This month marks the end of my 42nd year working in the audiovisual industry, my entry into which happened largely by accident. (I’ve discussed that topic in previous “AVent Horizon” columns.) This is my ninth year writing for Sound & Communications, and it’s my 32nd year contributing to a long list of industry trade publications (AV, broadcast, cinema, post-production and so on), most of them now just memories.

Having written forecast columns like this one numerous times, I can say one thing with absolute certainty: My predictions are just as likely to be wrong as they are to be right. Trying to figure out where the AV industry is headed can be a very frustrating exercise, particularly when it comes to adoption rates for new tech that pops up in other arenas. “The next big thing” sometimes falls flat on its face when it shows up amid much hoopla at trade shows. More often than not, the products and processes that have the greatest impact on AV typically sneak, largely unnoticed, into the marketplace.

You might not have noticed, but many traditional exhibitors at broadcast-themed trade shows are tracking the continued strong growth in AV; accordingly, they have established a presence—or they have expanded their existing one—at ISE and InfoComm. These folks are a bit ahead of the curve when it comes to transporting AV over networks and deploying video/audio codecs, so it has been interesting for me to see how their sales pitches contrast with our born-and-bred AV nameplates and their largely proprietary solutions.

And the AV industry is strong. Considering the first InfoComm I attended drew barely 10,000 attendees, this year’s final attendance figure of 44,129 is impressive. It shows just how much the industry has grown over the years from its mom-and-pop roots. This past June, I escorted a couple of colleagues from the broadcast and video-production industries around the floor; as first-timers, they were amazed at how large the show was. (One even scored a new job at the show!)

As I dust off the ol’ liquid crystal ball, let’s review the trends we do know about. Then, we can extrapolate how they’ll affect our paychecks next year…and for quite a few years after that.

Displays For AV Will Be More Affordable

My first love has always been display technology. I’ll leave the nuts and bolts of control systems to others, and there are roomfuls of colleagues who are far more knowledgeable about audio and acoustics than I am. But I cut my teeth back in the day by setting up a variety of display products for staging projects and, later on, for fixed exhibits. I attended my first InfoComm (in 1994) as the move from conventional, CRT-based projection to solid-state LCD and then DLP projection was just getting started.

It’s been a truly nutty quarter-century since then. The display-manufacturing business isn’t for the faint of heart. Indeed, entire companies have gone belly up and lost millions of dollars because of sour bets on promising technologies that eventually went south for one reason or another. Remember Ampro, Apollo, Chromatek, Davis and Dukane? How about Fujitsu, Hughes-JVC, Lasergraphics, nView, Proxima, PLUS, Sayett and Sanyo? Remember plasma displays, LCD projection panels, surface-conduction electron-emitter displays (SEDs), rear-projection TVs and light valve projectors? (I rest my case.)

However, I’ve never seen anything resembling today’s business climate. If you had told me 10 years ago that I’d be able to buy a 65-inch “smart” ultra-HD (4K) TV with high-dynamic-range (HDR) support for just $400, I would have laughed in your face. But, indeed, you can. The reasons behind that largely have to do with oversupply of the display panels (mostly LCD) manufactured in Asia for televisions.

Simply put, there is too much manufacturing capacity and there’s not enough demand for these panels. The situation has gotten so bad that one of the largest Chinese display manufacturers recently put a brand new, multi-billion-dollar generation- 10.5 LCD panel “fab” up for sale not long after it opened. With finished LCD panel prices so low, that company would seem to prefer taking a short-term financial hit on its investment rather than having to wade through years of red ink.

If you combine that trend with declining sales of smartphones and tablets, you can see why some long-established brands are slowly shuttering older LCD fabs and putting their research-and-development (R&D) money into direct-view imaging technology that uses inorganic light-emitting diodes (LEDs.) Indeed, LEDs have become the single most disruptive display technology today, wreaking havoc on the large-venue projector market, taking the lead in digital signage, and knocking on the doors of everything from digital cinemas and meeting rooms to home theaters.

