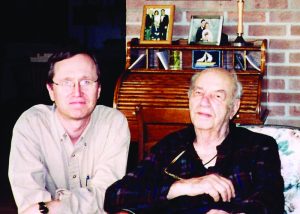

The exploits of Albert Kahn offer a compelling story of American entrepreneurship. Sound & Communications was invited to meet with the now 97-year-old to gain insight into his view of the industry’s history. [Editor’s note: This story was originally published in March 2004.]

Kahn’s Early Life

Albert Kahn was born in LaSalle IL on July 9, 1906, the only son of Maurice and Dora Kahn. His one sibling, Dorothea, a doting big sister, was 10 years his senior and later, for years, was a member of the editorial staff of the Christian Science Monitor.

In 1912, Kahn’s family moved to South Bend IN. Kahn soon linked up with three friends who shared his interest in radio. The boys all loved to tinker with radios and scrounged what parts were available from the local junkyard to build them—Kahn remembers that the spark coils from old cars could be had for about 50 cents. Almost every night, the four youngsters would gab by means of Morse code with each other over their hand-built radio sets. Kahn also remembers immersing himself in periodicals and books—anything that pertained to radio and electronics.

Amateur Radio License

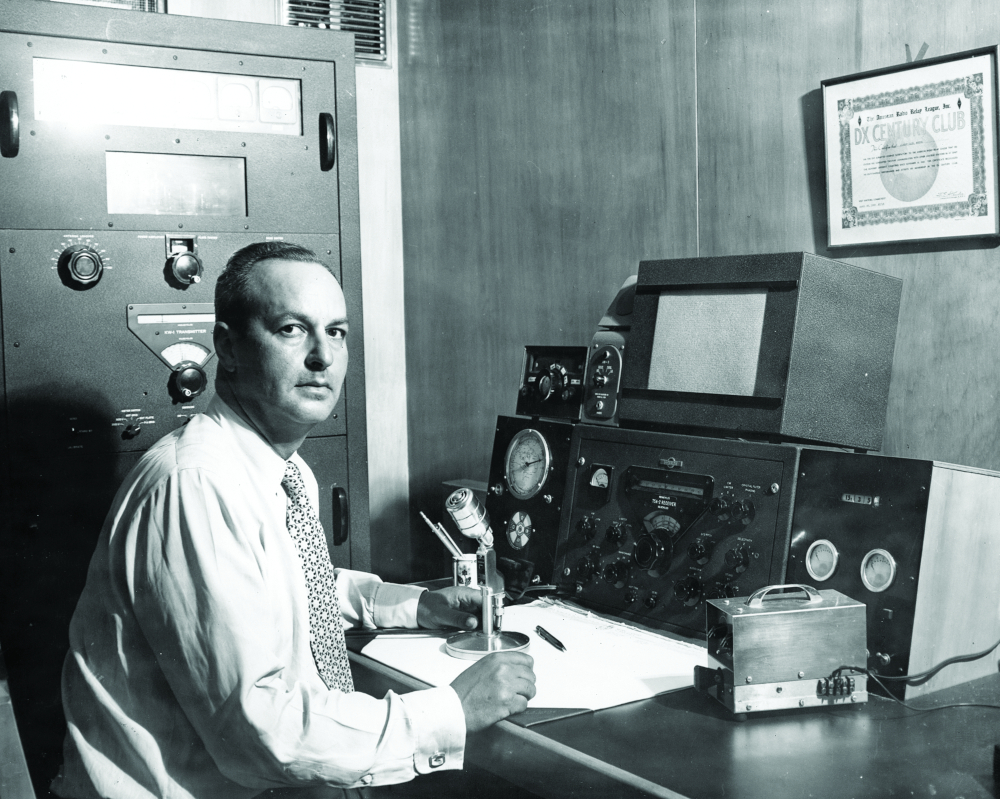

In 1921, the young radio operators learned that henceforth they would need licenses as radio amateurs. Because they lived more than 100 miles from Chicago, where the regional examinations were administered, they were allowed to give each other the necessary tests. “Naturally, we all passed.” said Kahn. Thus, at age 15, the young Al was issued his first amateur radio license, and he went legally on the air with call 9BBI.

At age 15, Kahn was issued his first amateur radio license.

