As the life of radio pioneer Edwin Howard Armstrong proves, the history of advancements in radio technology is rife with intellectual property theft, backstabbing and personal tragedy. Some of the great minds who made major contributions to radio broadcasting received little recognition in their lifetimes, and their accomplishments were often claimed by their more well-heeled contemporaries who had the money to invest in drawn-out legal battles over intellectual property rights.

Fully five years before Guglielmo Marconi purportedly made history with a transmission of the Morse character “s” (…) between England and North America, the Croatian inventor Nikola Tesla had laid claim to the principles for RF (radio frequency) transmission. Much akin to the exploitation by Samuel Morse of Joseph Henry’s initial explorations of electromagnetism some 50 years prior, Marconi expropriated the ideas of Tesla and Heinrich Hertz, and without due credit, claimed exclusive rights to the invention of wireless radio.

The history of advancements in radio technology is rife with intellectual property theft, backstabbing and personal tragedy.

Tesla was not a particularly litigious individual; however, he took umbrage at Marconi’s assertion that Marconi had fostered wireless transmission. Tesla sued on the basis of patent infringement. Tesla’s suit was filed in 1904, and it was 40 years before the US Supreme Court would rule in 1944 that Tesla’s claim for antecedence was valid, and that Tesla could claim the rightful honor for the invention of the principles of RF transmission. The judgment was of little comfort to Tesla, who had died, penniless in a New York hotel room, some 10 months prior to the court’s decision. [For more information about Tesla, read “Nikola Tesla: Visionary or Madman.”]

Marconi: Charlatan & Fraud

Marconi was a charlatan and a fraud. The son of a prominent Italian businessman and a successful, politically connected, Irish/UK mother, he possessed the political and financial wherewithal to trample lesser subjects. He took full advantage of his and his family’s financial and political position to foster the creation of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company.

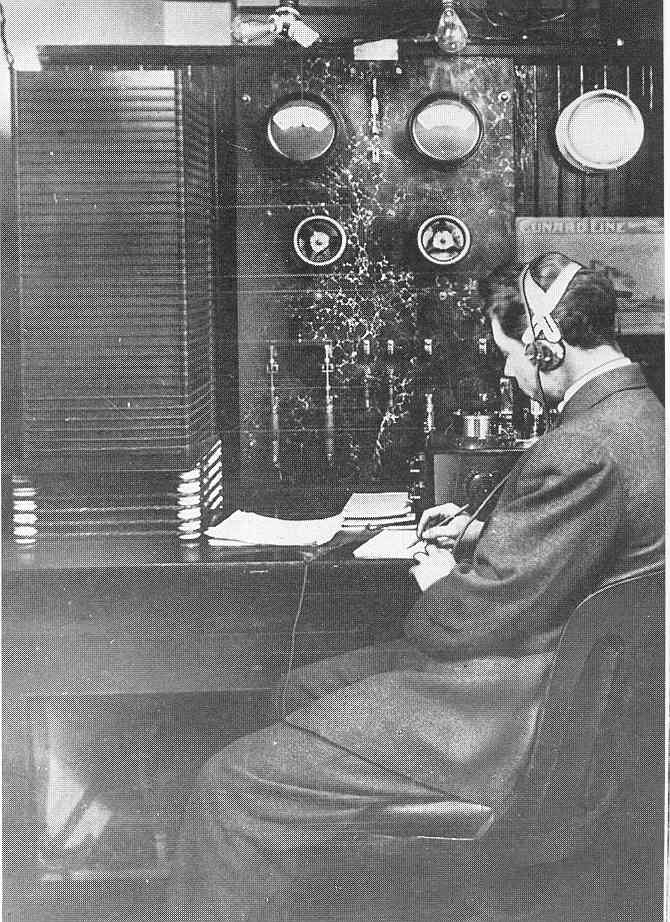

The primary concern in the early days of wireless was the ability to transmit telegraphic code between Europe and North America, and to and from ships on the high seas. Audio amplification was not yet a reality, and wireless transmitters had to rely on the make/break transmissions of spark-gap oscillators. Voice transmission was, obviously, not yet a possibility. Nevertheless, the navies of the world were rather quick to sense the benefit of being able to communicate between their government headquarters and between the individual ships within their fleets. Signal flags and the transmission of light signaling (which dictated that ships remain in visual contact) had been supplanted. The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company (later to be absorbed into the Radio Corporation of America) and the fledgling De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company quickly vied for contracts to equip and staff naval and commercial vessels with telegraphic equipment.

