Emile Berliner1 (1851-1929) was lauded by President Herbert Hoover as “an inventive genius.” The US Supreme Court confirmed him as the true inventor of mechanisms claimed by Bell, Edison and others. His inventions are integral to every home, industry and institution. The telephone, record player, helicopter, radio, microphone, transformer, acoustic tiles and other important innovations owe their development to Berliner, and his activity in public health saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of children, yet Emile Berliner is absent from America’s schoolbooks and the public consciousness.2

The Early Years

Berliner was born on May 20, 1851, in the Hannover-Neustadt region of Germany, the fourth-oldest of 13 children born to Samuel Berliner and his wife, née Sarah [Sally] Friedman. The first known mention of the family dates their ancestry to the 1770s, when Emile’s paternal great-grandfather Jokew (Jacob) Berlin settled in the area.3 The family name denotes that they heralded from Berlin; when permanent names became required of Hannover Jews, Jacob’s son, Moses, changed the family name to Berliner.

Prior to the Napoleonic era, Jews were prohibited from belonging to a craft or business guild, and the Berliner family lived in dire poverty. After the laws were somewhat liberalized, Moses (Emile’s grandfather) started a modestly successful “cut and yard-goods business.” The third-generation Samuel Berliner (Emile’s father) was a manufacturer of linen goods and a Talmudic scholar, while his brother Meyer was in the business of dyeing and washing silk and wool fabrics. Though still a family of modest means, the Berliners were a pious, charitable family that wholeheartedly participated in the life of the Hannover Jewish Community.

The telephone, record player, helicopter, radio, microphone, transformer, acoustic tiles and other important innovations owe their development to Berliner.

Several of Emile’s older brothers were conscripted into the military, and Samuel found it difficult to support his wife and their 11 surviving children. Hence, the 14-year-old Emile was obliged to quit his schooling at the Samsonshule in Wolfenbüttel and set to an apprenticeship, first in a printing house and then, according to some sources4, at age 16, as a clerk at a Kravattengeschaft (tie manufacturing plant). During this episode in his young life, Emile’s inventive genius surfaced when, after investigating the production of the fabrics, he constructed a more efficient power loom. “Experts…expressed astonishment that an adolescent youth, unaided and without technical equipment, could have devised so practical a mechanism.”5

An Offer He Couldn’t Refuse

In 1866, a family friend named Nathan Gotthelf, who had immigrated to the United States previously and became the proprietor of a dry-goods store in Washington DC, visited with the Berliners. Hannover had once again come under the control of the militaristic Prussian regime; Jews were again being subjected to severe repression, and young Emile was facing the uncomfortable prospect of being conscripted into the military for service in the Franco-Prussian War. On the occasion of Herr Gotthelf’s subsequent visit to Germany in 1869, he offered Emile a job at his store in Washington DC—an offer that was gratefully accepted.

Berliner somehow found the time and money to study the piano and violin, and he expanded his knowledge of electricity and physics on a part-time basis at the Cooper Institute (now Cooper Union).

The family scraped together enough money so that, by 1870, the 19-year-old Emile could book passage to the United States. After the financial panic of 1873, times were tough in the US, and unemployment was rampant. For the next few years, Berliner, having returned to New York, held a variety of positions, including selling glue, selling haberdashery for a firm based in Milwaukee, painting backgrounds for enlarged tin-type portraits and giving German lessons.

Eventually, he found gainful employment as a cleanup man at the Constantine Fahlberg Laboratory, where his interest in scientific experimentation was piqued. Remarkably, during this time period, Berliner somehow found the time and money to study the piano and violin, and he expanded his knowledge of electricity and physics on a part-time basis at the Cooper Institute (now Cooper Union). Like so many other youthful would-be inventors of the time, Berliner was fascinated by the prospect of converting sound into electrical impulses that could be transmitted over wires.

Improved Telephone Transmitter

Whatever the circumstances, 1876 found Berliner back in Washington again, clerking for Gotthelf & Behrend (by then The Behrend and Company). Obsessed with a desire to excel in science, research and invention, which he considered his destiny, Berliner continued to carry on his electrical experiments in the sanctity of his quarters in a boarding house. The year 1876 was also the occasion of the American Centennial Celebrations in Philadelphia—events that Berliner attended. This provided him with the opportunity to examine Alexander Graham Bell’s newly developed telephone. Although enthused by the prospects of this new instrument, Berliner, along with several others, noted that, although the receiver seemingly was acceptable, the transmitter was of poor quality, and the distance over which satisfactory audio levels could be sustained were limited severely.

