David Bogen’s life offers an enduring story of a young Russian Jewish immigrant who, by working hard and applying himself diligently, founded and guided a company that, to this day, is a leading supplier to the sound and communications industry.

Bogen was born in a small village some 200 miles from Kiev, Russia. Although, at times, he left listeners with the impression that his small village would have made an excellent backdrop for a scene from Fiddler on the Roof, he and his family were not an impoverished group of peasants. His father and grandfather owned property, operated a milling company and were, considering their times and circumstances, actually rather well off.

David Bogen’s life offers an enduring story of a young Russian Jewish immigrant who, by working hard and applying himself diligently, founded and guided a company that, to this day, is a leading supplier to the sound and communications industry.

According to his son Lester Bogen’s recollections,1 during his time living in Russia, young David was able to acquire what would be equivalent to a high school education, and his family had enough money to afford lessons for David to learn to read, write and converse in English. Seemingly, David chafed under the strict religious attitude of his elders and the stifling climate of the Czar’s authority. His ambition and the desire to put his English language skills to work led him to seek the more cosmopolitan enclave of Kiev. In that larger city, he was able to gain employment as a tutor, and his services were well received and rewarded. However, David eventually decided to immigrate to America. His brother, Israel, who was six years younger, recalled that David attended his Bar Mitzvah in 1909 just prior to David’s departure to the US.

Arriving In America

David Bogen debarked from his ocean passage to the US in Galveston TX. With no relatives or friends in this strange new land, he was utterly dependent on his own abilities. Although he spoke English with a distinct accent, his familiarity with the language was a decided asset. For the next two years, he roamed the southern tier of states and then back eastward through the northern states in pursuit of work.

Working at odd jobs, Bogen would stay in one place long enough to pay his keep and accumulate enough money to move onward. He often related that two of the jobs he found most interesting were as an iron worker in New Orleans, where he was engaged in fabricating the wrought-iron balcony railings and decorative gates that adorned the mansions in that city. He also found life as a section hand (track worker) on the Rock Island Railroad to be a fascinating experience. Although small in stature, Bogen was a wiry, physically adept individual who could hold his own with his rough and tumble fellow workers.

Furthering His Education

After having seen a fair amount of his adopted country, Bogen settled down in New York City and took a job with Consolidated Edison (Con Ed), the local electrical utility company. The nature of his work for Con Ed is not revealed; however, whatever the position, Bogen was eventually elevated to the rank of foreman. Smitten with an interest in electricity, he decided to pursue a career in electrical engineering. With no money other than his wages from Con Ed, his choices as to how he would further his education were severely limited.

Living in Brooklyn NY, Bogen would commute via subway and streetcar to his 10-plus-hour-a-day job at Con Ed, then make his way to Cooper Union on lower 14th Street in Manhattan to attend his evening courses.

Cooper Union appeared to be his best and, perhaps his only, option. That institution offered a tuition-free, accredited course of study for qualified applicants, merely for the asking. Attending full time, the required curriculum would take four years; this, of course, was out of the question. This was a time when an eight-hour-a-day, five-day work week was not the established norm; and Bogen was still faced with the need to make a living wage. The second alternative was to attend evening classes. That course of action would require attending classes for seven years; Bogen took this approach.

Living in Brooklyn NY, Bogen would commute via subway and streetcar to his 10-plus-hour-a-day job at Con Ed, then make his way to Cooper Union on lower 14th Street in Manhattan to attend his evening courses. He related that “his sleeping time was often accomplished on the NYC transit system.”2

After seven long years of study, Bogen gained his baccalaureate in Electrical Engineering. In those days of rampant anti-Semitism, he was refused employment at any of the large companies he approached, solely on the basis of his Jewish heritage.

After seven long years of study, Bogen gained his baccalaureate in Electrical Engineering. One can only imagine his dismay when, in those days of rampant anti-Semitism, he was refused employment at any of the large companies he approached, solely on the basis of his Jewish heritage. Nevertheless, Bogen was always grateful to Cooper Union for his education, was justifiably proud of his EE degree and, in later years, was a solid supporter of his alma mater.

