Paul Wilbur Klipsch (1904-2002) was born in Elkhart IN on March 9, 1904, the only offspring of Oscar W. and Minna Eddy Klipsch. His father could trace the Klipsch history as far back as 1610 to Hallë, Germany. His mother claimed descent from the Abernathy clan of Scotland, said to herald from Nathan, King of Scotland (600AD), and which was reputed to be related to the royal House of Bruce.1

Oscar Klipsch taught mechanical engineering at Purdue University and instilled in young Paul an interest in mechanics and in most anything that involved vehicles and movement. Paul’s early love affair with railroads and railway locomotives was an enduring passion. One of his cherished possessions was a meticulously detailed, hand-built, air-driven brass “O” scale model of a Southern Pacific steam locomotive (this same model would later hold a prominent place of honor in the Klipsch Museum of Audio History in Hope AR). Jim Hunter, unofficial curator of the Klipsch archives in Indianapolis IN, noted that he uncovered a notebook in which Paul Klipsch had immaculately detailed his 20-year research and development of the scale model, a pursuit for which he had turned and lathed all the brass parts from raw stock and for which he molded the dies to produce the brass driving wheels.

Klipsch’s father, Oscar, was fond of describing himself as “a mechanic with a college degree,” a phrase that Paul, in his self-deprecatory manner, often used to describe his own exploits.

Likewise, Klipsch’s lifelong interest in airplanes and flying was fostered when, in 1911, he accompanied his father to an air show at Purdue Stadium and witnessed Lincoln Beachey piloting a single-engine pusher plane. An early exposure to the marvels of the emerging age of radio added to Klipsch’s interest in a mix of things mechanical. Paul Klipsch’s father, Oscar, was fond of describing himself as “a mechanic with a college degree,” a phrase that Paul, in his self-deprecatory manner, often used to describe his own exploits.

Youth And Education

When Klipsch was only eight, his family’s life in West Layfette IN was torn asunder when his father was diagnosed with tuberculosis. On doctor’s orders, they relocated to the drier climes of the Southwest where they took up residence in the small Arizona mining town of Congress Junction. They later moved to a home near Tucson AZ where his father was committed to a tuberculosis sanitarium.

The young Klipsch was smitten with an interest in electronics during the early days of radio. At age 14, he built a wireless crystal radio receiver that could receive Morse code messages from ships far out to sea.

Although gravely ill, the elder Klipsch continued to guide Paul’s interest in mechanical engineering and provided answers to his son’s questions with a frequent reference to the Kent Handbook of Mechanical Engineering. Oscar Klipsch was laid to rest on August 22, 1916, when Paul was barely 12.

The following years were difficult as Paul Klipsch’s young-widowed, strong-willed mother Minna ran a boarding house, pursued a college education to become a teacher and saved money that would be tapped to send Paul to college. Her teaching degree served her well, and, despite frequent relocations, teaching provided a relatively steady income for the young family.

Like so many of the industrial pioneers we have explored in this series, the young Klipsch was smitten with an interest in electronics during the early days of radio. While residing in Lordsburg NM at age 14, he built a wireless crystal radio receiver. This, of course, was prior to regular radio broadcasting, but his “home-brew” radio could receive Morse code messages from ships far out to sea.

Klipsch’s young-widowed, strong-willed mother Minna ran a boarding house, pursued a college education to become a teacher and saved money that would be tapped to send Paul to college.

By 1919, Klipsch was living in El Paso TX, where his fledging knowledge of radio and audio prompted him to build his first loudspeaker, a contraption consisting of a cardboard tube and an earphone, which he later described as “not working very well.”2

Klipsch And His Timepieces

One of Klipsch’s lesser idiosyncrasies was his habit of wearing or carrying four watches (another quirk, which has to do with Gothic script on a large yellow button, will be covered later). His pocket watch, which he considered his “standard timepiece,” was set to Greenwich Mean Time. One of his wrist watches usually was maintained on New York City (Eastern time), although no one—including Klipsch—ever explained why NYC was the chosen field. Setting of the second wrist watch varied to suit the particular time zone in which Klipsch happened to be at any given time. And, the fourth chronometer displayed either the Hope AR time (Central US time-zone), or the local time of his current location.

Perhaps this obsession with watches is in part explained by the story of when his mother bought him a present upon graduation from high school: Mother and son entered a small jewelry store in El Paso, and Minna picked out a handsome new pocket watch to celebrate the occasion. The jeweler asked how the watch should be engraved (this was long before the days of dispensable, throw-away $5.95 Timex watches) and the proud mother intoned that her gift should be engraved with Paul’s monogram (PWK). At that, Paul interrupted and instructed the jeweler that all of the letters should be joined together, with the P attached to the first downstroke of the W and the K attached to the second upstroke of the W. The jeweler was perplexed and suggested that the P might be more balanced if drawn backward. Taking the jeweler’s suggestion, Paul drew out the final design. Thus, the famous PWK logo was created. (Note: The “Klipschorn” medallion was a later addition.)