It would take at least two more decades and the tragedy of World War I before radio would become anything other than a wireless telegraphic communication system.

Given the limitations of early radio, it can be understood that this new medium was envisioned simply as a communication vehicle, and the concept of broadcasting as we now know it was barely even considered. Indeed, given the stage of development of the equipment available the time, broadcasting of audible intelligibility was totally inconceivable. It would take at least two more decades and the tragedy of World War I before radio would become anything other than a wireless telegraphic communication system.

Sarnoff-Marconi Legend

Intertwined in the rise of the American branch of the Marconi Company was a young man who, in 1900, emigrated from Russia to the United States with his mother and several siblings to be reunited with their impoverished father in New York City. David Sarnoff, who would eventually rise to become the Napoleonic head of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), joined the Marconi Company as a messenger boy. He swiftly learned to telegraph and came to the notice of Marconi himself. The young Sarnoff’s advancement was quite rapid, and he soon found himself manning important posts both aboard Marconi-equipped ships and at land-based stations.

At that point, reality seems to have slipped away, and a legend was created. Sarnoff’s often embellished story of being the sole telegrapher who heard the news and transcribed the details of the RMS Titanic disaster fueled the fire for extravagant claims of personal dedication. As Tom Lewis reported1, “It is unlikely that Sarnoff was on duty at the time of the [Titanic’s] sinking, and the station he was reputedly manning was probably closed during the period of time in which he claimed responsibility for performing his heroic efforts.” Nonetheless, the oft-repeated tale fostered Sarnoff’s heroic image and subsequently assisted in escalating Sarnoff into the position as the stalwart leader of RCA.

De Forest & the Audion

Lee De Forest is generally recognized as the inventor of the triode tube. Borrowing rather freely from British inventor Sir John Ambrose Fleming, De Forest incorporated (expropriated) Fleming’s earlier works in vacuum-tube technology. De Forest claimed rights to the development of the “audion” three-element vacuum tube. At a time when patent litigation and countersuits seemed rampant, one of the principal protagonists was De Forest, a nasty little man and a prolific inventor who filed patents often with wide-ranging implications and filed suits in an often acrimonious fashion.

De Forest apparently recognized that the introduction of a “grid” into Fleming’s diode was capable of producing amplification; however, he seemed totally incapable of explaining or documenting the process.

In the tinker-tryer climate of the times, De Forest apparently recognized that the introduction of a “grid” into Fleming’s diode was capable of producing amplification; however, he seemed totally incapable of explaining or documenting the process. As Lewis commented2: “Now he [De Forest] could regulate the flow of electrons from the filament to the plate and amplify them. Precisely how the filament, grid and plate worked, he was not sure. The theories he did propose about their action were in fact incorrect. But the sounds coming from his earphones showed that his audio amplifier did work. With the simple addition of the grid to Fleming’s tube (valve), modern electronics was born.”

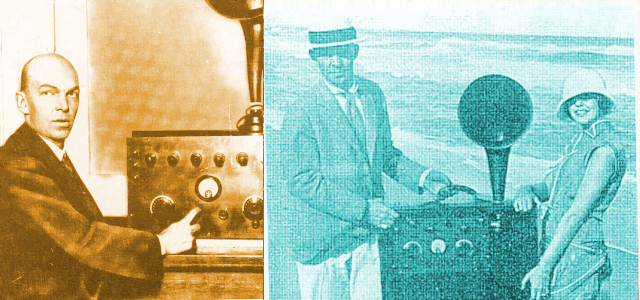

Armstrong’s Advancements

Edwin Howard Armstrong (1890-1954) was a mere 13 years old when De Forest enthusiastically displayed the exploits of the De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company, the newly formed, boldly proclaimed, fraudulently capitalized, telegraphic firm that bore his name at the Saint Louis Exposition in 19043. Intrigued by the advancement in wireless technology, the young Armstrong delved into the technology of the then-possible emerging opportunities in radio. Reading widely and experimenting in his parents’ residence in Yonkers NY, the young Armstrong soon gained proficiency in RF circuit development.