Reminiscing about his earlier years, Kahn told this reporter that his home environment was “gracious and learned,” and he described his childhood as being happy and rather uneventful—“except for my unbridled interest in radio.” He further remarked that, “Beyond high school, I had little formal education. However, I did have an excellent high school education at a time when a high school graduate probably had a more grounded learning experience than that of the BS graduate from college these days. I also have always read with a great deal of zeal. In that respect, my father was a great influence. He came from a family of journalists and college graduates, and was a dedicated reader, reading and rereading all of Dickens, Thackery and many of the other classics. He got me into reading them, too.”

What Was to Come

Along the way, the young Kahn became acquainted with another man about his same age named Lou Burroughs. Burroughs had been working in a machine shop in South Bend and was a reasonably well versed machinist as well as a fellow radio experimenter. Kahn and Burroughs struck up a friendship that endured off and on for close to 60 years.

Kahn and Burroughs formed a partnership engaged in the installation and repair of radio receivers. The fledgling Radio Engineering Company opened shop in the basement of a gasoline station and retail tire operation.

The two young men formed a partnership engaged in the installation and repair of radio receivers. Their partnership was formalized on September 1, 1927, with total assets of $30 and a second-hand car. The fledgling Radio Engineering Company opened shop in the basement of a gasoline station and retail tire operation called the Century Tire & Rubber Company in downtown South Bend.

The new enterprise was largely successful initially, and soon grew to be the premier radio service shop in the area. Struck with success, they ventured into the retailing aspects of the radio business and moved into more suitable quarters. Then the Great Depression hit. Kahn related, “The depression all but wiped us out. We found ourselves insolvent to the extent of $5000. To survive and pay our creditors, we began the solicitation of work in the audio field and liquidated the remnants of our radio service and retail business.”

Kahn and Burroughs were contracted to design and install a portable PA system that Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne used to oversee his team’s practice efforts. Rockne was delighted and dubbed the system his “electric voice.” Kahn liked the name, but changed it slightly.

As a first ever, the company delivered a portable public-address system to Notre Dame University for use by the legendary football coach Knute Rockne. As the well-known story relates, Rockne was recovering from an illness that made it difficult for him to supervise his four squads of players on four different practice fields. Kahn and Burroughs were contracted to design and install a portable PA system on the tower that Rockne used to oversee his team’s practice efforts. Equipped with four speakers, a preamp, a microphone and a series of switches, Rockne could now bark out instructions to his players. He was delighted and dubbed the system his “electric voice.”

Kahn liked the name, but changed it slightly. So it was that, on July 1, 1930, the company was incorporated as Electro-Voice.

Mic Development

Most of the microphones of the day were carbon button devices, and much like Georg Neumann had learned in Germany [see “Georg Neumann: Microphone Pioneer”], carbon button microphones were of poor quality. Also, manufacturing and distribution of microphones in the US was largely in the hands of Western Electric, which was loath to sell equipment to anyone other than its established licensees.

Kahn and Burroughs worked to advance the velocity [ribbon] concept. They invested in a lathe and a drill press and started turning out microphones at the rate of about one a week.

The fledgling, little Electro-Voice Company, which was comprised of Kahn and Burroughs, sensed an opportunity. Whereas Neumann had steered toward the development of electrostatic [condenser] units, Kahn and Burroughs worked to advance the velocity [ribbon] concept. They invested in a lathe and a drill press and started turning out microphones at the rate of about one a week.

As the 1930s progressed, carbon button microphones were being replaced rapidly by the velocity microphone, in which a thin aluminum ribbon was suspended between two magnetic pole pieces. The ribbon was connected through a transformer to a suitable amplifier. One of the drawbacks of the velocity microphones of the time was their susceptibility to hum pickup. Consequently, the utility of the velocity microphone was limited despite its superior reproduction.

RCA designs overcame the problem with stronger magnets and heavy shielding, but this increased the cost, so the RCA units were not used widely for public address systems. The guilty component was the step-up transformer that consisted of a single winding and a high permeability core. Kahn came to the conclusion that the answer lay in the development of a humbucking transformer, in which the transformer secondary was in two sections and the windings opposed; any extraneous induced hum would be cancelled.

One of the drawbacks of the velocity microphones of the time was their susceptibility to hum pickup. Kahn came to the conclusion that the answer lay in the development of a humbucking transformer.