College And Off To Chile

Klipsch’s college of choice was New Mexico A&M (now New Mexico State University) in Las Cruces NM, not far from El Paso. He always regarded this institution as his alma mater; in his acquired southwestern drawl, he fondly described it as “that cow collich.” Despite his father’s influence toward things mechanical, Klipsch’s exposure to wireless and things electronic steered him into courses geared toward achieving a degree in electrical engineering. Although never an outstanding student in high school, Klipsch found his college education fulfilling and became an active member of a number of engineering-related societies. Other extracurricular activities included playing cornet in the band, attaining the rank of captain in the school’s ROTC program and gaining proficiency in small-bore rifle shooting. He often remarked that, “One of my life’s worst mistakes was outshooting my commanding officer.”

Despite his father’s influence toward things mechanical, Klipsch’s exposure to wireless and things electronic steered him into courses geared toward achieving a degree in electrical engineering.

Perhaps foretelling his continued interest in audio, Klipsch noted that, during a visit to his mother, he noticed that she had set her Edison phonograph in a corner of the room. Visually, the location was all wrong, but it sounded better, a fact that apparently didn’t escape Klipsch during his subsequent explorations of “corner horns.”

Upon graduation from New Mexico A&M in 1926 with a BSEE (Bachelor of Science, Electrical Engineering) degree, Klipsch got a job with General Electric in Schenectady NY, where his duties involved the design of radios that GE was selling to RCA. A job opening posted on the company bulletin board piqued his interest in what was announced to be a position in GE’s locomotive department. With his undying passion for railroads and locomotives guiding him, Klipsch sought assignment to the company’s locomotive manufacturing plant in Erie PA. GE was turning out electrical locomotives at this facility, and Klipsch took note of some units that were being prepared for export to Chile. Thus, in 1928, he applied to be, and was chosen as, the company’s commissioning and maintenance representative for GE engines being shipped to the Anglo-Chilean Consolidated Nitrate Corporation’s Railway in Tocopilla, Chile (see sidebar below).

Prior to his departure for Chile, Klipsch had paid a visit to his mother’s home in El Paso. It was there, on his mother’s front porch, that he met his future bride, Eva Belle Hulling. Klipsch was enamored, and before the visit was over he proposed to Hulling, who was also smitten. However, her father was less than keen about the idea of his daughter marrying on such short notice and then departing for some strange land with a new husband who had not yet established himself in his new job.

Klipsch departed for Chile accompanied by fond memories of his new sweetheart. Shortly thereafter, he arranged his affairs in Chile and returned to the US with the express purpose of transporting her back to Chile to get married. Paul and Belle Klipsch were married by Captain Renault, the master of the ship that transported them to Chile.

A colleague loaned Klipsch a crude, plaster-molded, serpentine folded horn loudspeaker, which he powered from a 0.7 watt amplifier. The cone loudspeakers that Kellogg and Rice had introduced in 1926 required a five-watt amplifier to play adequately. This convinced Klipsch that “the horn is more efficient, and higher efficiency equates to lower distortion.”

Despite the fact that his Chilean employment had little to do with radio, Klipsch continued to dabble in that field. His notebooks reveal that he and some associates put together a shortwave radio receiver, and a colleague loaned him a crude, plaster-molded, serpentine folded horn loudspeaker, which he powered from a 0.7 watt amplifier. Experiments with one of the newfangled cone loudspeakers that Kellogg and Rice had introduced in 1926 (which he found required a five-watt amplifier to play adequately) convinced Klipsch that “the horn is more efficient, and higher efficiency equates to lower distortion.”

Studies At Stanford

On August 28, 1931, Paul and Belle departed Chile for the US. They were somewhat dumbfounded to learn that their funds had evaporated when their US bank failed in the “loath of the depression.” With what little funds remained, he promptly enrolled in Stanford University to pursue graduate studies in electrical engineering. To fund his education and keep their heads afloat, the Klipsches took up the freelance pursuit of developing film, and Paul graded undergraduate papers. Two notable students with whom he worked where Messrs. Hewlett and Packard. Klipsch’s own graduate study was under the tutelage of Dr. Fredrick Termin, who went on to be known as the “Founder of Silicon Valley.” Klipsch, in his own intrepid way, was to note of Stanford, “It was the only place where they take two years to give you something a little beyond a master’s but not quite a doctorate.”

Klipsch’s master’s thesis was on “circuits for pentagrid converter tubes,” which was published in The Proceedings of the IRE. To illustrate his divergent interests, and perhaps prompted by his part-time employment, Klipsch also presented a paper to the Electrical Engineers of Stanford in 1932 entitled “Photography: Its Engineering Aspects.”

