Charles Paul Boner (1900-1979) was born in the small north Texas town of Nocona (Montague County), the son of Charles Wilburn and Sallie Lee (Westmoreland) Boner. His father was a publisher and editor of various local newspapers in several surrounding communities. In some of C.P. Boner’s early writings, he recalls that, at the age of 14, he became a “printer’s devil” for his father’s Nocona News. Inasmuch as the family name was Boner, and Nocona is a community with a rich heritage of German farmers, it is likely that his ancestors emigrated to north Texas from pre-Bismarck Germany during the early days of the Texas Republic.

Musical Heritage

Young Boner took to music at an early age, and he recalled in a paper presented to the Cap & Gown Society of Austin how he, his uncle and several cousins would gather frequently to stage impromptu musical interludes for their immediate families. He himself toyed with learning the cornet and violin before turning to the piano when he was 12. He encountered his first pipe organ in 1916, prompting a lifelong musical love affair. Indeed, it was Boner’s interest in pipe organs that fostered his later investigations into audio equalization or, in his term, “room tuning”—an outgrowth of the analogy between tuning an audio system and tuning a pipe-organ to a room, both of which employ similar practices.

At one point, during Boner’s time at the University of Texas’ Physics Department, he and graduate student Robert Newman—later to be one of the principals at Bolt Beranek & Newman (BB&N)—collaborated on constructing a pipe organ out of parts gathered from at least three sources. Boner commented, “This taught us a good deal about the inner workings of a pipe organ and the physics involved.” The conglomeration in its final form consisted of a four-manual, 1800-pipe and 169-stop device. It was driven by a 12-horsepower blower, with wind pressure of 5” to 15” water gauge. As a result of this project, the university was out about $3000; however, the instrument served the Physics Lab and various radio-media outlets for about 20 years.

It was Boner’s interest in pipe organs that fostered his later investigations into audio equalization or, in his term, “room tuning.”

Boner was a sufficiently talented musician to become the resident organist for the First Baptist Church in Austin for many years. Additionally, during his college days, he along with the resurrected four-manual organ was frequently featured on the UT campus radio station. With Boner at the console, player and instrument were also regular entertainers on the Southwest Network’s weekly “Organ Reveries,” providing a program of organ interludes. On a lighter note, Tim Thomas Sr., a friend of Boner’s from Fort Worth, confided that “Doc” (a nickname for Boner used by his close friends1) once told him, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, that he (meaning Boner) was probably the only acoustical consultant of record that could boast, or admit, to having earned a living playing a piano in a bordello.

Boner In Academia

At age 16, Boner was accepted for enrollment at the University of Texas in Austin. He accomplished the rare feat of serving at every position in the University organization from freshman through attainment of his PhD (with a year out to serve in World War I). In 1920, he received his BA in Physics followed by an MA in Physics in 1922. From 1927 until 1928, he did his graduate studies as a Whiting Fellow at Harvard University; he then returned to UT to acquire his PhD in Physics. Foretelling his future investigations, his doctoral thesis published in June 1929 was entitled, “The Measurement of Capacitance and Inductance in terms of Frequency and Resistance at RF.”

During the 1930s, Dr. Boner served as professor of physics at UT and was appointed chairman of the department in the late 1930s. He took a hiatus from his beloved UT to serve during World War II as associate director under Frederick Vinton Hunt at the Harvard Underwater Sound Labs. He played a significant role in that position, developing advanced sonar devices and the acoustical torpedo. For his contributions to the war effort, he received the Naval Ordnance Medal and joint Army-Navy Certificate of Appreciation.

Boner served during World War II as associate director under Frederick Vinton Hunt at the Harvard Underwater Sound Labs, where he was involved in developing advanced sonar devices and the acoustical torpedo.

Returning to the 40 acres, as UT is often fondly referred to, in 1945, Boner set about forming the Defense Research Laboratories and served as its director from 1945 to 1965. His academic credentials were further enhanced when, in 1949, he was appointed dean of the College of Arts and Sciences—a position he held until 1954. In 1953, he also assumed the role as dean of the University, and simultaneously served as vice president of Academic Affairs from 1954 to 1957. During the ‘60s, Boner began a gradual process of transition and retirement from university life.

Early Projects

Boner developed an early interest in acoustical and electro-acoustical matters. His first published paper in 1922 was on the subject of “Good and Bad Acoustics: 550BC to the Present”. Working under Professor S.L. Brown of UT’s Physics Department in the 1920s, Boner helped build and operate the campus radio station (KUT) and designed and built the first large-scale public-address system for use at Memorial Stadium. This PA system was, at the time, one of the most powerful systems in the US; sound was broadcast through three groups of megaphones (horn loudspeakers), each measuring 10’x10’. Each of the sizeable horns was driven by four loudspeakers using 120 watts of power.