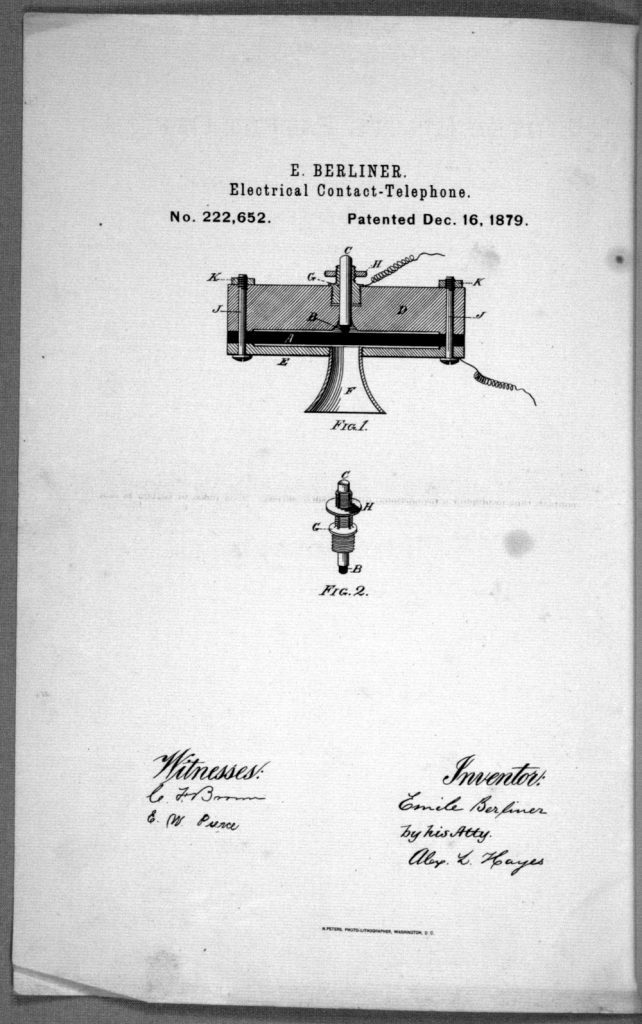

Berliner acquired a telegraph instrument and, after some experimentation, set about to construct an improved telephone transmitter. His efforts culminated in the carbon button, variable-pressure contact transmitter/microphone.

Taking a cue from a comment passed to him by a telegrapher, “that more current flows as one presses harder on the key,” Berliner acquired a telegraph instrument and, after some experimentation, set about to construct an improved telephone transmitter. His efforts culminated in the carbon button, variable-pressure contact transmitter/microphone. He reasoned that, by varying the current flow as a condition of the sound pressure applied to the diaphragm, the audible sound could be transformed successfully into electrical impulses suitable for transmission.

Invention Of The Microphone

Wile noted, “Early in April of 1877, Berliner made an iron diaphragm transmitter by knocking out the bottom of a soap box. He then nailed on in place of the bottom a piece of sheet-iron and placed a cross-bar across the middle of the box. A common screw, passing through this cross-bar, touched the center of the diaphragm…He tried it with a galvanometer and found that the current varied greatly with the variation of [sound] pressure [applied to the diaphragm].”6

History is silent about what inspired Berliner to introduce an induction coil into his apparatus but, in what might have been the first example of impedance matching (although not probably recognized in those terms), this transformed Bell’s telephone from a curious toy into a practical communication device that could be employed over considerable distances. When the management of the newly formed American Bell Telephone Company became aware that a young and unknown man in Washington had filed a caveat on April 4, 18777 with the US Patent Office covering the new transmitter, they were dumbfounded.8 To prove the viability of Berliner’s new device, a demonstration before Professor Joseph Henry, who by then was the head of the Smithsonian Institution, was arranged. The National Republican of Washington DC reported on October 2, 1877:

“Yesterday afternoon there was a very interesting exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution before Professor Henry of a number of discoveries and inventions of Mr. E. Berliner of this city. The invention(s) consisted of improved apparatus and modes of electric communication. The first instrument exhibited was the ‘contact telephone’ for transmitting sound vibrations from plate to plate, so as to enable persons to communicate. The second was the ‘electric spark telephone’ which produced the same result by another process, that of the transmission of a spark. The third instrument was a ‘telephonic transfer’ designed for transmitting sound by changes in the intensity of the circuit.”

