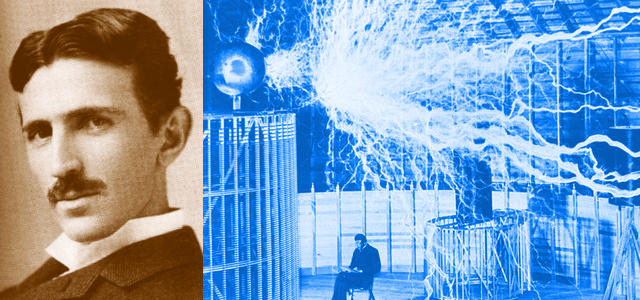

Stories abound about the accomplishments and apparent eccentricities of Nikola Tesla, the turn-of-the-century Croatian-born inventor who—almost single-handedly—transformed electrical distribution throughout the world. The 1880s and 1890s were times of giddy, progressive advances in communication technology. Improvements in telephone technology heralded a promise that voice (and ensuing electronic) communications would soon become the universal method of conveying information and emotions. Electrical power distribution would, within 25 years, convert a gas-lit and kerosene-dependent consumer into a “flip-the-switch” electrical customer.

The Early Years

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) was born in Smiljan Lika, Croatia, the son of a domineering, paternalistic Serbian Orthodox clergyman and an overburdened mother of several siblings. Despite the efforts of his father to steer him into entering the clergy, Nikola obstinately gravitated to more scientific matters. In this pursuit, he took up engineering studies at Joanneum Polytechnical in Graz and later the University of Prague. These studies did not enhance his relationship with his family, but did ingrain in him a strong sense of logical engineering.

According to his sympathetic biographer Margaret Cheney1, Tesla was a talented student who quickly excelled in languages while he was still in what we would consider elementary school. Tesla became fluent in not only the Slavic dialects, but also in German, French, Italian and English. Moreover, at an early age, he took a strong interest in both mathematics and physics. Nevertheless, his strong-willed father continued to insist that the youngest Tesla was destined for the clergy. It was only after several serious illnesses that Nikola was able to convince his father that his life depended on the pursuit of an engineering career2.

Despite the efforts of his father to steer him into entering the clergy, Nikola obstinately gravitated to more scientific matters.

Given his quick wit in the understanding of physics and an ability to visualize concepts, Tesla began to conceive of matters and mechanics that had baffled countless previous theorists. As a junior electrical engineer with the Budapest electrical power company, it is related3 that, with a friend observing, he drew in the dirt, with a stick, his concept of an AC generator that did not rely on the then-universally-employed commutators used in DC dynamos. The details of the design had been worked out in his head, and little reference is available regarding how he reached his conclusions. (Tesla was notorious for not adequately documenting his experiments—a quirk that would later draw critics to question his authenticity and the validity of his claims4,5.)

The Edison Recruitment

At this point, Tesla’s history gets a little fuzzy. Depending on what accounts one might read, it would appear that Tesla took a position with the Austrian National Telephone Company after an apparent similar stint with a similar French concern—or vice-versa. Ultimately, he wound up working as an engineer for the French Edison Electrical Power subsidiary; where he was recruited—or at least urged—by Charles Batchelor, Edison’s European agent, to emigrate to the US to join Edison’s research team. So, it was in 1884 that the 34-year-old Serb found himself on the inhospitable sidewalks of New York, virtually penniless—he had exhausted his assets to secure passage to the US and relocation compensation was not yet in vogue—but with a glowing letter of recommendation from Batchelor.

Bear in mind that, in 1884, electricians were few and far between. This was a totally new technology and there were few graduate schools, let alone vocational or technical institutes that concerned themselves with any studies of electricity. Hence, knowledgeable mechanics were scarce.

Little is said about how Tesla navigated his way from the docks to the Edison office’s Fifth Avenue location, but he showed up during a period of major panic for the Edison Electric Light Company. An important east-side power station had sustained a major power outage, and making matters worse, a promised dynamo for the S.S. Oregon’s lighting system was still malfunctioning, seriously delaying its sailing. Tesla was hired on the spot and dispatched immediately to correct the problems aboard the S.S. Oregon.

Edison was a curmudgeonistic, cantankerous individual who viewed physicists with disdain and considered mathematicians as poor providers to industrial pursuits; hence his apparent dislike of Tesla.