Here’s a great example: At this year’s InfoComm, we saw a few demos of “build-it-yourself” fine-pitch LED walls for small meeting rooms. These displays can be assembled by two people in a few hours, hung on a wall or attached to a stationary or mobile stand, and easily connected to a video source through an HDMI port. Granted, they are expensive—some models cost more than $50,000 for a 130-inchdiagonal screen—but they are much brighter than LCD monitors are, they offer very high resolution (depending on pixel pitch) and they support HDR imaging under any ambient-light conditions.

If the past decade is any indicator, then prices for these self-service LED displays could drop by 25 percent or more by next June, particularly given that most LEDtile manufacturing takes place in China and there is plenty of price competition between brands. And, by all accounts, there is a lot of interest in this technology from prospective buyers. The concept is great, and the tech is contemporary enough for any meeting space—even huddle rooms. Look for more AV brands to jump on this conference-room LED-display- wall bandwagon with aggressive pricing—in particular, those marquee names whose bread-and-butter projection business is being hammered by LED displays.

Lurking in the darkness is potentially the biggest market disruptor of all: microLED, which is an imaging technology that creates red, green and blue LED emitters so tiny that they can be used in watches and smartphone screens. As of yet, microLED isn’t ready for prime time—far from it—but a ton of investment capital is going into R&D to make it the next display platform for televisions, mobile devices and even near-to-eye displays.

So, where does that leave the traditional purveyors of large LCD monitors? If they haven’t made the switch to ultra-HD (4K) panels yet, they will have to—and they should do it right quick. Wholesale 4K panel prices in large screen sizes are at rock bottom, with IHS Markit saying earlier this year that the average LCD panel (across all sizes) costs around $500, and it’ll drop to about $300 in three years. And anyway, 4K is king. No one wants to make full-HD display panels anymore—there’s no money in it. As for 8K, the few commercial display products I’ve seen are still too expensive. I don’t expect 8K to have a significant market impact for at least two more years.

Projectors On Endangered-Species List?

Well, are they? No, not quite yet. However, to stay competitive in this market, they have to offer a unique selling proposition beyond lots of lumens. The strongest niche market for projection will be ultra-short-throw installations, where they can hold their own creating 80-inch (and larger) images at affordable prices. The education vertical is still very fond of projectors. And, of course, projection is the only practical way to map images on concave, convex or trapezoidal surfaces without installation challenges and severe image distortion.