Patent Approved

Berliner’s patent for his transformer was approved on January 15, 1878. Thus, the two critical elements of the device we now call the telephone—the microphone and the transformer—were established as the invention of Emile Berliner. Eventually this determination was confirmed by the US Supreme Court.

Berliner’s patent for his transformer was approved on January 15, 1878. Thus, the two critical elements of the device we now call the telephone—the microphone and the transformer—were established as the invention of Emile Berliner.

The Bell transmitter was knowingly deficient, and Berliner, knowing that his device would make telephony viable, offered to sell the use of his devices to Bell Company of New York. With typical attorney arrogance, Bell’s lawyer wrote on January 22, 1878: “I do not suppose that you seriously believe that your invention is worth $12,000 at the present time.”9 Finally, in September 1878, Thomas A. Watson, representing Alexander Graham Bell, commenced negotiating for the rights to use Berliner’s devices by the Bell Telephone Company. Reportedly, Bell Telephone of Boston offered $50,000 for the rights to use Berliner’s patents—plus a well-salaried position as a research assistant with the company.10,11

Berliner remained in active service with the Bell Telephone Companies for the next seven years, with offices first in New York and later in Boston. The year 1881 was a busy one for Berliner: He became an American citizen, married a young woman of German descent named Cora Adler, and briefly returned to Germany where, along with his brothers Joseph and Jacob, formed the Telephon-Fabrik Berliner with branches in Vienna, Berlin, Budapest, London and Paris.12 In 1886, Berliner chose to pursue his cherished dream of becoming an independent private researcher and inventor. He resigned from the Bell Telephone Company, and he and Cora left Boston to set up housekeeping in a home on Columbia Street, in Washington DC.

Mechanical Reproduction Of Sound

Allow us to destroy yet another myth: Thomas Alva Edison did not invent the phonograph. That distinction belongs to the Frenchman Leon Scott who, as early as 1855, incised a sound-actuated spiral groove on a revolving cylinder. He called his mechanism a “phonautograph.” It was marketed in 1859 for scientific sound-analysis purposes. Edison had an instrument built duplicating Scott’s device, renamed the machine a “tin-foil phonograph,” and recorded his famous recitation of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Whereas Scott had never patented his device, Edison was savvy enough to patent his “new invention” in 1878; he then founded the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company, took credit for inventing the phonograph and began marketing his latest “wonder.”

Berliner set out to invent new recording materials, develop entirely new principles of recording and produce new instruments that would be capable of the accurate playback of musical sounds.

Not to be outdone by his arch-rival, Bell and Bell Laboratories entered the competition for a mechanical sound reproducer and assigned the development of such a machine to Chinchester A. Bell (Alexander Graham’s cousin) and Charles Sumner Tainter. A model was produced in 1881 and offered to Edison, who rebuffed the idea. The Bell instrument had several significant improvements over the earlier crude Edison device, including a spring-wound mechanism, a more durable wax cylinder and a longer playing time. It was put to market as a “graphophone” in 1887. Edison, in turn, “ripped off” the graphophone with his improved phonograph, as both parties strove to market their devices to a nonexistent office sound-recording dictation need.

Both Bell’s and Edison’s machines were dismal failures in the office recording market, and neither could create any reasonable accurate reproduction of music. That both might well have disappeared into historical footnotes would have been a reasonable conclusion had not an investor named J.H. Lippincott bought out both firms, founded the Columbia Phonograph Company and sold the devices as jukebox curiosities. To complete the circle, when Lippincott later became paralyzed, Edison bought the then-moribund Columbia Phonograph Company in 1890.13