By the dawn of the following morning, Tesla had repaired the problems and was on his way back to the Edison plant. He encountered his new employer, who commented somewhat derisively, “I see our young Parisian has spent the night on the town.” To which Tesla replied, “The problem is corrected.”

Edison was a curmudgeonistic, cantankerous individual who viewed physicists with disdain and considered mathematicians as poor providers to industrial pursuits; hence his apparent dislike of Tesla. He was said to have commented contemptuously that “he didn’t need to be a mathematician because he could hire them.” He also commented that his major concern was how he could tell the importance of one of his inventions by the number of dollars it brought and that nothing else concerned him. He may be a folk hero in American history, but his personal attributes and suspect business exploits certainly are open to question6.

The AC/DC Battle

Almost from the start, the confrontation between the two men was an acknowledged fact. Tesla was convinced that AC (alternating current) power distribution was the most practical and efficient means of electrical distribution. Edison, his new employer, was equally stubbornly committed to the concept that DC (direct current) transmission was the wave of the future. According to recorded transcripts, Edison halted his initial interview with Tesla by angrily declaring, related to a discussion of AC power, “Hold up! Spare me this nonsense. It’s dangerous. We’re set up for direct current in America. People like it, and it’s all I’ll ever fool with.” Thus, the battle lines were drawn.

Tesla was convinced that AC power distribution was the most practical and efficient means of electrical distribution. Edison, his new employer, was equally stubbornly committed to DC.

Tesla accepted the challenge to improve Edison’s DC dynamos with the promise of a $50,000 bonus—a lot amount of money in 1886!—if his efforts proved successful. Tesla retired to his workspace and six months later emerged with precisely what Edison was attempting to achieve. Edison reviewed his accomplishments, and when Tesla asked for his money, the so-called Wizard of Menlo Park laughingly commented, “You Parisians don’t appreciate our American jokes.” Edison refused to pay the promised bonus. In response to the refute, Tesla doffed his hat, strode out of Edison’s New Jersey laboratories and offered his services to George Westinghouse.

For the next 20 years, Edison and Westinghouse were combatants in the direction of power distribution in North America. The contest often was acrimonious and fraught with misalignments and fraudulent claims on the part of both parties. Teams of lawyers polished the rails between Westinghouse’s Pittsburgh headquarters and Edison’s corporate enclave in New York to pursue lawsuits for infringements and patent violations.

Edison, in an act of subterfuge carried out through an intermediary, purportedly acquired a Westinghouse AC generator under the guise of delivering it to the Buenos Aires, Argentina, subway system. In fact, he intended to donate that unit to the New York State Penitentiary System as an example of the lethal consequences of how AC could potentially kill those who might employ this type of distribution.

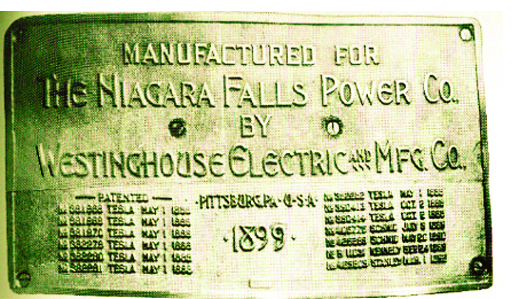

Meanwhile, Tesla rose in stature in the Westinghouse Engineering Group, working on improving AC motors and generator sets. The result of Tesla’s incredible talents is that we enjoy the benefits of the poly-phase motors that drive our modern electrically oriented world.

When Westinghouse AC equipment was chosen in 1899 for the new Niagara Falls power plant, Edison’s dream of a DC world collapsed.

RF Transmission Principles

Tesla steadfastly held to the opinion that, not only communications signaling, but also AC power distribution, could be accomplished via RF transmission principles. If his theorizing had been used, the unsightly and inefficient high-voltage power-transmission facilities that line our byways and urban landscapes might have well been avoided.

However, the industrial barons of the time had economic interests in maintaining control of their investments in the generating and distribution networks for electrical power transmission. Consequently, Tesla’s humanitarian concept of providing “free” power and information to homes via RF magnifying transmitters clearly flew in the face of industrialists and financiers such as Westinghouse, Edison and J.P. Morgan.

