benefit RCA. He was also told to approach Farnsworth in the guise of an engineer for Westinghouse with an interest in exploring licensing arrangements. He was also expressly forbidden to discuss his impending relationships with RCA. Sarnoff is quoted by several sources as having expressed the company tenet that, “RCA doesn’t pay patent royalties, we collect them.”

Zworykin was greeted hospitably by Farnsworth and his staff, and was essentially given free run of the Green Street lab during his three-day visit. Farnsworth discussed openly the intricacies of his Image Dissector. Zworykin was duly impressed with what he saw and conceded before several witnesses that “This is a beautiful instrument. I wished I’d invented it.”4 However, as his visit wound down, Zworykin became withdrawn and evasive concerning any patent license agreements. Farnsworth was to comment to his wife that perhaps he had revealed too much.

If Zworykin’s visit was perplexing, it was shortly followed by a request by Sarnoff himself to visit the little lab in San Francisco. Farnsworth was out of town at the time of Sarnoff’s visit, and the head of RCA was greeted by Everson. With his snooping completed, Sarnoff drew Everson aside and offered him the insulting sum of $100,000 for the entire enterprise. Without hesitation Everson declared with probably more politeness than was warranted that such a deal would be impossible. “Well then,” Sarnoff was said to respond, “there is nothing here we’ll need.” He departed quickly before Everson could ask him why he was willing to pay $100,000 for nothing.

The Philco Connection

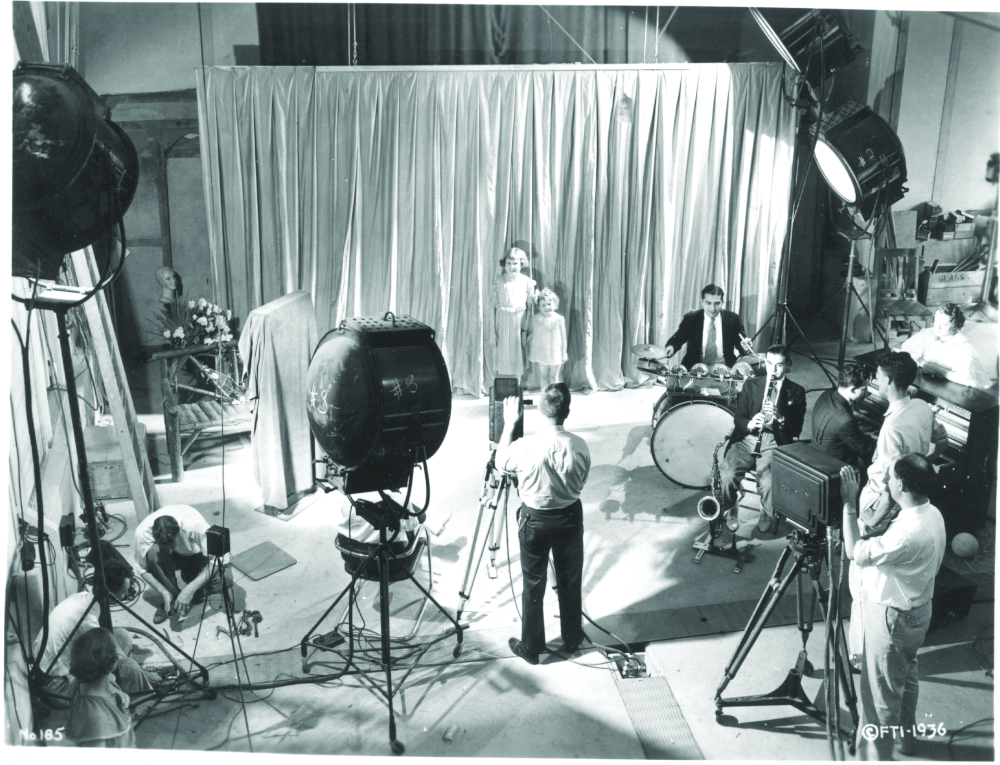

In 1931, Television Laboratories, Inc., inked a licensing agreement with Philco Radio Corporation. Farnsworth moved to Philadelphia PA for what he thought would be a six-month term during which he would get Philco into the television business. Two years later, with an ever-growing patent portfolio, Farnsworth was still on Philco property. During that time, he obtained an experimental license from the FCC to conduct over-the-air transmissions. He set up a prototype receiver in his home, and his son, young Philo III, became a charter member of the television generation as the Disney cartoon “Steamboat Willie” was screened over and over again through the film chain at the Philco Labs and into Farnsworth’s home.

Although this setup didn’t look like a television camera as we now envision them, from a technical standpoint it was. Because all of the moving images archived in this period were movies, a device that could convert motion pictures to television images was a high priority.

Farnsworth’s son, Philo III, became a charter member of the television generation as the Disney cartoon “Steamboat Willie” was screened over and over again through the film chain at the Philco Labs and into Farnsworth’s home.