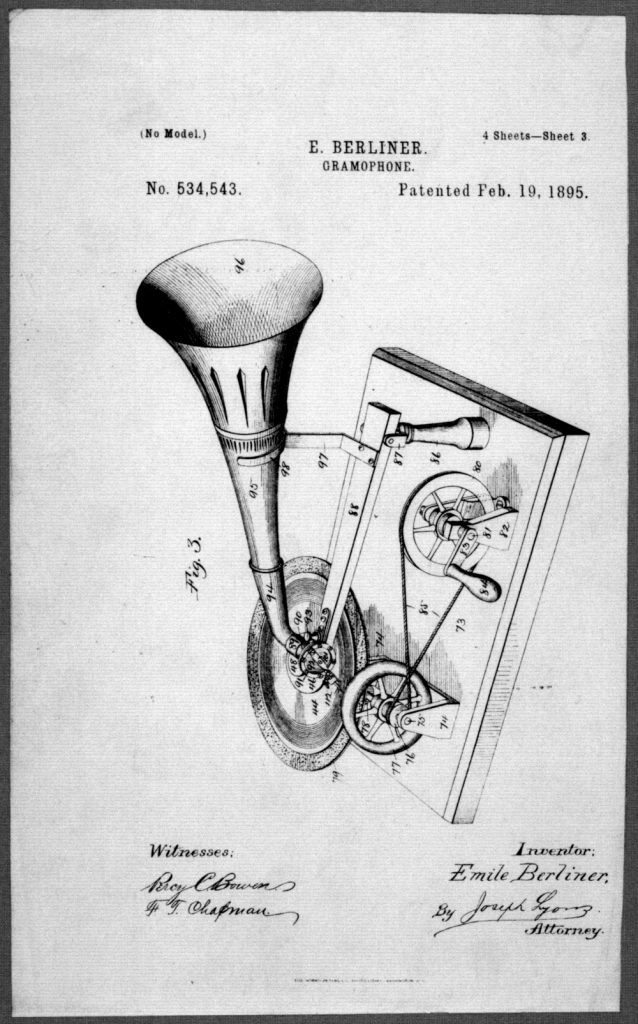

Invention Of The Gramophone

Berliner entered the fray not with the intent of imitating the devices then in vogue, but by creating a recording system that would correct the defects of the prior extant instruments. With this principle in mind, Berliner set out to invent new recording materials, develop entirely new principles of recording and produce new instruments that would be capable of the accurate playback of musical sounds.

Berliner concluded that a flat disc would be much easier to “cut” and subsequently impress than the then-extant cylinder-type playback rolls. This process had the commercial advantage of being relatively inexpensive to duplicate in quantity by pressing the recordings on a “master” disc.

He concluded that a flat disc would be much easier to “cut” and subsequently impress than the then-extant cylinder-type playback rolls. After considerable experimentation with materials, including celluloid and hardened rubber, he eventually settled on a hardened shellac disc. With this material, the cut was made on a zinc platter with a waxed surface, then immersed in an acid bath to produce a “master.” This process resulted in a metal reverse, or negative, whose grooves would project outward instead of inward. The zinc negative could then be used to press out shellac disc positives. This process had the commercial advantage of being relatively inexpensive to duplicate in quantity by pressing the recordings on a “master” disc.

Another innovation was the process of incising the records laterally (side-to-side) rather than in the then-prevalent vertical (hill and dale) approach. This entirely new approach to recording was branded as a “Gramophon” and was subsequently patented in both the US and Germany. Further improvements included equipping the playback machine with a wind-up, constant-speed spring motor produced by the Eldridge R. Johnson Company of Camden NJ.

The gramophone was displayed for the first time at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia in 1888. Musicians were invited to record on the new zinc master plates, and in 1890, the prestigious publication Scientific American wrote an article with illustrations of these new disc-cutter and playback instruments.

Cylinder Vs. Disc Recording

The gramophone disc and machine had a number of attributes that ensured their quick acceptance. Until Berliner’s inventions, all records were cylinders designed to be played on cylinder machines. These cylinders were made of wax compounds, and they were easily broken and easily worn out. They could not be duplicated in a mass-production sense and could be copied in limited numbers only by mechanical or pantographic means. The vertical-cutting process required that the machines have a feed screw attachment to keep the reproducer and stylus from jumping out of the grooves, and the feed screw could come out of adjustment easily. Storage of cylinders also presented a problem. Because of their dimensions and fragile nature, they had to be stored in box containers. The title of a selection and performer’s name could not be inscribed on the cylinders, so paper slips were inserted in the storage boxes, and these were lost easily.

By contrast, the disc record was made of hard rubber (later shellac) that was less prone to breakage. Discs had a constant deep groove with lateral recording images that eliminated the troublesome feed screw and alleviated the “jumping-out-of-the-groove” problem. Moreover, the flat discs required no storage boxes, they could be mass-produced, and there was a center blank area for inscribing the title of the selection and the artist’s name.

Berliner’s International Gramophone Business

With an initial capitalization of $25,000, the Berliner Gramophone Company was established in Philadelphia PA in 1893. This was followed by the opening of the Berliner Gram-O-Phone Company in Montreal, Canada, in 1897, along with Deutsche Gramaphon Gesellshaft and Britain’s Gramophone Co., Ltd (now EMI) in 1898.

Seaman’s National Gramophone negotiated a contract to produce and market the Edison-controlled Zonophone and Columbia Phonographs, and filed an injunction against Berliner that precluded Berliner from selling his gramophone in the United States. Berliner retaliated by moving his operations to Montreal in 1900, and subsequently developed a major business from Canadian recording studios and manufacturing facilities.