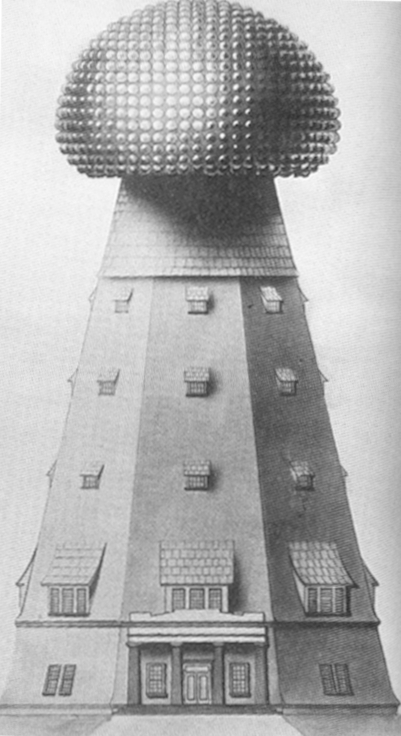

Tesla also had a noted feud with Italian radio transmission pioneer Guglielmo Marconi. Tesla attacked Marconi by announcing plans to construct and equip a world communications center that he named Wardenclyffe, which would compete with Marconi’s wireless telegraph system. Also known as the Tesla Tower, Wardenclyffe was a transmitter station that would not merely transmit Morse signals to Europe, but would become a true telecommunications enterprise. As Tesla envisioned the facility, it would operate more efficiently than the combined forces of today’s radio, television, wire service, lighting, telephone and power systems7.

To secure the necessary financing for Wardenclyffe, Tesla had approached J.P Morgan. Again, through yet another piece of financial chicanery, Morgan strung him along and then abruptly yanked the rug out, denying Tesla the funding necessary for expansion. The partially finished facility was eventually abandoned, and the Long Island property reverted to the potato farm from whence it had sprung.

In a long, drawn-out patent case brought against Marconi and the Marconi Wireless Company, Tesla claimed his patents for radio transmission predated Marconi by at least five years. This case dragged through the courts from 1907 until 1944, when Tesla was finally vindicated as the inventor of radio by the US Supreme Court. It was a bittersweet reward inasmuch as Tesla had died ten months earlier in 1943.

Tesla claimed his patents for radio transmission predated Marconi by at least five years. This case dragged through the courts from 1907 until 1944, when Tesla was finally vindicated as the inventor of radio by the US Supreme Court.

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail all of the intrigues and ensuing legal battles that swirled about Tesla’s world. However, suffice to say that Tesla was a rather naive individual, a poor businessman and lacked the necessary funds to wage legal warfare with his much-better-heeled combatants. Constantly cheated by his business associates, he watched as other less-talented exploiters laid claim to his inventions until, in the end, he died alone and penniless in a New York hotel room.

A Controversial Visionary

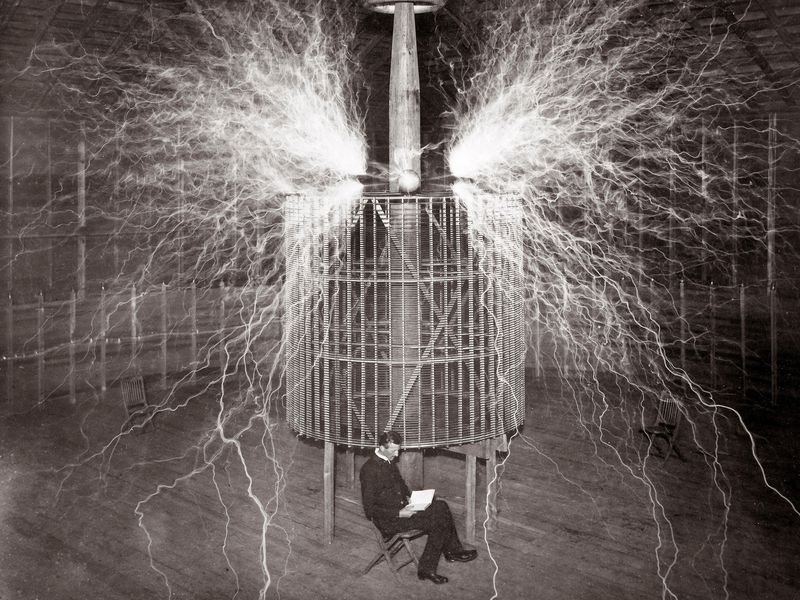

Tesla’s development of what to this day are referred to as Tesla Coils laid the foundation for subsequent development of both power and communication transformer design. His work on robotics and remote-control vehicles, plasma and laser guns predated their actual development by 90 years. And, in some cases, his predictions are still the gist of continuing development as we enter the 21st Century. He also attacked Einstein’s Theory of Relativity by introducing his concept of The Dynamic Theory of Gravity. It wasn’t until 1980 that science proved that we have sufficient knowledge to realize Tesla was right.