Boner’s wide-ranging interests also lead him into investigations of radio broadcast studio design, and he was commissioned the design of WFAA-KGKO Studios atop the Santa Fe Building in downtown Fort Worth. Also, during the early 1940s, Boner served as the acoustical consultant for the new University of Texas Music Building. Collaborating with renowned Dallas-based architect George Dahl and Dr. E.W. Doty, chairman of the UT’s Department of Music, the design team produced a facility that was unique for its time. This radical design was among the first “modern” music buildings in the country to employ angled walls, acoustical diffusion and spring-isolated floors, walls and ceilings.

“Doc” developed an early reputation as an iconoclast who suffered fools poorly. The reports of his witticisms and wry comments came to be known throughout the sound and communications industry as “Bonerisms.”

“Doc” developed an early reputation as an iconoclast who suffered fools poorly. The reports of his witticisms and wry comments came to be known throughout the sound and communications industry as “Bonerisms,” and would constitute a book unto themselves. His son, Charles Boner, was once asked whether these widely attributed comments were indeed true or whether they were merely the stuff of myth and legend. Harking back to his father’s early days, Charles related the following tale, which he swears is factual:

“During the 1930s, Doc was teaching Physics at UT and had gained some degree of reputation as being knowledgeable in the area of acoustics. At the same time, the Texas State Democratic Convention was slated to hold its annual convention in Austin. The only building of sufficient capacity was the old Memorial Auditorium alongside the banks of the Colorado River downtown. This was a Quonset-type structure, with tin roof, concrete floor, concrete risers and a reverberation time that could be measured by using a calendar.

“Doc inspected the building and inquired about ‘how much time do we have to correct these deficiencies?’ ‘About a week,’ he was advised. With this information, he offered the following advice that he allowed they would not be particularly pleased with:

“His suggested solution was to gather up as many truckloads of fresh cow manure as possible and spread it as deeply and uniformly as possible on the auditorium floor. He cautioned that the manure would have to be as ‘fresh’ as possible because dried manure would not be sufficiently absorptive.

“The Texas Democratic Convention sponsors duly laid several layers of manure on the convention hall floor—for what must have been a truly ‘stinky’ convention.

Doc later commented, ‘That’s about what the Democrats deserved.’”

Dawn Of Equalization

The concept of equalizing an audio system for improved sound-system response was introduced by John Volkman at RCA in the early days of cinema sound. It was an acknowledged observation that sound tracks from those days (late 1920 to early 1930) were rather dismal. Volkman’s work in variable audio equalizers was adopted quickly by the film studios for enhancement purposes in post-production. Companies such as Langevin and Cinema Engineering stepped forward with variable equalizers to meet the cinema industry’s needs. Several of these designs were quite innovative. However, there were no recorded instances of such devices being employed in room-equalization processes.

Boner came to the conclusion that feedback occurs as a sine wave at one precise frequency. Hence, he reasoned, to eliminate the feedback one need only insert very narrowband notch filters to stifle the offending frequencies.

Employment of equalization in architectural acoustical spaces languished until the late 1950s. The problem of feedback from electro-acoustical systems was a recognized problem, but little effort was being undertaken to resolve what was becoming an increasing distraction in sound-reinforcement systems. The general term for systems of the day was “Public Address—PA,” and any attempt at reproducing quality speech or musical transmission was pretty much deemed useless or totally unobtainable.

Feedback as we now know it is created when unity gain and in phase conditions exist between an active microphone(s) and the associated loudspeakers within a given architectural space. This particular phenomenon, of course, was not evident in cinema or recorded playback systems; hence, it did not attract the attention of the cinema or recording studio/playback members of the audio industry.

‘Good’ Natural Acoustics

Likewise, the acoustical consultants of the period were somewhat disdainful of electro-acoustical systems and placed their primary efforts at designing spaces with “good” natural acoustics. The only solution to eliminating feedback in difficult spaces was to turn the system gain down, sometimes to the point where the entire system was inaudible.

In 1958, Dr. Wayne Rudmose from Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas employed some then-theoretical ideas to create a rudimentary electro-acoustic equalization for a new sound system at Dallas’ Love Field Airport. When he published his paper, it created quite a stir in the world of both academic and real-world practitioners.

Boner and Rudmose were longtime friends and academic colleagues. In fact, they collaborated on authoring a paper in 1938 for the Acoustical Society of America Journal. Doc’s interest was piqued, and he set about looking for a practical method to reduce feedback in electro-acoustic systems.