The US firm had engaged Frank Seaman of New York City to handle the marketing and advertising for the US distribution. In what Berliner considered as an underhanded breach of confidence, Seaman’s National Gramophone negotiated a contract to produce and market the Edison-controlled competitive Zonophone and Columbia Phonographs, and filed an injunction against Berliner that precluded Berliner from selling his gramophone in the United States.

Berliner retaliated by moving his operations to Montreal in 1900, and subsequently developed a major business from Canadian recording studios and manufacturing facilities. From 1900 through 1921, the Montreal facilities grew into a complex of more than 50,000 square feet that progressed from records cut on one side only into dual-sided discs introduced in 190814. The company also adopted the “Nipper” image as a trademark.15,16

RCA Victor & The Victrola

Also, in a counter move, Berliner (and his United States Gramophone Company) negotiated an arrangement with Eldridge R. Johnson’s Victor Company (of spring-wound, constant-speed motor fame) to produce gramophones in the United States. These US-produced machines were branded as Victrolas. The Victor Company also started releasing Montreal-produced “Red Seal” 78rpm discs with four-minute playing time for $1.00 each, featuring eminent artists such as Enrico Caruso, Dame Nellie Melba and baritone Mattia Battistini.17

Berliner negotiated an arrangement with Eldridge R. Johnson’s Victor Company to produce gramophones in the United States. These US-produced machines were branded as Victrolas. In 1924, the Berliner interests were bought by the Victor Talking Machine Company, which subsequently was merged in 1929 with RCA, thus becoming RCA Victor.

In 1924, the Berliner interests were bought by the Victor Talking Machine Company, which subsequently was merged in 1929 with RCA, thus becoming RCA Victor. The trademarks “Nipper” and “His Master’s Voice” were inherited by each succeeding company and have become trademarks recognized around the world.

For many years, the term “phonograph” was used to denote a cylinder-playing-type machine while “gramophone” described the flat disc player introduced by Berliner. After World War II, the term “gramophone” gradually disappeared from the US language. However, the word lives on in part via the recording industry’s Grammy awards that are issued annually to denote excellence in recordings.

Berliner’s Legacy

The legacy of Emile Berliner, as it pertains to the audio industry, is the record industry that existed from 1894 up to the advent of the stereo LP. Berliner’s lateral-cut flat disc doomed the vertical-cut cylinder, although Thomas Edison refused to throw in the towel until 1929. Berliner’s disc was not to be superseded for 60 years. Certainly, manufacturing techniques were improved, zinc was replaced by wax for mastering, the speed of revolution that varied in the early years finally settled down to 78rpm, and 1925 saw the introduction of electrical recording processes (see “Georg Neumann: Microphone Pioneer”). But until the stereo LP, which employed Berliner’s lateral cut combined with the cylinder’s vertical cut, there was no basic change to that which Berliner had brought to market in 1894.18

Berliner’s lateral-cut flat disc doomed the vertical-cut cylinder, although Edison refused to throw in the towel until 1929. Berliner’s disc was not to be superseded for 60 years.

If for no other reason than his contributions to the sound industry, Berliner should be a remembered name. However, other accomplishments from this remarkable individual bear mention:

- Parquet carpet, used as a floor covering, was patented by Berliner in 1899.

- Acoustical tile as a medium to control acoustical response in public spaces was the subject of a 1926 Berliner patent.

- The helicopter and lightweight internal combustion engines were developed by Berliner (1906-07). His development in this area included the construction and patents for a lightweight internal combustion engine for powering the rotors of his helicopter—work that his son Henry continued.

- In the field of public health, he contributed significantly toward the establishment of tuberculosis sanitariums and inaugurated the Bureau of Health Education to promote public hygiene and health education for mothers and children. He tirelessly campaigned for increased awareness for the need for the distribution of cleaner milk in an effort to reduce mortality rates of young babies and children.

- An avid Zionist, Berliner embraced the cause for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and authored a number of papers supporting Zionism.

Berliner’s Death

Prior to his death, Berliner dictated a letter to his wife in which he expressed both his humanitarian and patriotic feelings: “When I go I do not want an expensive funeral. Elaborate funerals are almost a criminal waste of money. I should like Alice [his daughter] to play the first part of the ‘Moonlight Sonata’ and at the close maybe Josephine will play Chopin’s ‘Funeral March.’ Give some money to some poor mothers with babies and bury me about sunset. I am grateful for having lived in the United States and I say to my children and grandchildren that peace of mind is what they should strive for.”