It became vogue to dismiss [Tesla] as an eccentric old man whose far-fetched ideas were beyond the realm of reason.

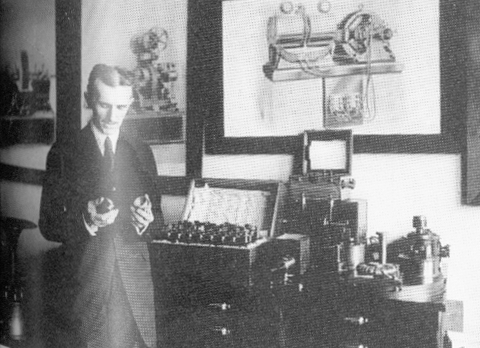

A dapper, flamboyant individual and somewhat of a publicity hound, Tesla expressed his concepts in magazine articles frequently and in public demonstrations, which infuriated the scientific community. Much of his writing was dismissed as pure science fiction at the time. Tesla’s own actions sometimes did little to help his reputation. In a press statement issued in the 1930s, he proclaimed, “I have devoted much of my time…to the perfecting of a new small and compact apparatus by which energy in considerable amounts can now be flashed through interstellar space to any distance without the slightest dispersion and thereby allow interplanetary communications.”8 Tesla continued that he would be submitting his documentation for consideration by the Institute of France in pursuit of the Pierre Guzinan Prize. He never explained the work, and he didn’t receive the prize. Such actions did not endear him to his scientific colleagues, and it became vogue to dismiss him as an eccentric old man whose far-fetched ideas were beyond the realm of reason.

Later, with the outbreak of hostilities in Europe and subsequent US involvement in World War II in 1941, Tesla contacted the US War Department to share the discovery of his “teleforce,” a system that the popular press had dubbed Tesla’s “Death Ray.” The US military dismissed him as a crackpot. However, this action was to have dire circumstances on the occasion of Tesla’s death. Acting in the hysteria of wartime, and within days after he had died, the US authorities swooped in to confiscate Tesla’s writings and materials. Many of these artifacts are now just starting to see the light of day, having been kept under wraps in the name of national security for the best part of 60 years.

As you sit before your computer, scanning the internet under fluorescent electric lights, cooled by air generated by an AC induction motor and listening to your radio—all powered from an electric power grid—you are reaping the benefits of Nikola Tesla’s genius.

With the use of his name to describe the unit of magnetism, Tesla joins Volta, Ampere, Gilbert, Henry, Ohm and Faraday in the same distinguished hall of fame. However, other than a small plaque on a signpost behind the NYC Public Library designating the small plaza as Tesla Square, where he frequently went to feed his beloved pigeons, there is scant testimony to the contributions he made to his adopted country. The Tesla Museum in Belgrade houses the remnants of his works and writings.

But, as you sit before your computer, scanning the internet under fluorescent electric lights, cooled by air generated by an AC induction motor and listening to your radio—all powered from an electric power grid—you are reaping the benefits of Nikola Tesla’s genius.

1 Cheney, Margaret, Tesla – Man Out of Time, Dorset Press, NYC 1981; ISBN 0-88029-419-1

2 Seifer, Marc J., The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla; Citadel Press, Secaucus NJ 1999. Is a later work and introduces materials probably not available to Margaret Cheney; both are recommended.

3 Cheney, ibid.

4 Martin, Thomas Commerford, The Inventions, Researches & Writings of Nikola Tesla, Barnes & Noble, NYC, 1992; ISBN 0-88029-8120-X

5 Tesla, Nikola and Childress, David H. The Fantastic Inventions of Nikola Tesla, Adventures Unlimited Press, Kempton IL, 1993; ISBN 0-932813-19.4

6 Edison was at one point in time both the Chief Engineer for Postal Telegraph and a member of the Board of Directors for Western Union. Was that a conflict of interest?

7 Seifer, Marc J., ibid.

8 The Man Who Invented the Twentieth Century: Nikola Tesla, Forgotten Genius of Electricity, Lomas, Robert Dr. Headline Press, 1999

This article was originally published in the November 2002 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.