Klipsch’s observations also led to further investigations of the benefits of “corner placement” for loudspeaker playback devices.

Along with a host of other pursuits, Klipsch’s innate interest in radio and increasingly in the area of audio led him into some joint measuring exercises of loudspeakers with a classmate who was related to the Jensen family (Jensen being the manufacturer of many of the early cone loudspeaker devices). Their measurements confirmed Klipsch’s earlier observations that horn devices provided much greater efficiency, and that engineers in the fledgling audio industry were ignoring the basic physics of baffle designs [see “Industry Pioneers #1: Lord Rayleigh”]. Klipsch’s earlier observations also led to further investigations of the benefits of “corner placement” for loudspeaker playback devices. Klipsch’s investigations into loudspeaker designs prompted his mother to refer to his research as “his invention of an audio gadget.”

Geophysics

Klipsch received his master’s degree in electrical engineering from Stanford in 1934, and he and Belle promptly relocated to Houston TX where Paul was employed by Dr. E. Rosiare in a variety of positions having to do with geophysical exploration. This phase of Klipsch’s career lasted until 1941, during which time he was awarded eight patents, most of which were related to geophysical exploration for oil by means of electrical analysis of the properties of the earth’s crust.

The major legacy from this era was realized when Klipsch’s employer lost interest in acoustical processes for oil exploration and donated to Klipsch his back issues of the JASA (Journal of the Acoustical Society of America), commencing with Volume 1, Issue 1 (1929-1940). These journals constituted the nucleus of an extensive audio engineering library. (Klipsch, fortunately, was an avid packrat and saved most of the publications to which he subscribed, so his files and journals still survive almost intact. And thanks to the efforts of Hunter and others at Klipsch Audio Technologies in Indianapolis, we still have access to most of these artifacts.)