After considerable experimentation, Kahn came up with what he considered a satisfactory solution. Inasmuch as there was no commercial supplier for the “L” laminations required for the Kahn transformer, a homemade die punched them out in the Electro-Voice shop. The hum-free velocity microphone became a reality and went on to rack up record sales.

Economic Recovery

As the depression dragged on, Burroughs became disheartened and decided to withdraw from the company. Kahn assumed his obligations and stock, and struggled on. By 1933, all the debts of the prior defunct company had been satisfied, and the Electro-Voice Company (EV) was essentially debt-free. Earnings began to grow to the point that, by 1936, EV had 20 employees and was turning out a range of dynamic and velocity microphones.

In 1936, Burroughs returned to the company in the role of chief engineer. Electro-Voice was becoming a recognized force in the microphone industry. The company also started enjoying a considerable amount of OEM (original equipment manufacturing) business—private label, if you will—and Webster Electric Company of Racine WI became a prime customer. By the end of World War II, EV had successfully penetrated the lucrative broadcast market and was selling to all of the networks except NBC, which, of course, was controlled by RCA.

World War II Era

In 1938, Kahn learned that the Lansing Manufacturing Company in Hollywood was on the block. When he called to inquire, he reached Howard Souther. Souther allowed that Kahn didn’t need the Lansing Manufacturing business per se, but that he would benefit from Souther’s services. A deal was struck, and Souther joined EV. (The Lansing Manufacturing Company subsequently was acquired by Altec, but that is a whole other story.) With this move, Kahn began moving toward the development and production of loudspeakers. However, World War II intervened, and those plans were put on the back-burner.

“In the months preceding the US entry into the war, we commenced serious work to develop a noise-canceling microphone that we felt could be used by our armed forces.”

With the likelihood of the United States being drawn into the war, the US military sensed that radio voice communication systems would prove invaluable. Reportedly, using then-available technology, the percentage of successful transmission was a scant 20%. Kahn related, “In the months preceding the US entry into the war, we [Kahn and Burroughs] commenced serious work to develop a noise-canceling microphone that we felt could be used by our armed forces. After a period of investigation, we found a rather simple solution: a carbon microphone that would be placed on the upper lip of the talker, suspended by ear straps. An orifice of the correct size in the rear of the assembly was all that was needed. The simple theory was to have the offending noise enter both the front and back simultaneously, thereby canceling the noise and allowing the speaker’s voice to dominate.”

The design, dubbed the T45, in essence used a 180-degree phase shift to differentiate between background noise and the impressed human voice, thus raising the transmission success to some 90%.

Samples were delivered to Fort Monmouth and Wright Field, and also Cruft Laboratories at Harvard, which, under the direction of Dr. Leo Beranek, was evaluating communications apparatus for the government’s war efforts. The Army Air Force gave the device short shrift.

As Kahn laughingly remarked, “We didn’t get much of a reception from the Air Force: They looked at it superficially, and perhaps because it was too radical, they dismissed us.” Cruft Labs tested the unit and gave it high marks but, according to Beranek, Cruft’s staff was preoccupied with development of devices for use in high-altitude environments. And, while the Cruft Report was widely circulated, it did not catch the attention of the Air Force until late in the war.

“I received a call from a Marine Corps procurement officer. When the question of official approvals, type numbers and specification data was raised, the colonel stated, ‘Forget all about that: When can you get us 100,000 pieces?’”

Kahn realized that if the Army Air Corps wasn’t interested, perhaps the Army Tank Corps would be: “So off we trooped to Fort Knox,” he said. The reception from the Tank Corps was more promising, and the demonstrations caught the attention of the Marine Corps, which was seeking noise-canceling microphones for use on its amphibious landing crafts. As Kahn related, “Shortly thereafter, I received a call from a Marine Corps procurement officer. When the question of official approvals, type numbers and specification data was raised, the colonel stated, ‘Forget all about that: When can you get us 100,000 pieces?’ I was dumbfounded; it was the largest order I had ever taken. At the time, we probably had no more than 100 T45s on the shelf.”

Needless to say, that type of demand necessitated enlargement of manufacturing space and a corresponding increase in labor. Kahn marched down to see his banker, and on the strength of his military orders, funding was advanced quickly.