While still a student at New York Columbia University, Armstrong came to the realization that, by employing regenerative feedback, the amplification of De Forest’s audion could be significantly enhanced.

While still a student at New York Columbia University, Armstrong came to the realization that, by employing regenerative feedback, the amplification of De Forest’s audion could be significantly enhanced. Indeed, his experiments showed that the amplification of an audio signal could be magnified by the order of some 20,000:1. Consequently, what previously could be heard faintly over a set of earphones could now be heard across the room from a loudspeaker.

Armstrong’s exploits and advancements in electronic theory drew some serious attention, and thus ensured that he would be served with a patent infringement suit by De Forest. This absurd claim for preeminence on the part of De Forest, who could barely explain the operation of his audion, poorly concealed his claims for the invention of negative feedback regeneration. Despite a series of judgments by lower courts that had ruled in Armstrong’s favor, after 14 years of judicial wrangling, the US Supreme Court, with the acquiescence of a misguided or misinformed justice, ruled in De Forest’s favor.

Armstrong’s exploits and advancements in electronic theory drew some serious attention, and thus ensured that he would be served with a patent infringement suit by De Forest.

The scientific community was appalled and staunchly supported Armstrong. In fact, the Institute of Radio Engineers steadfastly refused to revoke the earlier-awarded gold medal delivered to Armstrong in honor of his work in developing the regenerative circuitry. De Forest might have won this legal battle, but his esteem on the behalf of his colleagues was badly diminished. De Forest thus earned the title of “that nasty little man,” an epithet that haunted him to his grave.

Superheterodyne

Meanwhile, Armstrong continued to perfect radio-receiver and transmitter technology. Realizing that, at a given point, the regenerative circuit could be forced into an oscillation form, he fostered an RF transmission mode that would supplant the previous 20 tons of mechanical devices required for spark-gap oscillation transmissions.

The introduction of IF (intermediate frequency) circuits brought forth the superheterodyne receiver. This vastly simplified the tuning of radio receivers and transmitters and opened the way for commercial production of consumer-oriented broadcast receivers.

The introduction of IF (intermediate frequency) circuits brought forth the superheterodyne receiver. This vastly simplified the tuning of radio receivers and transmitters and opened the way for commercial production of consumer-oriented broadcast receivers. Sarnoff, who by 1916 was a top official at RCA, was to suggest in an internal memo that the company should consider the manufacture of a “Radio Music Box.” He wrote4: “I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a ‘household utility’ in the same sense as the piano or phonograph. The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless…. The radio can be designed in the form of a simple ‘Radio Music Box’ and arranged for several different wavelengths, which should be changeable with the throwing of a single switch or pressing of a single button.”

Hence, with Armstrong’s advancements in circuitry and Sarnoff’s vision, attention was turned to the possibility of widespread public transmission of audible materials and subsequent consumer consumption.

The War Years

During a stint as a Major in the US Signal Corp during World War I, Armstrong almost singlehandedly outfitted allied aircraft with radio communications—a feat that drew accolades from the US and other allied forces.

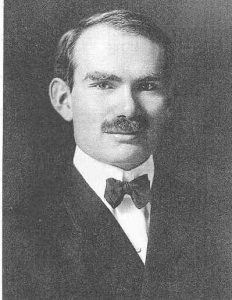

After his service on the Western Front, he returned to the commercial sector and quickly made acquaintance with Sarnoff, ultimately marrying Sarnoff’s personal secretary, Marion. From that point in 1923, Mrs. Marion Armstrong was to be her husband’s stalwart companion until the pressures of commerce forced their separation in 1954. After Armstrong’s death by suicide mere months after their split, Marion would pick up the mantle that eventually vindicated her estranged husband’s claims of preeminence in the field of FM (frequency modulation).

In 1920, Armstrong sold his superhetrodyne patent rights to Westinghouse for a significant amount of stock and cash. Westinghouse, in turn, proceeded to put the first AM broadcast station on the air: KDKA in Pittsburgh PA. Largely at the bequest of the US Government, which feared foreign dominance of the fledgling US broadcast industry, the combined patent rights of AT&T, Westinghouse and General Electric were vested in the monopolistic Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Consequently, Armstrong’s patents now became the property of RCA.