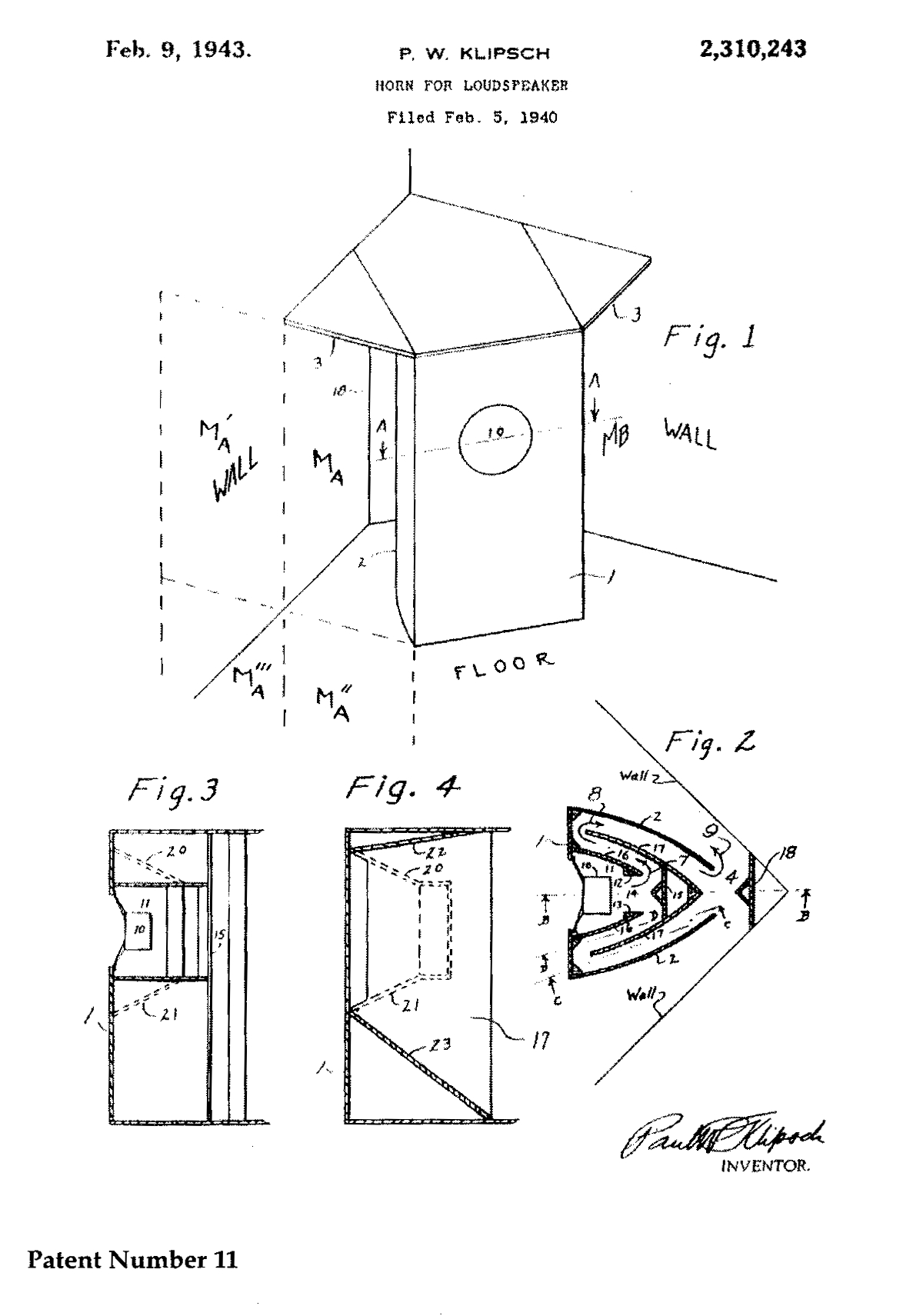

Despite his devotion to his “day job” in the field of oil exploration, Klipsch continued his experiments in loudspeaker development. Using nothing more exotic than common hand-tools—and a lot of glue—he constructed several corner-horn enclosures and some wooden high-frequency horns, most of which were utter failures. After several stabs at the development of a successful device and the use of lots of lumber, Klipsch struck upon the combination of a high-efficiency folded horn with a corner placement for the successful reproduction of audio.

The physics of the matter was that, to achieve a 40Hz playback, the mouth opening of the device had to be at least 8.5 meters in circumference. And, if this is applied to determine the radius of the horn mouth, then:

radius = speed of sound/πf.

However, if the device is corner located to take advantage of the created exponential horn, then a 1/2λ solution can be achieved. Hence, the dimensions of the original full-wave radius, and the subsequent humongous enclosure, could be constructed to result in a cabinet that, while still substantial in size, would be more acceptable aesthetically. The other aspect of the design was the transparency of the fundamental frequencies without the coloration introduced by harmonic generation. In those days, when amplifier power was hard to come by and very expensive, the emphasis was on efficiency.

Klipsch filed a patent for his speaker system, but it was rejected on the grounds that it covered work previously assigned to Paul Voight, a German expatriate residing in England and working for Edison Bell.3 Faced with Voight’s antecedence in design, Klipsch revised his original filing to more specifically describe the shape of his folded horn in what he blithely noted was the “widest bandwidth/per cubic bulk,” and the patent was registered.

Not A Typical Project

By 1941, the war was raging in Europe, and it appeared likely that the United States would become embroiled in the cauldron to an ever greater degree. By virtue of his ROTC service, Klipsch was called to active duty and reported to the Aberdeen (MD) Testing Grounds. The Army wasn’t quite sure what they would do with a 37-year-old lieutenant, so in true military fashion, they stuck him into a Military Police detachment. He might well have served out his war years in that capacity but for Washington’s notice of his earlier experience in marksmanship and research in ballistics; he was promptly assigned to a new ballistic testing range that had been carved out of the woods and farmland in the southwestern portion of Arkansas near the small community of Hope.

Klipsch commented that, “This work is hardly a typical project for an electrical engineer with graduate work in electronics and research experience in geophysics.” However, he was diligent in his work and was awarded a patent for improvements in the testing of artillery projectiles.

Klipsch’s experience in photography and velocity measurements was put to good stead as he and his group strove to improve the testing procedures of fired artillery projectiles. A common problem was in identifying those shells that could wind up as being “short rounds,” which are rounds that would wind up falling short of their target—often with disastrous results if they fell into the ranks of advancing allied soldiers.

Klipsch commented that, “This work is hardly a typical project for an electrical engineer with graduate work in electronics and research experience in geophysics.”4 However, he was diligent in his work and was awarded a patent for improvements in the testing of artillery projectiles. Klipsch was promoted to Captain in the Signal Corps and later to Lt. Colonel in the Reserves (1953).

Klipsch was separated from active duty in 1945 and he remembered, “At the separation center, I filled out a questionnaire about what kind of a job I wanted. I said I intended to manufacture a loudspeaker on which I held one patent and one patent application. A young lieutenant endorsed the sheet: ‘The above named officer has no previous experience in the manufacture of the proposed project.’”5

Klipsch Put Hope On The Map

The young lieutenant’s dismissive note on Klipsch’s separation papers was an obvious caustic effrontery and, to some degree, rather prophetic. That it did not sway Klipsch from his hard-headed ambition to produce the finest possible loudspeaker is undoubtedly a credit to his tenacity. He, like so many others, suffered from the malady of being a brilliant engineer, but was sorely lacking in sales/marketing acumen and practical business sense. Nonetheless, he started his own speaker-manufacturing business.