In practice, Boner would raise the gain of the sound system under investigation until it reached the point of feedback; he would then adjust a beat-frequency audio oscillator to reach a null.

Charles Boner relates how, during about this same timeframe, he wandered into his father’s workshop where he was driving nails into a large sheet of plywood and wrapping the nails with turns of wire. Charles said, “I watched him with interest for a few minutes and finally asked what he was building.” Doc responded with a single-word answer: “Filters.” Utterly baffled, the 16-year old Charles turned on his heels to leave his father to his mysterious pursuits.

From his years of pursuing the physics of pipe organs and his experience in acoustics, the man who was subsequently dubbed “The Father of Architectural Acoustic Equalization” came to the conclusion that feedback occurs as a sine wave at one precise frequency. Hence, he reasoned, to eliminate the feedback one need only insert very narrowband notch filters to stifle the offending frequencies. Unfortunately, there were no commercially available LRC networks that could be used for such purposes, and Boner had to build his own filters (which returns us to the younger Boner’s confusion as he watched his father laboriously winding his own home-brewed inductors).

Today, we have the notion that the parametric filter was spawned in the age of DSP; however, in essence, these initial filters were true parametrics. In practice, Boner’s broad-band parametric filters were used to tailor the overall frequency response.

Boner quickly became disillusioned with the idea of hand building inductors and approached a former student who was manufacturing precision filters for instrumentation. Boner described what he was looking for in the way of inductors with which he could implement his narrow-band equalization procedures. Gifford White agreed to supply him with such devices, a move that subsequently launched Austin-based White Instrument Company into the new field of acoustical equalization.

The next bridge to be crossed was the need to identify the offending feedback modes and then “tune” the system by inserting extremely precise narrowband filters to stifle the offending frequencies while, at the same time, not have too much of a detrimental effect on the system’s frequency response, e.g., tonal content.

Eliminating Feedback

At the time, instrumentation for implementing this “seek and destroy” method of eliminating offending feedback modes was essentially non-existent. In practice, Boner would raise the gain of the sound system under investigation until it reached the point of feedback; he would then adjust a beat-frequency audio oscillator to reach a null. When Richard Boner, another son of the founder and currently a principal of BAI, was asked why an oscilloscope wasn’t used to identify amplitude and phase, he responded, “Frankly, by using one’s ear, the point where the system was nearing feedback was readily noticeable. Thus, the ‘by-the-ear’ method was quicker, the sine-wave oscillator provided the reference for the feedback point and it alleviated the need to haul around one more piece of test equipment.”

Once the offending frequency was identified, Boner would then either calculate or use a capacitance decade box to construct an RLC filter tuned to the frequency of interest. The actual physical filter then would be fabricated using a White Instrument inductor, a precision capacitor and a value of resistance chosen for the degree of attenuation and the skirt slope characteristics desired.

Parametric Precursor

Central to the process were the unique White Instrument tapped toroidal coils. By varying the taps that were provided at 640mH, 160mH and 16mH, it was possible to tune any bandwidth and the associated filter depth by using this passive filter design. Today, we have the notion that the parametric filter was spawned in the age of DSP; however, in essence, these initial filters were true parametrics. In practice, Boner’s broad-band parametric filters were used to tailor the overall frequency response.

Current equalization practices closely follow the same procedures pioneered by Boner back in the early 1960s. We are still doing the same thing, albeit with digital processing rather than passive RLC networks.

Once the broad-band curve was sufficiently flattened, then narrow-band parametrics were introduced for specific feedback control. Indeed, current equalization practices closely follow the same procedures pioneered by Boner back in the early 1960s. So, 40 years later, we are still doing the same thing, albeit with digital processing rather than passive RLC networks.

‘Cut-And-Try’

If the reader envisions this as a somewhat “cut-and-try” procedure, it was indeed a combination of physical science and an artistically dependent analysis of what constituted acceptable tonal considerations.

Inasmuch, for any given system, there is more than one ring-mode, each of slightly lower amplitude than the preceding one, the procedure was repeated for each succeeding offending frequency until the introduction of yet another filter reached a point of diminishing return. Doc laughingly remarked on occasions that the procedure reached a terminal point “when I ran out of time, the client ran out of money, we found ourselves fighting for minute fractions of a dB improvement or a combination thereof.” Using this technique, a sound system could be corrected to achieve an improved gain before feedback of 6dB or greater.

Boner’s work certainly drew the admiration of his contemporary fellow acoustical consulting colleagues. However, time considerations and required artistic content for implementing the process drew some criticism.