Bogen’s Entrepreneurial Spirit

Despite circumstances that might have crushed a lesser individual, Bogen pressed forward and vowed to never again work for anyone other than himself. Tapping the meager savings he had accumulated as an employee of Con Ed, he began producing small cast-metal images of the Statue of Liberty, which were in demand as souvenirs of NYC. Revenues were adequate to keep him afloat.

Having finished at Cooper Union in 1918, Bogen was on the threshold to witness the immense surge of activity that swept the radio industry as consumers embraced this new technology. He abandoned his Statue of Liberty production and shifted his interest to the emerging field of electrical and electronic parts distribution.

As we have seen from previous accountings of such noteworthy individuals as Sidney Shure (see “Industry Pioneers #16: Sidney N. Shure: Integrity And Innovation”), Al Kahn (see “Industry Pioneers #10: Albert R. Kahn, Founder Of Electro-Voice”), E.N. Rauland (see “Industry Pioneers #15: E. Norman Rauland, American Industrialist”) and J.B. Lansing (see “Industry Pioneers #17: James B. Lansing: A Legacy In Sound”), the 1920s gave promise of handsome profits to those willing to risk their time and capital to serve this emerging industry. In rather short order, Bogen created a profitable distribution company serving that marketplace.

Having finished at Cooper Union in 1918, Bogen was on the threshold to witness the immense surge of activity that swept the radio industry as consumers embraced this new technology. He abandoned his Statue of Liberty production and shifted his interest to the emerging field of electrical and electronic parts distribution.

A turning point occurred when Bogen received an order for a substantial number of audio amplifiers. At the time, the only significant manufacturer of such devices was Western Electric. Western Electric resolutely refused to sell products to “third-party” distributors. Bogen sensed an opportunity and tooled up to provide such equipment to a growing number of potential customers.