In 1920, Armstrong sold his superhetrodyne patent rights to Westinghouse for a significant amount of stock and cash. Westinghouse, in turn, proceeded to put the first AM broadcast station on the air: KDKA in Pittsburgh PA.

Although Armstrong had achieved the status of a millionaire, he maintained his role as an instructor at Columbia University and turned his attention to the reduction of static in broadcasting. These investigations lead him to the exploration of FM (frequency modulation) as an alternative to AM (amplitude modulation) transmission. Several others had examined this concept and dismissed it as unworkable. Despite these earlier prognostications, Armstrong strove ahead and, undaunted, stated in a rather colloquial fashion, “It ain’t ignorance that causes all the trouble in this world. It’s the things people know that ain’t so.”5

The amicable Armstrong/RCA relationship and the strong personal friendship between Armstrong and Sarnoff eventually began to dissolve. During Armstrong’s legal hassle with De Forest, RCA had steadfastly refused to support Armstrong’s position. Somewhat cynically, the corporation’s attorneys reached the conclusion that, if De Forest won the lawsuit, it would extend their patent rights for an additional 10 years, with no need to further compensate Armstrong.

By 1934, the consumer radio industry, even in the depths of a major depression, had reached proportions of $2 billion. The major radio receiver manufacturers, including RCA, rushed product to the market using Armstrong’s regenerative and super-regenerative circuits, with scarcely any consideration of any monetary compensation to its inventor.

Armstrong’s investigations lead him to the exploration of FM (frequency modulation) as an alternative to AM (amplitude modulation) transmission. His efforts in the development of FM further deteriorated his relationship with RCA.

Armstrong’s efforts in the development of FM further deteriorated his relationship with RCA. After some successful experiments in the transmission of FM signals in 1934, RCA’s Sarnoff later commented, “I thought Armstrong would invent some kind of filter to remove static from AM radio….I didn’t think he’d start up a whole damn new industry to compete with RCA.”

Now essentially disassociated from RCA, Armstrong started dipping into his personal funds and his RCA/Zenith stock to continue his FM exploits. In 1936, he put FM radio W2XMNF on the air from the palisades of Alpine NY. Whereas AM was capable of transmitting up to a maximum of 5KHz, FM could now provide an audible signal from 50 to 15,000 cycles. High fidelity in radio broadcasting was now a reality.

RCA trained its legal and lobbying activities to circumvent FM radio. Speaking out of both sides of their mouths, RCA maintained on the one hand that FM was an invention of RCA engineers, and at the same time lobbied the FCC to shift the FM transmission band upward.

The owners of RCA, with its vested interest in NBC (National Broadcasting Corporation), were furious, and fought back with a vengeance. With millions of dollars in its war chest, RCA was much better financed to defeat Armstrong. RCA trained its legal and lobbying activities to circumvent FM radio. Speaking out of both sides of their mouths, RCA maintained on the one hand that FM was an invention of RCA engineers, and at the same time lobbied the FCC to shift the FM transmission band upward from 42-52Mhz—a shift that would instantaneously make existing FM transmitters and the numerous FM receivers obsolete and, in fact, destroy the industry.

Within hours of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Sarnoff telegraphed President Roosevelt that the resources of RCA would be made available to the US defense and war effort. (Not stated was any reference to the implied profits RCA would realize from providing communication equipment to the allied forces.) Denied a commission in World War I due to the anti-Semitic attitude of the time, Sarnoff was anxious to make his mark in this newer conflict. This earned him a commission as a General in the US Army during World War II; the title of General Sarnoff was a badge he wore bombastically.

Armstrong forgave his patent rights for FM communications to the US military without regard to compensation. Hence, US and Allied troops came to rely on FM communications, forging ahead with FM walkie-talkies.

Armstrong, in turn, forgave his patent rights for FM communications to the US military without regard to compensation. Hence, US and Allied troops came to rely on FM communications, forging ahead with FM walkie-talkies. The German and Axis commands were forced to rely on static-prone AM that probably greatly contributed to their communications breakdowns and subsequent military defeat. Allied forces could easily jam the Axis AM communications, whereas the Allied FM was impervious to similar disruptions.