Klipsch & Associates was, of course, a privately held company, and precise dollar figures for the operation are vague; however, it is widely circulated that the company was constantly in the red from its founding in 1946 until about 1958. That year, Klipsch’s mother passed away and left him a small inheritance that was folded into the company and provided some of the wherewithal to expand its operations.

From 1946 through 1947, the year’s production of “Klipschorns” amounted to 20 pieces. For production year 1948, the fledgling company hired a cabinet-maker as its first employee, and produced 26 units.

Klipsch trudged on and fortunately was able to acquire some manufacturing space when the military abandoned the southwest testing grounds. Setting up offices in what had been the old Instrument Building when it had been US government property, Klipsch used to brag that “My office desk is about seven feet from where it was when I was a Captain here in the Army.”6 He made contact with two local businessmen with the hope of attracting some capital. However, when they learned that his unorthodox loudspeaker would have a sales price of $400 each (about the price of a Ford car in 1946 dollars), they quickly lost interest.

From 1946 through 1947, the year’s production of “Klipschorns” amounted to 20 pieces. Under contract, Baldwin Piano Company made units two through 13, and a local cabinet shop turned out the remainder. For production year 1948, the fledgling company hired a cabinet-maker as its first employee, and produced 26 units. The 1948 serial numbers commenced with number 121, so as to not give customers the impression that Klipsch was just a small upstart company.

Prior to the advent of Klipsch & Associates, Hope had been a sleepy little rural town whose primary claim to fame was the 1935 production of the world’s largest watermelon. But Klipsch’s speaker-manufacturing endeavors served to put Hope on the map.

Klipsch was a civic-minded individual, a 33rd degree Mason, a Rotarian and a firm believer in a higher power, and thusly lent his time and resources for the betterment of his adopted home, Hope AR. Prior to the advent of Klipsch & Associates, Hope had been a sleepy little rural town whose primary claim to fame was the 1935 production of the world’s largest watermelon. But Klipsch’s speaker-manufacturing endeavors served to put Hope on the map. For many years, a sign hung over the main street (long since bypassed by the interstate) stating, “Hope, Home of the Klipschorn.” And, people still detour to visit the Klipsch museum and woodworking facilities there.

Aviation, Other Pursuits

A man of many interests, Klipsch continued his avid aviation enthusiasm. In 1950, a life-long ambition was fulfilled when he became a licensed pilot. The city of Hope had acquired the landing strip that was built by the military, and it became the convenient home for a series of Klipsch-owned aircraft.

This writer can recall Klipsch picking me up at the airport in Texarkana one morning and driving me in his Mercedes to the Hope plant. (And, yes, in those pre-interstate days, his devil-may-care driving was something to behold. But on the other hand, his flying habits were an exercise in caution and forbearance.) After a day of conversation, I announced I had to depart to catch a plane for New Orleans. “Nothing doing,” Klipsch replied. He was adamant that he would fly me to Shreveport to catch my flight. I protested, but a deal was struck: Hempstead County (where Hope is located) was dry, and Klipsch’s liquor cabinet was in need of refurbishing, so a flight to Shreveport would correct that problem. I agreed, in turn, that supper would be on me. So Paul, Belle and I piled into his Beechcraft for the short flight to Shreveport. Paul advised that he had just had the aircraft’s navigational equipment overhauled, but nonetheless our flight followed the contour of the Red River at an altitude of about 1000 feet. As for our dinner, Shreveport has any number of nice restaurants, however, at Paul’s insistence, we wound up having supper at a less-than-posh oyster bar on lower Texas Street.7

“Asking Paul a question about audio is like trying to take a drink from a fire hydrant.”

Paul Klipsch had a mind like a steel trap, an attribute that longtime Klispch employee and eventual company President Bob Moers is first credited with quipping, and that was oft repeated by his mentored horn designer Ray Delgado; they would remark that “Asking Paul a question about audio is like trying to take a drink from a fire hydrant.” Klipsch definitely was a walking encyclopedia when it came to the subject of audio and loudspeaker design.