Eventually, Farnsworth and his workers grew increasingly stifled by the Philco management and, much to the outrage of McCargar, Farnsworth and his group vacated their offices at Philco. McCargar and Everson hightailed it to Philadelphia in an attempt to settle this latest crisis. Farnsworth stated that he intended to stay on the East Coast to be, as he put it, closer to the action. McCargar was equally as adamant in demanding that Farnsworth cut his staff. The venture was again reincorporated, this time as Farnsworth Television, and was moved to 127 East Mermaid Lane in a suburb of Philadelphia.

The advancements worked out at Philco included the sawtooth wave, a horizontal blanking action that eliminated blur and ghosting. This was introduced, and improvements in deflection coils raised the scan rate to 220 lines per frame. Even the cabinetry had reached a point of sophistication that suggested commercialization was just around the corner. Meanwhile, the Farnsworth patent portfolio grew.

RCA Hadn’t Gone Away

In 1934, RCA began demonstrating its own electronic television system that Zworykin had cobbled together some three years after his visit to 202 Green Street. RCA also had the audacity to claim that Zworykin’s unpatented 1923 camera tube, which it dubbed the “Iconoscope,” was a predecessor to Farnsworth’s Image Dissector, and that Farnsworth was infringing on Zworykin’s priority. Thus, the opening legal salvo was fired that clearly demonstrated that the giant RCA had full intentions of crushing little Farnsworth Television, as it had done to so many other enterprises in the previous decade.

Through an unwritten edict and in an obvious subterfuge, RCA also informed the holders of RCA licenses (which included most of the radio manufacturers in the United States) that doing business with Farnsworth would result in an immediate revocation of their RCA licenses. There weren’t too many such licensees who could afford to give up their livelihoods by standing up to RCA. Sarnoff was determined to extend his empire and go down in history as the man who gave television to the world.

After a long, drawn-out legal procedure, the US Patent Office ruled in April 1934 that the priority of invention be awarded to Philo T. Farnsworth.

The Farnsworth interests took about the only step they could under these circumstances by filing a challenge with the US Patent Office. Sarnoff accepted the challenge with the full confidence that “the Radio Corporation’s battalions of lawyers would simply overwhelm this latest foe to RCA dominance over the broadcast industry.” When Farnsworth alluded to his work while he was still a young boy in high school, RCA’s attorneys met this with derision and claimed it was unthinkable that a mere boy of 14 could possibly have dreamt up anything as intricate as electronic television. They found themselves laughing out of the other side of their mouths when Farnsworth’s attorney produced the original sketches that Farnsworth’s teacher, Justin Tolman, had kept over the years.

After a long, drawn-out legal procedure, the US Patent Office ruled in April 1934 that the priority of invention be awarded to Philo T. Farnsworth. However, they gave RCA 16 months to appeal. True to their nefarious manner, RCA waited until the last day to file their appeal.

International Commerce Pays Off

During the summer of 1934, Farnsworth was invited by the prestigious Franklin Institute of Philadelphia to display his television to the public. The event was a tremendous success. It also attracted a number of foreign visitors. The status of television in England was of primary interest. State-owned BBC had been broadcasting experimental TV using the Scottish inventor John Logie Baird’s mechanical process. Baird’s enterprise was absorbed by the large holding company of British Gaumont. Both BBC and Gaumont were dissatisfied with the quality of Baird’s apparatus and urged him to seek a license for a complete electronic television system. Farnsworth’s endeavors were of particular interest.

British Gaumont signed a licensing agreement, and Farnsworth sailed home with a down payment of $25,000 in his pocket. Unfortunately, the bulk of the money went to pay legal fees, with little left for further research.

As long as Farnsworth’s patents were under contention by RCA, he could not license or sell any intellectual property in the United States, which meant he was stymied in raising money for his legal defenses—a fact that did not go unnoticed by RCA. They pursued legal action designed to financially strangle Farnsworth, much as they had done to FM-radio’s Edwin Armstrong (see “Industry Pioneers #6: Edwin Howard Armstrong: Developer Of Practical Radio Broadcasting”).

A European market offer promised a way to break the logjam and develop some funds to continue fighting RCA. To make a long story short, the demos in Britain proved successful. British Gaumont signed a licensing agreement, and Farnsworth sailed home with a down payment of $25,000 in his pocket. Unfortunately, the bulk of the money went to pay legal fees, with little left for further research.

A Venture Into Broadcasting

Farnsworth was convinced that the field of television broadcasting was the most profitable avenue to pursue. When his board of directors nixed the idea, he struck out with his own money to build and equip a TV studio in Philadelphia. The new equipment was capable of transmitting at 441 lines per frame, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued an experimental license using the call letters W3XPF. Of course, there were few receivers in the Philadelphia area capable of capturing the new signals. But, much as in the early days of radio, clever enthusiasts built their own receivers. In the previous 10 years, Farnsworth and his staff had invented TV, overcome a host of adversities and now stood at the threshold of commercial TV broadcasting.