Although certainly effective, the procedure was a time-consuming exercise; it was not uncommon for the implementation to require several days (and nights) of onsite efforts. Boner’s work certainly drew the admiration of his contemporary fellow acoustical consulting colleagues. However, time considerations and required artistic content for implementing the process drew some criticism. As long as it was just Doc sitting alone in a darkened auditorium at three o’clock in the morning and with some degree of financial independence by virtue of his “day-job,” the procedure was viable. An examination of some of his early invoices gives evidence that he gathered more satisfaction from a successful implementation than any financial rewards.

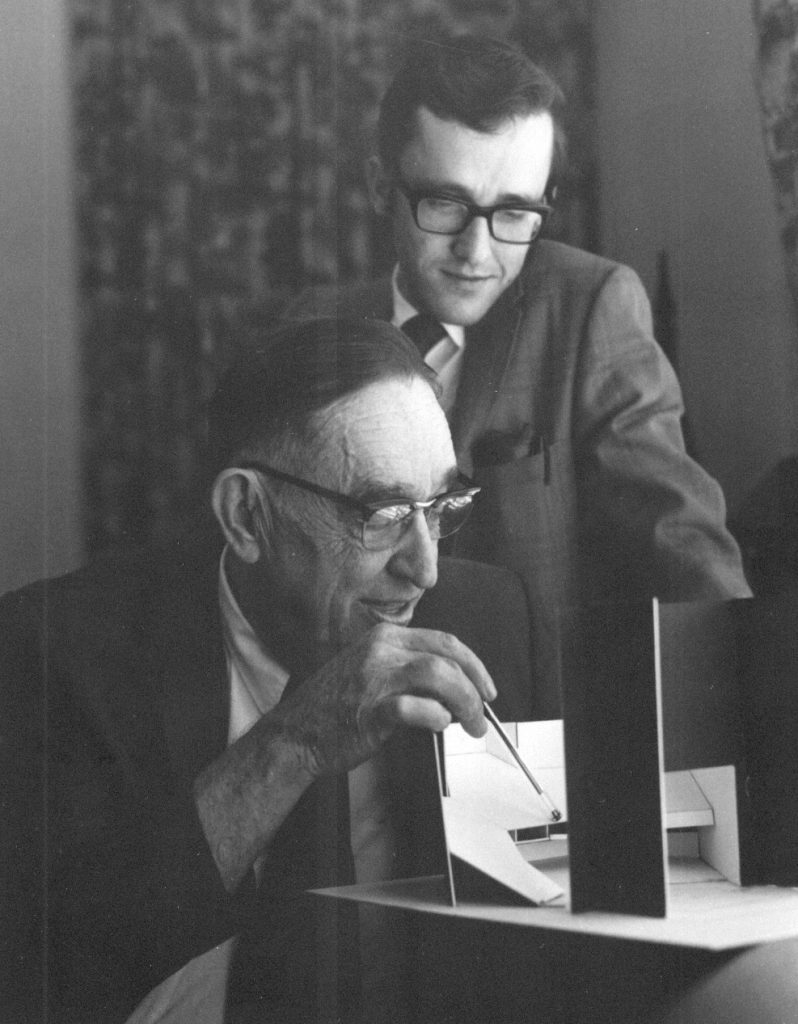

Boner Associates Acoustical Consulting

In 1960, with his University responsibilities winding down, Boner turned increasing attention to the development of his independent acoustical consulting practice, which he had originally founded in 1935. Boner Associates quickly attracted the attention of clients searching for solutions to sound-system deficiencies. Although there was some degree of work involving system design for new buildings, most commissions were remedial in nature; that is, the client, in the form of an architect or end-user (or both), found himself with a glorious new structure in which the sound system was (a) marginally usable or (b) totally ineffective.

In 1960, Boner turned increasing attention to the development of his independent acoustical consulting practice, which he had originally founded in 1935. Boner Associates quickly attracted the attention of clients searching for solutions to sound-system deficiencies.

An early example of (b) was a newly constructed auditorium in Wichita Falls TX. Today we would probably be inclined to term the project a “Theater for the Performing Arts;” however, the term in vogue at the time was “Municipal Auditorium.” Designed by the local A&E firm of Pardue, Read & Dice and installed by local sound contractor George Newton, the facility, when opened, had some serious acoustical deficiencies.

Newton turned in desperation to Jack Frazier of Frazier Loudspeaker Company in Dallas, who had manufactured the speakers for the job. Frazier was a friend of Boner and contacted Doc for some help. Doc gathered up his battered briefcase and a collection of parts and caught a train for Wichita Falls.