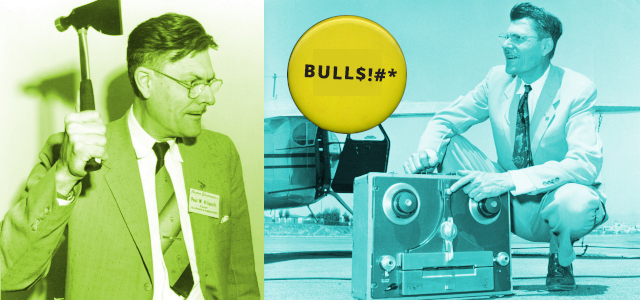

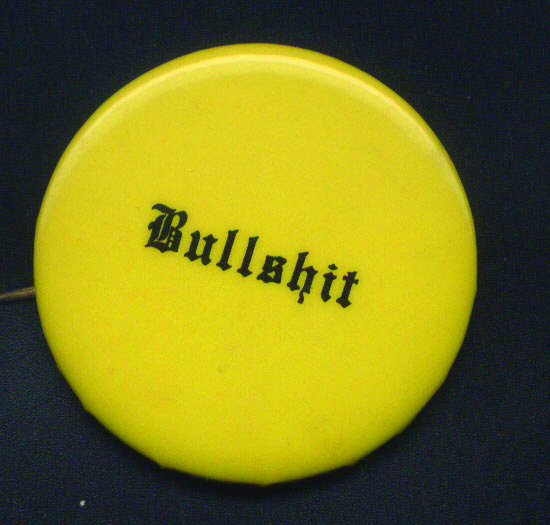

“Bullshit!”

Klipsch also suffered fools poorly, and his iconoclastic nature was exemplified by one of his trademarks: the caustic response “Bullshit!” This catchphrase was famously printed on bright yellow T-shirts worn by his company’s employees, and it later took the form of a small yellow button on which the pronouncement was inscribed in Germanic Gothic script. When confronted with what in his mind’s eye were questionable statements, Klipsch was not at all adverse to flipping open his suit-jacket lapel and displaying one of these buttons bearing this somewhat bawdy but to-the-point comment. The buttons were given away at trade shows and were also awarded as necessary by Klipsch himself. Many of us who knew Paul cherish one of these famous buttons, even though the receipt of one might have been occasioned by what he considered an erroneous statement on our part. Usually, he was right.

Beyond The Klipschorn

Certainly, the Klipschorn alone would have guaranteed Klipsch’s standing as a pioneer in the development of loudspeaker science. The loudspeaker that he introduced to the audio industry in 1947 has more than stood the test of time and, even in 2005, the Klipschorn is still a production product with an ardent audience of customers willing to spend considerable sums to experience the excellent tonality of his superb design. Klipsch is credited with once saying, “What do you have when you take several pounds of high-grade adhesive, 576 nails and screws, 118 hand-cut, hand-sanded birch plywood boards and 20 hours of hand-construction? A matched pair of Klipschorns.” Workmen in his shop were known to remark that, “A Klipschorn’s physical integrity is usually superior to, and will likely outlast, its owner.”

There can be no doubt that a Klipschorn was, and is, a remarkable audio-playback device. However, there was also a high degree of aesthetic consideration in its manufacture. A Klipschorn was indeed a truly fine piece of furniture. They were also designed to exacting standards; a loudspeaker whose only sin was having a bad wood grain match to its partner was destined for salvage. Another outstanding trait displayed by Klipsch’s loudspeaker cabinets was the use of tapestry-like grille work; the resulting grilles were works of art unto themselves.

During the 1950s, Klipsch revisited the work that had been done by Bell Labs in the early 1930s related to the spatial balance of multi-channel loudspeaker propagation. This brought forth several models of loudspeakers that addressed the playback of “center”-channel audio in conjunction with corner-mounted Klipschorns. One such endeavor was the creation of the Series H that, in an enduring myth, was dubbed the “Heresy” for deviating from Klipsch’s corner-centric design principles. As the sometimes-questioned story goes, when the H-Series was introduced, one of Klipsch’s distributors remarked that it seemed like blasphemy for the dedicated proponent of corner horns to even consider the manufacture of such a device—sheer heresy, the man noted. Hence, Klipsch seized on the pronouncement and promptly named the new device the Heresy.

Eargle’s Contribution

John Eargle, who briefly worked at Klipsch in 1956 between his mustering out from the military and before he trooped off to Austin TX to attend the University of Texas Engineering School, contributed to the development of two-track to three-track derived stereo. When questioned about his involvement, Eargle responded, “I never thought of the Klipsch-Eargle circuit as much of an invention, and it was really Paul who came up with the idea for deriving a signal to fill in the usually enormous spatial gap between left and right K-horns. We discussed just how much attenuation the circuit should have in order to create a usable center feed without causing the overall stage width to collapse.”

Eargle was also named in a 1958 Klipsch promotional piece as being the organist playing the keyboard of an Aeolian-Skinner organ at the First Presbyterian Church in Kilgore TX. These were subsequently transformed into some “test-tapes” for the newly formed Klipschtape division. With regard to his other duties at the Klipsch lab, Eargle noted, “Otherwise, I helped around the lab wiring crossovers and the like and, mostly, got in Paul’s way.”8