Following a trip to Europe in 1937, during which Farnsworth vainly attempted to support his sole licensee Baird in a contentious bid for the BBC business, he returned home to learn that, in his absence, McCargar had taken steps to undermine the operation. At one point, McCargar had even voiced the blasphemy that perhaps it would be best if Farnsworth Television be sold to RCA for whatever terms could be arranged. At one point, McCargar, after a heated argument with Farnsworth, took the unprecedented action of firing the entire staff. When Farnsworth attempted to contact them—many of whom had been with the company since the San Francisco days—they refused to return unless McCargar was gone. McCargar’s interests were quietly satisfied, and his participation in the company was terminated.

Everson turned to Wall Street, and in particular the investment firm of Kuhn, Loeb, to raise equity capital. The investment bankers and their hand-picked board of directors were committed to pursuing a conservative and predictable approach to ensure the company’s profitability. Despite Farnsworth’s every attempt to sway the board, they steadfastly held by their decision to acquire a factory and engage in the manufacturing of radios until such time as the television market materialized and the pending litigation with RCA was finished.

The newly formed FCC had yet to establish universal standards for TV broadcasting and assign spectrum space for the new entity. And, until these new rules and regulations were formulated, the industry could not go forward. The FCC, with a realization that any decisions would shape the fate of the industry for decades to come, approached their task with due deliberation and time-consuming investigations.

In a surprise development, Farnsworth and AT&T inked a cross-licensing agreement of their own. The arrangement would permit the consortium to enter the TV broadcast market—and tell RCA to take a flying leap.

For many years, there had existed a cross-licensing arrangement between RCA and AT&T. They agreed to share patents as long as RCA stayed out of the telephone and telegraph business, and AT&T likewise shunned any interest in the field of radio. However, these agreements covered audio transmission only; on the subject of television, the agreements were silent.

TV Was Up For Grabs

Hence, TV was up for grabs. The only thing that stood in the way of Sarnoff’s dream of an ethereal empire was Philo T. Farnsworth. In a surprise development, Farnsworth and AT&T inked a cross-licensing agreement of their own. At that point, the AT&T/Farnsworth arrangement would permit the consortium to enter the TV broadcast market—and tell RCA to take a flying leap.

But RCA had one more trick up its sleeve. Camden announced they had perfected a new camera tube that legal claimed was original to RCA, and the marketing department quickly dubbed it the Image Orthicon. Any further work on Zworykin’s Iconoscope was sent to the dust bin. Sarnoff announced RCA would launch commercial television at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. His bombastic announcement was torpedoed when it was disclosed that Farnsworth had filed patents on the important features of the Image Orthicon in 1933—fully four years before RCA’s whiz-kids in Camden. RCA filed a challenge with the Patent Office and, as with so many prior actions, RCA lost and priority was assigned to Philo T. Farnsworth. Hence, after 15 years of litigation, in early 1938, RCA and Farnsworth’s attorneys sat down to negotiate a cross-licensing agreement.

Sarnoff was able to make good on his promise to introduce commercial television at the New York World’s Fair, albeit with devices manufactured under license from Farnsworth.

In typical fashion, RCA sought to negotiate a lump-sum settlement, with perhaps a stipend payment for future royalties. Farnsworth’s attorneys would have none of that idea and demanded an ongoing royalty settlement. Obviously, Farnsworth had the upper hand, and RCA was forced to capitulate.

Sarnoff was able to make good on his promise to introduce commercial television at the New York World’s Fair, albeit with devices manufactured under license from Farnsworth. But RCA’s public-relations department started beating the drum of propaganda that Sarnoff and RCA were the guiding force behind television….

Conclusion

Farnsworth had been battling for his ideas for 20 years. By now, he was exhausted and not too interested in what the future might bring for his invention. His retreat in the Maine woods burned, along with most of his equipment and journals, and he became acutely depressed. He suffered a debilitating bout with alcoholism as he watched the Capehart Plant in Ft. Wayne fall on hard times and as the company was subsequently sold to International Telephone & Telegraph (IT&T) in 1949. He moved back to Utah with Pem and buried himself in research in the field of nuclear fusion until his death in 1971. (For those interested in Farnsworth’s work in nuclear fusion, refer to Schatzkin’s works listed below for a detailed explanation of this phase of Farnsworth’s contribution to advanced physics.)

Today, most people are unaware of Farnsworth’s contributions to what we now consider an essential element of our communication-oriented world.

Endnotes:

1 Schatzkin, Paul; The Farnsworth Chronicles, www.farnovision.com/chronicles/tfc-part02.html

2 Ibid

3 Schatzkin, Paul; The Boy who Invented Television

4 Schatzkin, Paul; The Farnsworth Chronicles

Further Suggested Reading:

Abramson, Albert; The History of Television 1884-1941

Farnsworth, Elma G; Distant Vision: Romance and Discovery on an Invisible Frontier

Schatzkin, Paul; The Boy who Invented Television

This article was originally published in the November 2003 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.