Boner, Frazier and Newton gave their utmost attention to turning a sow’s ear into a silk purse. That they were successful is witnessed in a letter of appreciation from Don Read of the Architect’s office dated October 5, 1964, saying in part, “Mr. Van Cliburn even went on to say that this auditorium was among the three best he had ever appeared in.”

An example of a project in which Boner was involved from the design stage through final commissioning was the new Dallas Arena, a building that to this day is still a part of the Dallas Convention Center. A domed, round room with severely raked seating, it had all the makings of an acoustical disaster. Due to diligence and pre-planning, however, it was given rave reviews for its acoustical excellence in the local Dallas newspapers.

With his reputation firmly established and his salty remarks becoming legendary, Boner was sought out for increasingly more prestige commissions. BB&N had undertaken the sound-system design for the new AstroDome in Houston—at the time, the largest domed stadium in the world. Though equipped with the latest concepts of sound-reinforcement equipment, the project was deemed horribly deficient in sound reproduction. The call went out for Boner. Using his narrow-band, onsite-constructed RLC networks, and after literally days upon days of implementation, the sound system finally was proclaimed as being usable.

Licensing And Marketing Boner’s IP

Boner did take steps to patent his procedures. However, as so many before him, he learned that a patent for a procedure is difficult to defend. Initially, Boner sought to license others as practitioners; this proved mildly successful, as people like Robert Coffeen in Kansas City and various sound contractors signed on as Boner devotees. However, in many cases, these licensees primarily were agents who solicited projects and left the final implementation in Boner’s hands.

BB&N explored the process, but after visiting an implementation procedure, Dr. Leo Beranek commented, “The process is too time consuming and tedious for economic consideration.” David Klepper, then with BB&N and later a principal at the acoustical consulting firm of Klepper, Marshall, King, saw merit in the process and employed Boner for several projects. Herschel Fentriss, who operated a sound-contracting firm in Oklahoma City, was a solid Boner proponent; a fact that goes a long way in explaining the proliferation of churches and meeting spaces in Oklahoma that were equipped with Boner equalization panels.

Boner contributed enormously to the realm of knowledge surrounding audio equalization, and there is little doubt that his efforts spawned developments that are now considered commonplace in sound-reinforcement practices.

Among the manufacturing entities, the only known firm other than White Instruments to seek an arrangement with Boner was Anaheim CA-based Altec Lansing Corp. Depending on whose story you choose to believe and under what circumstances the events unfolded, Altec Lansing sensed an opportunity to further develop the Boner procedure as a means to augment its sales of sound equipment. Again, the specter of long, tedious implementation, the need for artistic considerations and the need for training a cadre of practitioners stood in the way of producing manufacturable products.

Considering that Art Davis, previously with Cinema Engineering and Langevin, was by then on staff at Altec Lansing, a concerted effort on Altec’s behalf resulted in a 1/3-octave “broad-band” procedure, using more easily implemented instrumentation packages and tempered with narrow-band tuning. Altec Lansing introduced its procedure under the trade name “Acousta-Voicing.”

Doc Boner saw this as a blatant intrusion on his patents and an infringement on the aura of trust in which he had approached the arrangement. Talk of impending litigation was rampant; however, Boner was not a particularly litigious individual, and eventually the rift was by-and-large mitigated. Nonetheless, there remained an aura of animosity between the two parties even to the time of Boner’s death.

Boner In Tribute

Certainly, Boner contributed enormously to the realm of knowledge surrounding audio equalization, and there is little doubt that his efforts spawned developments that are now considered commonplace in sound-reinforcement practices.

Boner was honored over the years as chairman of the Executive Council of the Acoustical Society of America (1947-1950), president of the ASA (1963) and a Fellow of the Audio Engineering Society.

C.P. “Doc” Boner died on April 12, 1979. In a parting resolution signed by the president of the University of Texas and representatives of the general faculty, the proclamation stated: “Dr. Boner was lauded as a mentor who will be mourned by his family and all who had the benefit of his friendship, encouragement and assistance.”

The firm he founded in 1935, Boner Associates, continues to provide services under the direction of sons Charles and Richard, respectfully utilizing the name BAI Acoustical Consultants.

References

- C.P. Boner avoided the use of his first name, “Charles,” and preferred to use his middle name, “Paul.” In his correspondence, he generally used the signature “CP Boner.” His correspondents generally addressed him as Paul. Verbally, his friends and colleagues referred to him as “Doc,” a term he embraced with grateful appreciation.

This article was originally published in the April 2004 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.