EV swiftly moved to secure additional production facilities in Buchanan MI. Working three shifts a day, seven days a week, EV was soon shipping T45 microphones in the thousands per day. Kahn recalled, “I would get a call from the War Department every morning asking how many pieces we could ship that day, and they would dispatch a B25 bomber to South Bend to pick up the prior day’s production run. At one point, one of the tires on our old delivery truck gave up, and the local ration board refused us when we petitioned for a new tire. When the War Department learned of our dilemma, the fur flew—and we had a new tire by the next morning.” Kahn proudly related that Electro-Voice’s contribution to the war effort was conducted totally royalty-free and won them a coveted Army/Navy “E” Award.

Post-War Years

The T45 survived for decades as the mainstay microphone for voice communications in the commercial aviation market. And it saw use in the space age during the Mercury, Gemini and Skylab space missions.

Under Kahn’s direction, the company geared up to meet the pent-up consumer demand that had languished during the war years. Although microphones were still the prime business, the engineering department was encouraged to explore diverse avenues. Television and FM radio were in their infancy, and reception of signals was an iffy proposition.

The T45 survived for decades as the mainstay microphone for voice communications in the commercial aviation market. And it saw use in the space age during the Mercury, Gemini and Skylab space missions.

One morning, a young engineer named Daniel Tomcik came into Kahn’s office and announced that he had built an antenna booster for his home TV. Kahn was intrigued and asked to see a sample. The device worked—and engineering was set up to refine the device for consumer consumption. This element of the business grew rapidly and profitably, and soon included FM boosters, UHF converters and other electronic devices for the home market. By that time, Kahn had purchased the RME Company in Peoria IL, a small manufacturer of amateur radio and military communications equipment. The TV and FM accessory business was shifted to the Peoria plant.

Another post-war venture was the decision to start producing phonograph cartridges. The leading producer of crystals suitable for use in phonograph cartridges was the Brush Corporation of Cleveland OH. Kahn approached them with the purpose of purchasing crystals for EV’s new line. Brush was reluctant to enter into an agreement unless the EV device relied on different principles than those currently in vogue. As a result, Kahn set EV’s engineering department to work in developing a new cartridge that would differentiate the EV device from others. In short order, they had a radically new design ready for production—and Brush started shipping crystals. Kahn then strengthened the offerings in this product line by acquiring the Jensen cartridge business.