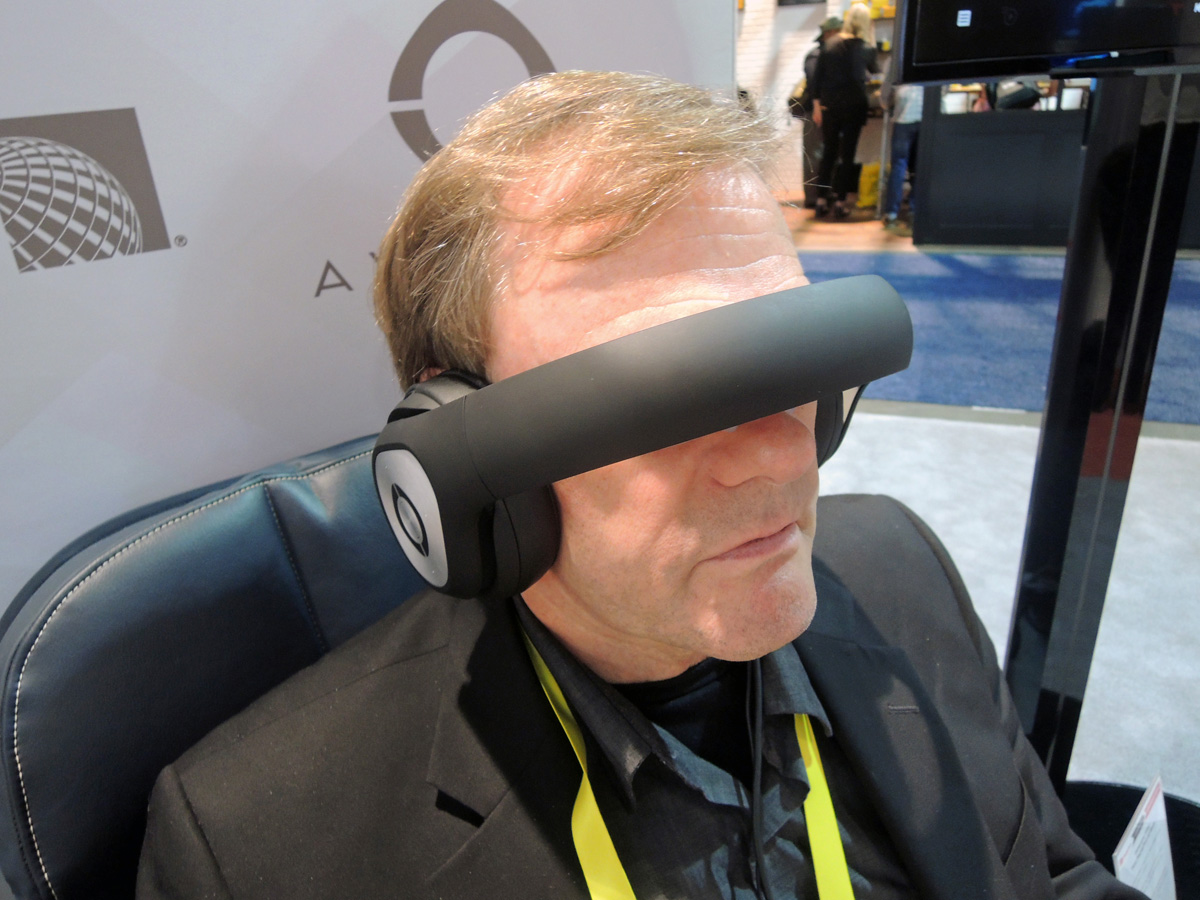

Speaking of near-to-eye displays, 2020 will be another year of sluggish growth for virtual-reality (VR) and augmented-reality (AR) headsets. There’s not a lot of demand for them in our industry, just as there isn’t much demand for them in general. I have more than once described VR as “a solution in search of a problem,” and that appears still to be the case. Current headset designs are too bulky; the near-to-eye resolution is too coarse; and the overall experience for most users is less than favorable.

What we will see more of in 2020 are large, immersive spaces created by curved and warped display screens. It’s easy to wrap organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays around and inside of curved surfaces; indeed, the leading OLED manufacturer will now ship you a tool to bend your own. And I’ve experienced surprisingly effective demos of glasses-free VR standing inside large, half-pipe displays with ultra-HD-resolution, HDR video and three-dimensional spatial sound. Some manufacturers have started to build curved, fine-pitch, inorganic LED tiles and screens, and, of course, it’s easy to use projection mapping to create large virtual spaces.

These environments aren’t just for amusement parks and theme parks, either. In addition, they can be used as teaching tools and for simulations of everything from surgical procedures to deep-oil-field drilling. The requirements will be very high resolution (no screen-door effect allowed!), HDR with a wide, realistic color gamut, and spatial-sound playback to complete the effect. It will be some time before headgear hits those benchmarks, but the ever-decreasing price of large displays can make it happen now.

Let’s move on to control systems. Who will be the first to introduce voice recognition as an AV control interface? (Recall what I wrote earlier about where “the next big thing” often emerges.) If the consumer world is a harbinger, we’ll be using more and more speech-recognition technology to operate AV gear and facilities. It’s just a matter of time.

Voice-recognition systems are already a mainstay in the home; for that reason, it shouldn’t be too much of a challenge to migrate them to AV control systems that incorporate some degree of artificial intelligence (AI). Speech-recognition chips are quite good at distinguishing between languages, regional accents and voice pitches. Can these systems replace a touchpad control? There’s no reason why not.

The groundbreaker surely won’t be one of our industry’s established control companies, as they have too much invested in making and supporting existing interfaces. No, I think it will be a smaller company—perhaps even a startup at a small trade-show table—that will advocate for and demonstrate a practical voice-control system for AV. And, if the system actually works, you can be sure one of the larger players will buy the company out. I’m pretty sure you’ll see such a demo at ISE or InfoComm next year.