Playing At The World Fair

At the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, in what some local publishers dubbed the “Battle of Sounds,”9 Klipschorns became a major component of the US pavilion’s display of (then) contemporary US hi-fi components. Don Davis (of SynAudCon), who later became a prime player in the development of the Altec Lansing Acousta-Voicing program [see “Industry Pioneers #11: C.P. Boner, Father of Audio Equalization”], was at the time Klipsch’s national sales manager. The full story of how Davis, his wife Carolyn and Bill Bell teamed up to provide a truly US hi-fi experience at the fair is well documented in the recent book by the Davises If Bad Sound Were Fatal: Audio Would be the Leading Cause of Death.10

US Equipment Provided for the Brussels World Fair

2 Ampex 350-2 tape machines

1 Fairchild electronic drive turntable with 2 arms

2 Marantz amplifiers

2 Marantz pre-amplifiers

2 Klipschorn loudspeakers

Klipsch could definitely succumb to fits of anger, and this trait was displayed when the Davises went on an unauthorized tour after the Brussels World Fair and took their display to Russia. Klipsch took particular umbrage at this excursion behind the Iron Curtain, and this bone of contention summarily resulted in Don Davis’ employment with Klipsch being short-lived.

No report about the life of Paul Klipsch would be complete without mention of his many traits that inspired humor and sometimes chagrin on his many friends and colleagues. He often wrote under the nom de plume of O. Gadfly Hurtz (or Hurtcz) and his witticisms were classic. Audio Magazine in its August 1980 issue11 cataloged many of the “isms” attributed to O. Gadfly Hurtz:

- On brand recognition: “I had a local woman apply for a job here once, thinking we made paper clipsch. She probably still does.”

- On language: “How the hell can a plane land on water? It has to alight on water. People are always telling me things that just can’t be true. They’re talkin’ about original copies, permanent change, modern nostalgia, rubber corks, plastic glasses….Wish they’d figure out what they were sayin’. (They should look up the word “oxymoron” in any dictionary.)”

- On horn design: “Simple. A horn is just a reasonably rigid boundary for an air column. Now all you have to do is figure out what shape to make it.”

- On rock & roll music: “If hell is like this, I don’t want to go there.”

Other Klipsch witticisms and observations included:

- “Audio is plagued with false prophets, as is religion, and the difficulty lies in sifting the true from the false.”

- “A musician takes years and years to accomplish the art, but a critic can become a critic overnight.”

- “Success at last! (I found my teddy bear!)”

His driving habits, already mentioned, were perhaps histrionic, along with his peculiarity of keeping an altimeter mounted on the dashboard of his auto. And the following tale expresses his utter contempt for what he considered “bad” music. Returning from an auto repair shop where his Mercedes was serviced, he noted that the mechanic had taken the liberty of changing his selected radio station to one that was broadcasting what Klipsch considered “God awful music.” He put up with the distraction and distortion for a few miles, pulled over, pulled his tool box out of the trunk, ripped the radio out of the dashboard, stuffed the hole with a pillow and drove on, remarking, “That’s better! Now we won’t have to worry about that bullshit anymore.”

Philanthropy And Accolades

Klipsch always considered New Mexico A&M his alma mater, and he and the second Mrs. Klipsch, Valerie Klipsch nee Booles, contributed significantly to that school. Their endowments have allowed for the establishment of the Klipsch School of Electrical and Computer Engineering on the Las Cruces campus. A scholarship fund for engineering students was established in 1977 along with the opening of the Paul W. Klipsch museum. A locomotive bell salvaged from engine number 65 of his Chilean railway days was donated and dubbed “The Chile Bell,” and is rung every time an electrical engineering student gets an “A.” And the school’s newsletter is appropriately named The Klipsch Speaker.

Klipsch’s other philanthropic interests include scholarships for the San Pueblo Indian Endowment, Wildrock Park for the Performing Arts in Little Rock, the Little Rock Symphony, and the Masons and Eastern Star Special Programs for Dyslexic Children.

Klipsch’s achievements in the field of audio award recognition are likened frequently to being the Triple Crown of Audio.

Paul W. Klipsch was awarded the Audio Engineering Society’s highest honor, the Gold Medal, in 1978 for his contributions to speaker design and distortion measurements. A Fellow of the Society, he was inducted into the Audio Hall of Fame in 1984.

Sharing honors with other notable industry pioneers, Klipsch was inducted into the Engineering and Science Hall of Fame in 1997. He was also a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), a Fellow of the ASA and a recipient of that society’s Gold Certificate signifying 50 years of membership. His achievements in the field of audio award recognition are likened frequently to being the Triple Crown of Audio.

At the time of his passing, Fred Klipsch, Paul’s cousin and current owner and chairman of Klipsch Audio Technologies, eulogized Paul by saying, “It has been said, and I firmly believe it, that every time you listen to recorded music, you’re hearing the passion, the genius and the legacy of Paul W. Klipsch. He was a verifiable genius who could have chosen any number of vocations, but the world sounds a lot better because he chose audio. And the integrity of Paul W. Klipsch was beyond reproach. He was a great man who always tried to do the right thing in the right way.”12

Sidebar: The Anglo-Chilean Consolidated Nitrate Corporation Railway

This Chilean railway started retiring its steam locomotives and converting to electrification in 1924 after the property was purchased from its previous London-based owners by a New York consortium headed by the Guggenheim Brothers.