TV Standards Conflict

Sarnoff and RCA were convinced that FM would be the best possible audio transmission for the new television medium. However, how could they implement the system without paying Armstrong his due? Their immediate solution was to start producing receivers using Armstrong’s inventions and paying him nothing.

During a congressional hearing in 1948, Senator Charles W. Tobey of New Hampshire was to comment: “RCA has been doing everything to keep Armstrong down. They did their damnedest to ruin FM. At the same time they were supplying free TV sets to commissioners of the FCC.”6

Sarnoff and RCA were convinced that FM would be the best possible audio transmission for the new television medium. Their immediate solution was to start producing receivers using Armstrong’s inventions and paying him nothing.

In a similar vein, RCA set about to destroy CBS (Columbia Broadcast System) and the much-advanced transmission/reception principles of Conrac’s Fleetwood series of television receivers. RCA had invested vast sums to develop their TV base and was not about to let others obsolete what was essentially an RCA proprietary system. Intense lobbying to Congress and pressure on the FCC proved successful, with the RCA plan becoming the standard for TV operation in the US. CBS and Conrac obviously lost and, along with TV manufacturers, would consequently be faced with paying royalties to RCA.

Armstrong’s Demise

Armstrong had surmised that the static-free, better audio quality of FM would shortly overtake AM in consumer preference. His confidence in the superiority of FM was bolstered when the National Television Standards Committee (NTSC) decided that FM was to be the standard for the audio portion of the TV broadcast signal. He was expecting to reap the rewards of his efforts in the form of royalties on the manufacture of FM receivers, on the sale of TVs and contracts with FM broadcasters. As time dragged on, RCA finally offered Armstrong $1 million for his efforts. As one punster put it, this was akin to a line from an old, B-grade, Western movie where the rich rancher offers his upstart neighbor $1 million for his property and then says, “Do you want me to pay you, or do you want me to pay your widow?”

Armstrong’s confidence in the superiority of FM was bolstered when the National Television Standards Committee (NTSC) decided that FM was to be the standard for the audio portion of the TV broadcast signal.

In 1948, Armstrong turned to the courts, charging open theft and blatant infringement of his patents. RCA unleashed an army of lawyers who, with trickery, procrastination, truth-twisting, evasion and botheration, tied up the case for six years. RCA had time and money on its side; Armstrong had neither. By 1954, Armstrong was at the end of his rope. He offered to settle for $2.4 million; RCA countered by offering him the insulting sum of $200,000.

At wits’ end, Armstrong approached his wife and asked that they dip into their retirement funds to continue the legal battle. Marion objected, and in the ensuing argument, Armstrong struck her on the arm with a fireplace poker. Marion, who had been Armstrong’s wife of nearly 30 years and his soulmate through all the trials and tribulations, fled to her sister’s home in Connecticut. Armstrong spent that Christmas and New Year’s Eve alone and, on January 31, 1954, he wrote a heartrending letter to Marion, put on his coat and hat, and walked out the window of their 13th story New York apartment.

Following Armstrong’s suicide, Sarnoff piously proclaimed to the press, “I did not kill Armstrong.”

For her part, Marion continued to press the issue of Armstrong’s battle with RCA, and Armstrong’s lawyers, working on contingency, finally forced RCA into making a settlement of just over a million dollars—the same amount that Sarnoff had offered Armstrong in 1940. Sarnoff had finally received an answer to the question, “Do you want me to pay you, or your widow?”

References

1 Lewis, Thomas S, Empire of the Air, Harper/Collins Publishing, NYC 1991; ISBN 0-06-018215-6 [out of print]

2 Lewis, ibid

3 Lewis, ibid

4 Sarnoff David, Looking Ahead, McGraw Hill Book Co., 1968 ISBN 23456-HDBP-7543210698

5 www.brainyquote.com/quotes/edwin_armstrong_298980

6 Lewis, ibid

This article was originally published in the December 2002 issue of Sound & Communications.

Click here for more of Sound & Communications’ “Industry Pioneers” series.