Speaking of control and signal distribution, the AV-over-IP format battles continue unabated. In this corner, we have a proprietary, turnkey AV/IT system incorporating light video and audio compression, signal transport and metadata that’s been getting a lot of press coverage lately. In the other corner, we have AV/IT systems based on low-latency wavelet codecs that are more in line with what other industries, like broadcast and cinema, use. Which is the right way to go?

The key to choosing an AV-over-IP platform will be futureproofing. Right now, our industry seems to be fixated on how we can get 4K video through a 10Gb network switch, which is kind of a low bar with 8K video and bitrate boosters like HDR and high-frame-rate (HFR) video coming into play soon. The proprietary AV-over-IP system has a limitation of low compression ratios, whereas codecs that originate in the broadcast and cinema worlds are capable of much higher ratios. How much? Enough to pack down an 8K video signal with 10-bit 4:2:2 color, refreshed at 120Hz, with minimal latency. (Yes, I did say that 8K wouldn’t be a big market driver for a while; it’ll get here eventually, though.)

Imagine pushing a 4K signal with 10-bit 4:2:2 video, with a 120Hz frame rate, through that same 10Gb switch: The uncompressed data rate of 28.5Gb/s might be a bit strenuous for that turnkey system to handle. By contrast, a JPEG XS codec could do it without breaking a sweat.

It is possible right now to buy a 40Gb switch, although current product offerings use four 10Gb ports simultaneously with timing protocols. (We interfaced 4K video the same way in the early days, using four HDMI 1.4 ports and stitching together four 1080p images.) One broadcast-equipment manufacturer has pushed for a 25Gb “mezzanine” format, whereas a startup claims to be working on 50Gb and 100Gb switch fabrics. In 2020, I expect to see single-port network switches capable of speeds that exceed 10Gb/s at major trade shows.

Wireless networking will be just as important as—if not more important than—wired switches. We already have a fast wireless IP protocol, 802.11ax, which is beginning to make its way into wireless access points (WAPs). Forget 5G for now—there’s still way more hype than reality attached to it. The simple fact is this: Unless you use millimeter-wave frequencies for 5G wireless links, your download speeds won’t be substantially faster than what we have now with 4G. In addition, 5G networks will require many more nodes, due to the short range of millimeter-wave radio signals. For the average presenter, in-room 802.11ax will do the job of sharing photos and streaming videos nicely.

It’s possible the time has come. Our industry has a reputation for being a hoarder when it comes to old technologies, and the RS232 format celebrates its 58th birthday next year. Can you think of any tech that old that we still use, aside from LEDs? I am starting to see more AV products dropping the nine-pin D-sub connector in favor of an RJ-45 network jack that, in some cases, does double duty as an HDBaseT connection. (For what it’s worth, the latter format is likely headed to extinction, as more people get with the AV-over-IP program.)

And, finally, we turn to the elephant in the room. Low-cost manufacturing (increasingly enabled by robotics) and aggressive pricing aren’t limited to the display supply chain. Every piece of AV hardware that we use can be made cheaper by someone else, and more and more of it moves through distribution with each passing year. I’ve even heard multiple stories of customers buying two or more of a given product at discounted prices, then simply replacing units that have malfunctioned and would otherwise need repair.

That’s why you see so many smaller booths at trade shows these days. The established players just can’t justify big trade-show budgets the way they used to. Not with so many products selling with two or three zeros on their price tags. And there are plenty of smaller booths featuring startup companies that see opportunities in selling new tech, such as fiberoptic-based signal extenders, network switches with display interfaces built in, cutting-edge control systems and low-cost wireless-presentation-sharing gadgets. And software—lots of software—mostly for control systems, but also for analytics like who’s using the facilities and when.

So, there you have it. Cheaper displays (and AV hardware), fine-pitch LED displays for meeting rooms, large VR space designs, the emergence of voice-recognition technologies for control, more migration to AV-over-IP, faster network switches and wireless, and the continuing commoditization of hardware. See you next December (unless, by then, I’m replaced by a robot)….