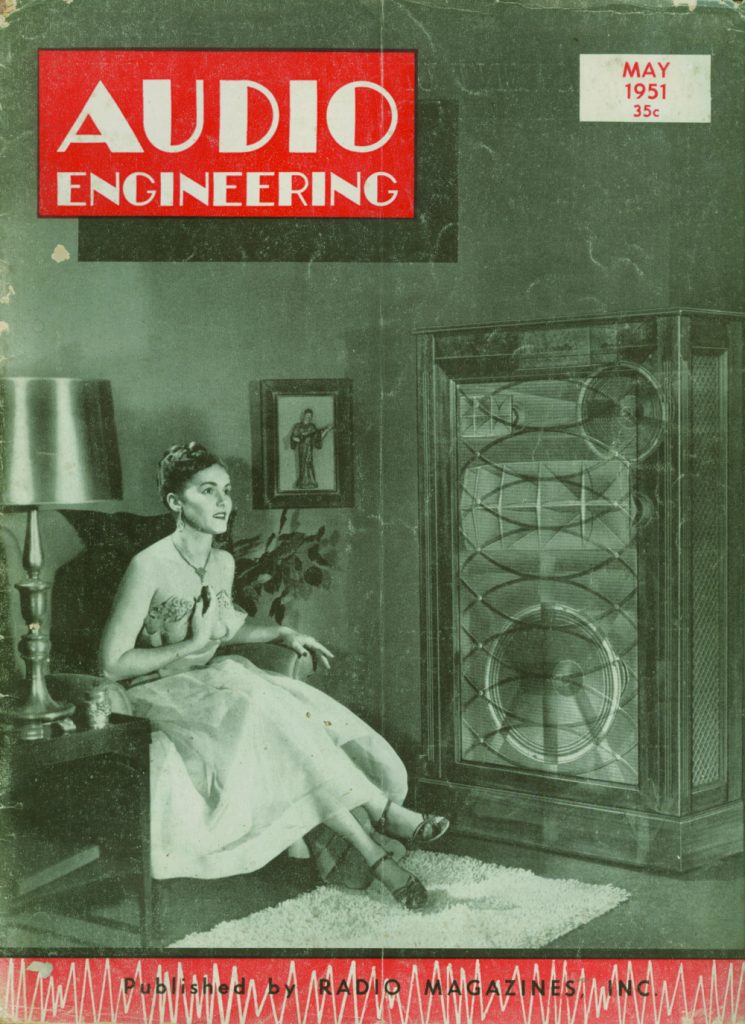

Business Blossomed

The loudspeaker business that had been placed on hold during the war years also started to blossom. Initially, the emphasis was on consumer products and caught the leading wave of the soon-to-be-burgeoning hi-fi market. The major distribution of this business was aimed at the jobber sales market; however, the company also enjoyed sizable sales to OEM accounts that were negotiated with firms such as Admiral, Crosley, Seeburg and Montgomery-Ward.

Success in hi-fi soon led to ventures into the commercial loudspeaker business. An investment was made in the construction of a large anechoic chamber, which at the time was the largest such chamber outside of academic research facilities. The world-famous CDP horn was developed during this period, and EV was off and running in the commercial loudspeaker business.

Growth and Adversity

When asked whether there had been any significant patent litigation during his tenure with Electro-Voice, Kahn could recall two instances. “In one case, a competitor complained that we were infringing on one of its patents relating to microphone design,” he described. “I set our engineering and legal departments to work investigating the claim. The report came back that, yes, we probably were guilty of the charge. However, it also appeared that Jensen was infringing on some of our patents.” To round out the story, Kahn called Jensen and apprised them of the developments. “We decided to cross-license our patents, and the problem was resolved.”

The business grew rapidly and profitably, and soon included FM boosters, UHF converters and other electronic devices for the home market. Another post-war venture was the decision to start producing phonograph cartridges.

“In the other case,” Kahn related, “we were hit with a suit from Shure brothers claiming infringement with regard to porting of microphones. We felt that our procedures were sufficiently different, and the case wound up in litigation. Shure called on the renowned Dr. Hugh Knowles as an expert witness; we engaged Dr. Knowles’ boss as our expert.” The case was settled in EV’s favor.

Kahn said he had always maintained cordial relations with his work force and, capitalist that he is, he resented the intrusion of organized labor into his operations. When labor in Michigan became increasingly militant, he countered by shifting the production of microphones and loudspeakers to non-union plants in Sevierville and Newport TN, respectively.

The loudspeaker business that had been placed on hold during the war years also started to blossom. Success in hi-fi soon led to ventures into the commercial loudspeaker business.

Always sensitive to feedback from customers and dealers, Kahn and Burroughs frequently toured the country extolling the virtues of their products and listened carefully as comments—both positive and negative—were voiced. As the late 50s evolved into the early 60s, Kahn’s travel diminished—but it was the era of the Lou Burroughs’ Medicine Show, a staging that many “old timers” recall with fond amusement. Kahn laughingly observed, “Lou had an unlimited expense account—and he always managed to exceed it.”

The Gulton Era

In 1969, Electro-Voice merged with Gulton Industries; Kahn sat on the board of the newly formed company for several years. “I was not cut out to run a public-owned company. In many ways, it was anathematic to everything I had done in my lifetime,” Kahn stated. Disagreeing with some of the new management’s decisions, he resigned and left EV for good.

In 1969, Electro-Voice merged with Gulton Industries; Kahn sat on the board of the newly formed company for several years.

In 1970, he started an amateur radio manufacturing company called Ten Tec and remained active until about two years ago. At age 95, when his wife of 64 years, Anne, died, Albert Kahn decided once and for all that it was time to spend his remaining years with his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Kahn’s Recollections

Kahn is fond of saying that a lot of his success in business was in selecting some very talented people who could take his ideas and translate them into reality. When asked if he would have done anything differently during his lifetime in business, he looked at me with a twinkle in his eyes and pontificated, “No, I don’t think so. I achieved some degree of success in my endeavors. Made many good friends—and friends are very important. I’ve had a very full and rewarding life. I was able to help see my children and my grandchildren through college and attain the education that I never had.”

This article was originally published in the March 2004 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.