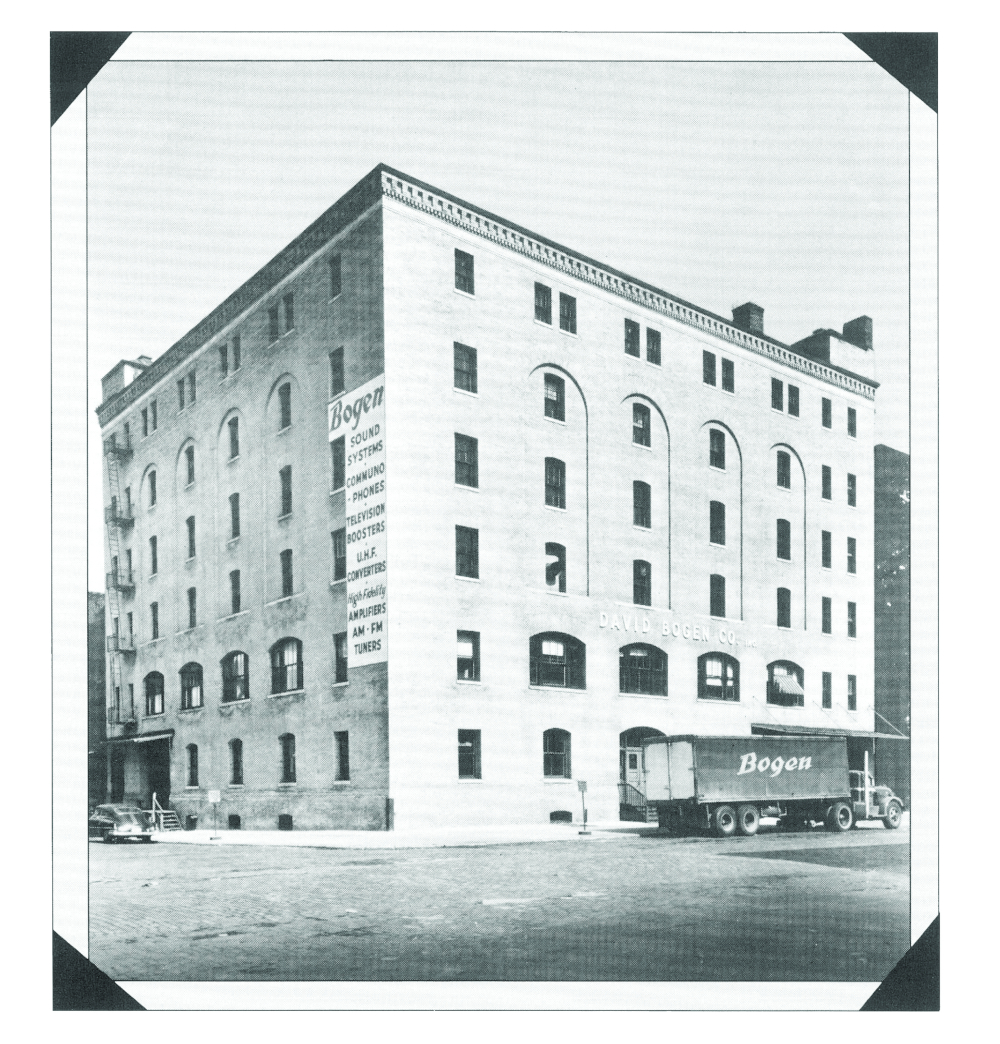

By 1932, the David Bogen Company transformed itself from being a distributor into the role of a manufacturer and started churning out audio amplifiers and other audio products, much to the chagrin of Western Electric, which always considered Bogen an “inferior usurper” in this regard. Western Electric and its counterparts at RCA were much too engrossed in their cinema activities and considered “commercial sound” much too mundane for any serious consideration.

Aspersions aside, the David Bogen Company created products that appealed to the commercial sector of the industry. Granted, 1932 was not exactly the best possible economic climate to launch a new company; however, the David Bogen Company prospered.

Venturing Into Recording

A holdover from Bogen’s distributing days was a line of variable-speed phonograph players. These were used by dance teachers and square dance callers who needed players that would accommodate the then-in-use 16-inch transcription discs and that could change speed in order to vary the rhythm. This was indeed a rather specialized market and was dominated by one domestic supplier. Electric motors for such devices were scarce and relatively expensive. When his supplier significantly ramped up their prices, Bogen went looking for an alternative source.

As chance would have it, Bogen had made the acquaintance of Harry Meyers, who held controlling interest in the Carl Fisher Musical Instrument Company. Meyers’ agent in Europe was Charlie Liebi, who was responsible for seeking out suppliers of musical instruments for import into the US. Bogen, having been introduced previously to Liebi, thought Liebi’s knowledge of European manufacturing might prove useful in solving his recording apparatus dilemma. With Meyers’ approval, Bogen contacted Liebi and engaged him as his agent in Europe. It proved to be a quite satisfactory relationship.

A holdover from Bogen’s distributing days was a line of variable-speed phonograph players. Electric motors for such devices were scarce and relatively expensive. Bogen thought Charlie Liebi’s knowledge of European manufacturing might prove useful in solving his recording apparatus dilemma.

In short order, Liebi cabled Bogen that he had located a small machine shop in Burgdorf near Bern, Switzerland, that might meet the criteria for providing the variable speed recording/playback apparatus that Bogen was seeking. Based on Liebi’s reports, Bogen was intrigued and booked passage for the trans-Atlantic voyage. What he found when he met with the Laeng family in Bern was an entirely satisfactory mechanical apparatus that served the purpose and that was considerably less expensive than the devices being offered by his previous domestic supplier. The downside was that the Laeng machine shop was just that: a shop and not a production facility.