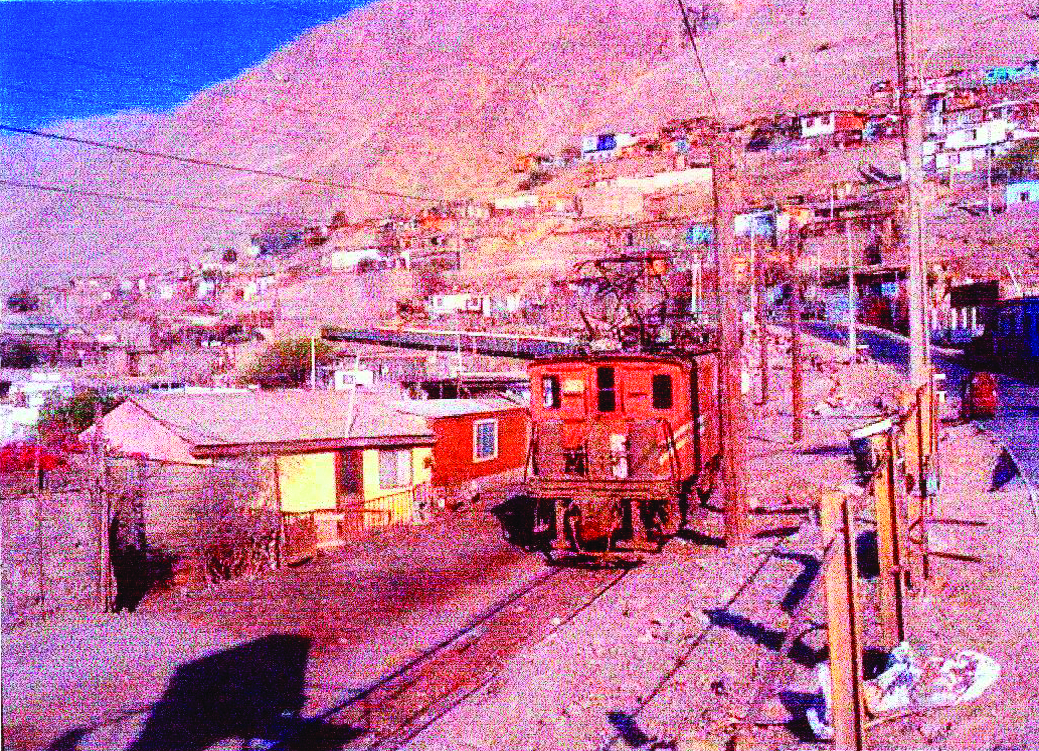

Paul Klipsch was dispatched to Chile in 1928 to commission and to arrange maintenance schedules for GE locomotives; the above photo, taken in 1998, shows one of the original eight units typical of the GE locomotives that Klipsch would have serviced. As of 2004, this engine was still in operation by the Anglo-Chilean Nitrate Corporation’s successor Servicios Integrales y Transports, a subsidiary of the Chilean Chemical Co. Hence, after 76 years of faithful service, these units are still hauling nitrate ore across the “lunar landscape” of Northern Chile between Tocopilla and Barrilla.

Needless to say, it would seem that Klipsch’s initial commissioning has stood the test of time. After some three years serving as superintendent of Locomotive Maintenance for the railway, he returned to the United States. His grateful staff awarded him a certificate that, roughly translated, reads, “The personnel of this section that has labored under his direction, has the honor of dedicating the memorial to our distinguished chief Señor Paul W. Klipsch with the motive of his departure from this town, doing so for personal happiness.”

References

- Barrett, Maureen and Klementovich, Michael; Paul Wilbur Klipsch, Rutledge Books, Inc., Danbury CT 2002; ISBN:

1-58244-226-6. - Barrett, et al, ibid.

- Lowther Loudspeakers, www.tnt-audio.com/casse/virtuoso_e.html.

- Klipsch, Diary of the War Years 1941-1945, unpublished.

- Klipsch, Ibid.

- Personal reminiscences by the author from various visits with Klipsch in the 1970s.

- ibid.

- The Shreveport Times, August 24, 1958.

- Eargle, personal correspondence with the author.

- Self-published, Bloomington IN, 2004.

- The Wit and Wisdom of O: Gadfly Hurtz (a.k.a. Paul Klipsch), Audio Magazine, August 1980.

- Klipsch Audio Technology’s Newsletter, www.klipsch.com/founder.

This article was originally published in the April 2005 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.