Emile Berliner died of a heart attack on August 3, 1929 at the age of 79.

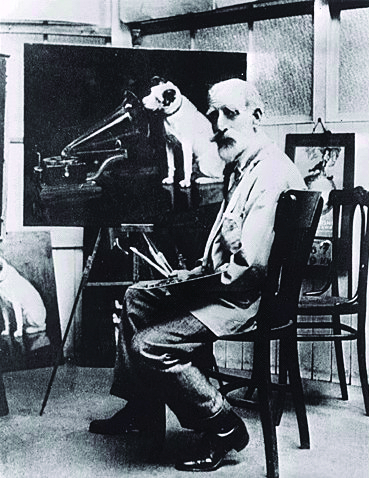

Sidebar: The Nipper Tale

Nipper the dog was born in Bristol, England, in 1884 and was so named because of his tendency to nip the backs of visitors’ legs. Nipper was part bull terrier with a trace of fox terrier. The brother of Nipper’s master, the artist Francis Barraud, painted Nipper listening to a phonograph, and registered it on February 11, 1899, as “Dog looking at and listening to a Phonograph.” Barraud tried to sell the painting to the Edison Company without success. “Dogs don’t listen to phonographs,” the company said.

In an article for Strand Magazine, Barraud wrote that he next visited the English Gramophone Company Ltd., whose manager, Barry Owen, offered to buy the painting if the cylinder-playing device in the painting could be repainted with a disc-playing machine. Barraud was paid £100 for the painting and copyright. In January 1900, the painting made its public appearance in the Gramophone Company’s advertisements. Nipper listening to a gramophone was registered as the company’s trademark on July 16, 1900. Nipper first appeared on the back of Berliner record No. 402 with Frank Bata singing “Hello My Baby.”

Francis Barraud spent much of the rest of his working life painting 24 replicas of his original, as commissioned by the Gramophone Company. In 1907, the illustration was captioned “His Master’s Voice” and was so registered as a trademark in 1910.

References

- After emigrating to the US, Emil Berliner de-Prussianized and anglicized the spelling of his given name of Emil to Emile; one may also encounter the Gaelic spelling as Èmile. We are using the anglicized form here.

- Kurinsky, Samuel, Emile Berliner; An Unheralded Genius, Part 1—The Early Years; fact paper 27-I, Hebrew History Federation Ltd., www.hebrewhistory.info/factpapers/fp027-1_berliner.htm

- Shultz, Peter, The Berliners—A Jewish Family in Hanover (1773-1943), http://home.att.net/~Berliner-Ultrasonics/berlhann.html [Editor’s note: Link no longer active.]

- Das Museum Phonographen Gram-mophone, www.phonograph.com/deutsch/bio-berl.htm [Editor’s note: Link no longer active.]

- Wile, F.W., Emile Berliner, Maker of the Microphone, Bobbs Merrill Company, 1926. (Long out of print; Berliner’s grandson, Oliver, noted that the book did not sell well and the publisher offered the remaining volumes to the Berliner family at cost—an offer they refused.)

- Wile, Ibid.

- Four months later, on July 21,1877, Thomas Alva Edison applied for a patent on a similar device.

- The Library of Congress; http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/berlhtml/berlhome.html

- Wile, Ibid.

- 10. Documents in The German Phono Museum state that Berliner received $75,000.

- Kaufman, Herbert, in a Washington newspaper obituary about Berliner dated August 12, 1929, stated that “The terms included a block of stock, but the young man held out for a life tenure salary of $15,000/year.”—a deal that the writer described as “an experience that did short-change him out of a whaling bunch of cash.”

- Shultz, Ibid.

- Stefan Jones, SeJ@aol.com who took his facts from Roland Galled, The Fabulous Phonograph, J.P. Lippincott, NY, 1955.

- The first artist to appear on a dual-sided disc was Joseph Saucier (1869-1941), singing “La Marseillaise.”

- Musée des Ondes Berliner, Montréal, Canada, La Berliner Gramophone: www.contact.net/berliner/biogrfr.html [Editor’s note: Link no longer active.]

- The Nipper Saga, www.cedmagic.com/home/nipperscape/nipper.html

- Schoenherr, Steven, Recording Technology History, www.regencytr1.com/images/Recording%20Technology%20History.pdf

- The Library of Congress, www.memory.loc.gov/ammem/berlhtml/berlemil.html

This article was originally published in the November 2004 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.