Lenco AG & Bogen-Presto

Bogen and Liebi arranged a series of meetings with the town fathers of Burgdorf. Despite the two men’s almost utter incomprehension of “Switzerdeutch,” by using Liebi’s considerable amount of salesmanship and Bogen’s mien, a deal was struck. In exchange for a sustaining order for product and some financial assistance in tooling up for production, the town elders agreed to provide suitable factory space to support the enterprise. Hence, Lenco AG was founded. In the US, a Bogen subsidiary—Bogen-Presto—was incorporated to handle the import and distribution of recording apparatus.

The exact date of this transaction has been lost, but it can be surmised that this all occurred sometime in 1935-36. Lenco AG also contributed significantly to the development of telephone-style intercom systems that formed the base for Bogen’s entry into the office and institutional intercom market.

Bogen and Liebi arranged a series of meetings with the town fathers of Burgdorf, and the elders agreed to provide suitable factory space to support the enterprise. Hence, Lenco AG was founded. In the US, a Bogen subsidiary—Bogen-Presto—was incorporated to handle the import and distribution of recording apparatus.

Like practically every industry in the United States during World War II, the David Bogen Company geared up to provide materials for the war effort. Commercial sales shrank to practically nothing, and the US military became its largest customer. Bogen’s young son, Lester Bogen (1922-1988), whom David was grooming as his successor and who was already an active member of the David Bogen Company, marched off to war as an officer in the Army.

Hi-Fi Era

Never one to miss a promising opportunity, by 1949, David Bogen geared up to provide product for the emerging consumer demand for enhanced playback apparatus. Although the company shied away from loudspeaker transducer engineering or production, its electronic products were well received in the marketplace. Lester Bogen was placed in the position of overseeing this aspect of the company’s activities, a position he accepted with some reluctance.

Sound & Communications Relationship

During the early 1950s, Jerome Brookman was an ad salesman working for an electrical product magazine for “jobbers.” In that capacity, covering the Eastern seaboard, Brookman called on potential accounts such as the David Bogen Company and others in the audio manufacturing business. Brookman recalled that “David Bogen and some of the others in that segment of the industry repeatedly told me that the magazine I represented was not ‘reaching’ the segment of the industry that might be interested in buying their audio products.”3

In 1955, Jerome Brookman started Sound Merchandising Magazine, which later morphed into Sound & Communications. He was always eternally grateful that his initial solicitation for subscribers was based on David Bogen’s list of distributors.

Brookman heeded their advice and, in 1955, started Sound Merchandising Magazine, which later morphed into Sound & Communications. He was always eternally grateful that his initial solicitation for subscribers was based on David Bogen’s list of distributors.

David Bogen Company Legacy

Lester Bogen, from his high school days, had always displayed an interest in artistic rather than engineering aspects, and showed an early affinity for photography. He took his leave of his father’s company and founded Bogen Photography, a company that concentrated on the development and manufacturing of tripods, camera head mountings and sundry accessories for the photographic industry.

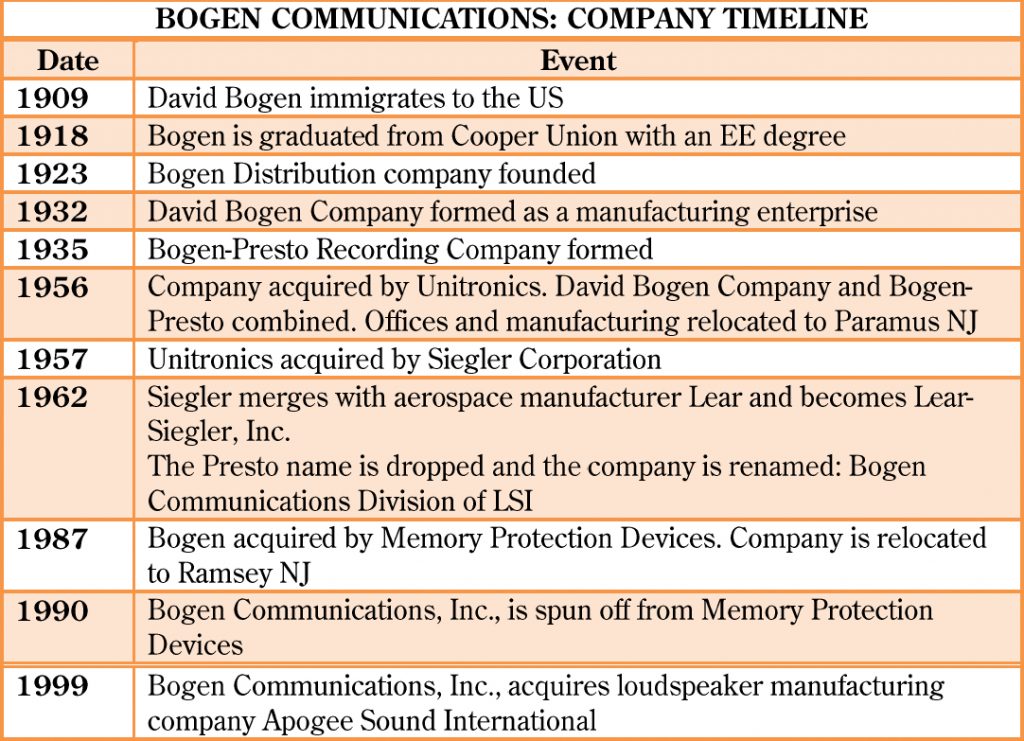

Consequently, by 1955, David Bogen, nearing retirement age with no heir apparent and facing inheritance taxes, elected to sell his company. As can been seen from the accompanying table charting Bogen Communications’ company timeline, after David’s departure, the company passed through several corporate reorganizations.

Today, Bogen Communications, Inc., is a highly respected, multimillion dollar manufacturer of sound and communications products serving the commercial, institutional and fixed installation/touring sound markets. And, it all started with a little guy casting bronze figures of the Statue of Liberty in his modest apartment in Brooklyn NY.

Sidebar: Sidney Harman (1918-2011)

In the early days of the AV industry, various members worked closely together and were mutually involved in the fostering and betterment of the industry. As an illustration of just how tightknit the industry was, we might examine the relationship between the David Bogen Company and industry giant Sidney Harman.

Born in Montreal, Canada, in 1918, Sidney Harman received a degree in physics from City College of New York and, in 1939, took an engineering job in New York with the David Bogen Company, where he helped design public-address systems. After 14 years, Harman was elevated to general manager of the firm.

Harman had a wife, four children and a home in the Forest Hills section of Queens NY. He loved reading, boxing, tennis and music. At night, he liked to play records; he used a transcription turntable borrowed from a radio station, a modified Bogen amplifier and a big tri-axial speaker. Sometimes, Bernard Kardon, chief engineer at Bogen, joined him, and the two cranked up the sound on Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony until the walls rattled.

In 1953, Harman and Kardon gave up their salaries and left Bogen to form their own company, dedicated to producing hi-fi equipment. Each put in $5,000. They set up a plant in lower Manhattan, where they manufactured a line of high-quality amplifiers and receivers for the Radio Shack chain under the name Realist (later changed to Realistic), and then their own line under the name Harman-Kardon.4

Harman-Kardon prospered with the development of the first integrated AM/FM tuner and audio amplifier. In 1969, the company entered the professional audio business with the acquisition of JBL.

References

1 Bogen, Lester, Memoirs of My Father, unpublished family journal

2 Bogen, Lester Ibid

3 Brookman, Jerome, conversations with the author

4 Bacas Harry, Nations Business, October 1988

Acknowledgment: Sincere appreciation is extended to David Bogen’s grandsons, Rich and Michael, for their kind assistance in providing information and duly reviewing (and correcting) this manuscript.

This article was originally published in the March 2010 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.